COMMER 1500 AUTOMATIC VAN

Page 48

Page 49

Page 50

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A1YONE who wants proof that automatic transmission must become the rule on light delivery vehicles instead of the exception which it is now, should drive one of the van models which now have this feature as an option. This is my main impression after spending a day testing the Commer 1500 with automatic transmission, and the benefits of greatly reduced driving effort were not accomplished by a serious reduction in fuel economy.

Much of the credit for the fact that ease of driving was not accompanied by any unacceptable side effects must go to the Borg-Warner Type 35 automatic gearbox employed by Comma. At no time was there ay feeling that ratio changes were made at the wrong time and this is. one of the most difficult things to accomplish in applying automatic transmission to a commercial vehicle.

The road speed at which upward and downward changes are made is dictated by the position of the accelerator, and because less throttle is needed to give a particular performance when the vehicle is empty than when fully laden, settings are often a compromise between changes at fairly high speeds when empty and fairly low speeds when full. With the Commer the set-up was very good indeed and I never felt that I would have liked to have an overriding manual control.

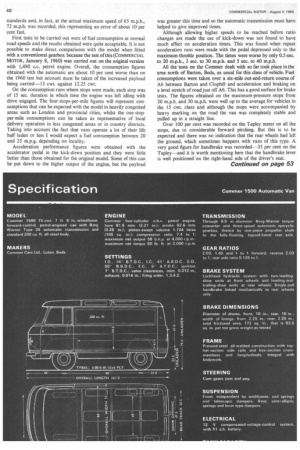

The fitting of automatic transmission was not the only reason why the Commer was a very pleasant vehicle to drive. The driver has as much comfort as in a private car, with controls light and positive, and the suspension was found to be very good indeed. Acceleration tests showed the test vehicle to have a very lively performance and the braking figures obtained were very good.

Commer first introduced the van model from whin the latest design has developed in January, 1960 since when there has been a number of changes in the mechanical specification. There have been two changes of engine—from the original 1,490 c.c. petrol engine to a 1,592 c.c. engine and then in September last year the current 1,725 c.c. petrol was brought in as standard for the 1500 and to its 1-ton capacity counterpart, the 2500.

There is little difference between the 1500 and the 2500 which was introduced in 1962, the only point being that the rear suspension has a greater„ capacity than the 2500 because of the higher weight rating. When the 2500 was introduced stronger front suspension than hitherto was incorporated, but for reasons of standardization this was also applied to the 1500. An important difference in specification so far as this road test is concerned is that automatic transmission is not generally available in the 2500, but only for special and agreed applications.

Outwardly there have been few changes to the model, these being restricted to nine styling operations. With the latest, separate sidelights and flashing indicators were introduced for the front as now required by law. The latest models are called the Series III and at the time of the alterations in September, seating was improved with black instead of red trim.

Petrol and diesel versions Petrol and diesel versions of the 1500 and 2500 are available and in the latter case the Perkins 4.108 engine is employed. This produces 49.5 b.h.p. net at 4,000 r.p.m. and 71 lb. ft. maximum net torque at 2,000 r.p.m. compared with the figures of 58 b.h.p. at 4,000 and 90 lb. ft. at 2,000 r.p.m. for the 1,724 c.c. petrol engine. In the standard version the drive is taken through a four-speed gearbox with synchromesh on all forward gears. The rear axle has hypoid-bevel drive and the 5.125-to-1 ratio as on the test vehicle is standard. A 5.625-to-1 axle ratio is optional and this is recommended for use if the model is to be built as a mobile shop.

There is a difference in the size of brake units between the 1500 and 2500, the standard on the 1500 being 10 in. by 2.25 in. front and 9 in. by 1.75 in. rear, whilst on the 2500 the units are 10 in. by 2.25 in. all round. When automatic transmission is fitted to the 1500 version the brake sizes are the same as the 2500. Another change in the specification with automatic transmission is that a 51 a.h. battery replaces the normal 38 a.h. unit.

A van fitted with the Borg-Warner Type 35 transmission has previously been tested by COMMERCIAL MOTOR and the unit was described in our issue of March 26, 1965. Briefly the Type 35 consists of a 9.5 in.-diameter, three-element torque converter capable of delivering an infinitely variable torque multiplication of between 1 to 1 and 2 to 1. This drives a hydraulically operated transmission gearbox comprising a planetary gear set which provides three forward and one reverse ratio.

In the Commer application the transmission selector lever is mounted on the dash and has five positions: park, neutral, reverse, drive and lock-up. Park locks up the transmission and only when the lever is in this position or in neutral can the engine be started. Reverse is self explanatory and drive is used for normal operation. Selection of lock-up when starting off holds tht bottom ratio up to maximum engine speed and if transferred from drive when on the move either the bottom or intermediate ratio is selected according to the road speed and accelerator-pedal position.

The road speeds at which upward ratio changes are made will vary according to the position of the accelerator pedal, higher speeds being reached in the intermediate ratios with wider throttle openings. In addition there is a "kick-down" position beyond full throttle which gives a further increase in the road speeds before an upward change is made.

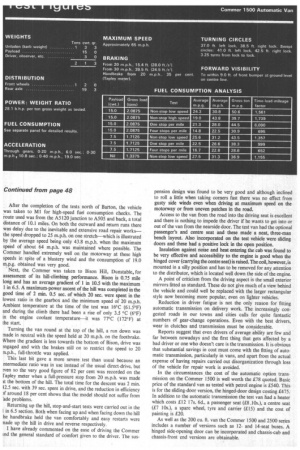

When the test vehicle was fully laden, a change from first to second was made at 20 m.p.h. and from second to third at 30 m.p.h. in the full-throttle position. With kick-down the changes were delayed to 30 m.p.h. from first to second and to 44 m.p.h. from second to third. The speeds quoted take into account a speedometer error of 5 per cent fast at 30 m.p.h. and 7 per cent fast at 40 m.p.h. This was a lot of speedometer error by present-day standards and, in fact, at the actual maximum speed of 65 m.p.h., 72 m.p.h. was recorded, this representing an error of about 10 per cent fast. •

First tests to be carried out were of fuel consumption at normal road speeds and the results obtained were quite acceptable. It is not possible to make direct comparisons with the model when fitted with a conventional gearbox because the test of this (COMMERCIAL MOTOR, January 8, 1960) was carried out on the original version with 1,490 c.c. petrol engine. Overall, the consumption figures obtained with the automatic are about 10 per cent worse than on the 1960 test but account must be taken of the increased payload being carried-15 cwt. against 12.25 cwt.

On the consumption runs where stops were made, each stop was of 15 sec. duration in which time the engine was left idling with drive engaged. The four-stops-per-mile figures will represent consumptions that can be expected with the model in heavily congested areas such as London and provincial cities, whilst the one-stopper-mile consumptions can be taken as representative of local delivery operation in less congested areas or in country districts. Taking into account the fact that vans operate a lot of their life half laden or less I would expect a fuel consumption between 20 and 25 m.p.g. depending on locality.

Acceleration performance figures were obtained with the accelerator pedal in the kick-down position and they were little better than those obtained for the original model. Some of this can be put down to the higher output of the engine, but the payload was greater this time and so the automatic transmission must have helped to give improved times.

Although allowing higher speeds to be reached before ratio changes are made the use of kick-down was not found to have much effect on acceleration times. This was found when repeat acceleration runs were made with the pedal depressed only to the maximum-throttle position. The times were worse by only 0.5 sec. to 20 m.p.h., 3 sec. to 30 m.p.h. and 5 sec. to 40 m.p.h.

All the tests on the Cornmer dealt with so far took place in the area north of Barton, Beds, as usual for this class of vehicle. Fuel consumptions were taken over a six-mile out-and-return course of A6 between Barton and Clophill and acceleration and braking on a level stretch of road just off A6. This has a good surface for brake tests. The figures obtained on the maximum-pressure stops from 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. were well up to the average for vehicles in the 15 cwt. class and although the stops were accompanied by heavy marking on the road the van was completely stable and pulled up in a straight line: Over 100 per cent was recorded on the Tapley meter on all the stops, due to considerable forward pitching. But this is to be expected and there was no indication that the rear wheels had left the ground, which sometimes happens with vans of this type. A very good figure for handbrake was recorded-35 per cent on the Tapley—and it is worth mentioning here that the handbrake lever is well positioned on the right-hand side of the driver's seat.

After the completion of the tests north of Barton, the vehicle was taken to MI for high-speed fuel consumption checks. The route used was from the A.5120 junction to A505 and back, a total distance of 10.1 miles. On both the outward and return runs there was delay due to the inevitable and extensive road repair worksthe speed dropped to 25 m.p.h. on one stretch-which is illustrated by the average speed being only 43.8 m.p.h. when the maximum speed of about 64 m.p.h. was maintained where possible. The Commer handled extremely well on the motorway at these high speeds in spite of a blustery wind and the consumption of 19.0 m.p.g. obtained was very good.

Next, the Commer was taken to Bison Hill, Dunstable, for assessment of its hill-climbing performance. Bison is 0.75 mile long and has an average gradient of 1 in 10.5 with the maximum 1 in 6.5. A maximum-power ascent of the hill was completed in the good time of 2 min. 0.5 sec. of which 20 sec. were spent in the lowest ratio in the gearbox and the minimum speed of 20 m.p.h. Ambient temperature at the time of the test was I6°C (61.5°F) and during the climb there had been a rise of only 3.5 °C (6°F) in the engine coolant temperature-it was 77°C (172°F) at the start.

Turning the van round at the top of the hill, a run down was made in neutral with the speed held at 20 m.p.h. on the footbrake. Where the gradient is less towards the bottom of Bison, drive was mgaged and with the brakes still on to restrict the speed to 20 m.p.h., full-throttle was applied.

This last bit gave a more severe test than usual because an ntermediate ratio was in use instead of the usual direct-drive, but wen so the very good figure of 82 per cent was recorded on the l'apley meter when a full-pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. was made it the bottom of the hill. The total time for the descent was 2 min. 12.5 sec. with 39 sec. spent in drive, and the reduction in efficiency )f around 18 per cent shows that the model should not suffer from 'ade problems.

Returning up the hill, stop-and-start tests were carried out in the in 6.5 section. Both when facing up and when facing down the hill he handbrake held the van comfortably and easy restarts were nade up the hill in drive and reverse respectively.

I have already commented on the ease of driving the Commer ind the general standard of comfort given to the driver. The sus pension design was found to be very good and although inclined to roll a little when taking corners fast there was no effect from gusty side winds even when driving at maximum speed on the motorway or from uneven patches in the road.

Access to the van from the road into the driving seat is excellent and there is nothing to impede the driver if he wants to get into or out of the van from the nearside door. The test van had the optional passenger's and centre seat and these made a neat, three-man bench layout. Also incorporated on the test vehicle were sliding doors and these had a positive lock in the open position.

Insulation against noise and heat entering the cab was found to be very effective and accessibility to the engine is good when the hinged cover (carrying the centre seat) is raised. The coil, however, is mounted in a silly position and has to be removed for any attention to the distributor, which is located well down the side of the engine.

A point of criticism from the driving aspect is the small exterior mirrors fitted as standard. These do not give much of a view behind the vehicle and could well be replaced with the larger rectangular style now becoming more popular, even on lighter vehicles.

Reduction in driver fatigue is not the only reason for fitting automatic transmission on delivery work. The increasingly congested roads in our towns and cities calls for quite fantastic numbers of gear-change operations. Even with the best drivers, wear in clutches and transmission must be considerable.

Reports suggest that even drivers of average ability are few and far between nowadays and the first thing that gets affected by a bad driver or one who doesn't care is the transmission. It is obvious that substantial savings in cost must come with the fitting of automatic transmission, particularly in vans, and apart from the actual expense of having repairs carried out disorganization through loss of the vehicle for repair work is avoided.

In the circumstances the cost of the automatic option transmission on the Commer 1500 is well worth the £78 quoted. Basic price of the standard van as tested with petrol engine is £540. This is for the sliding-door version, the hinged-door design costing £475. In addition to the automatic transmission the test van had a heater which costs £12 17s. 6d., a passenger seat (£8 .10s.), a centre seat (£7 10s), a spare wheel, tyre and carrier (£15) and the cost of painting is £20.

As well as the 200 Cu. ft. van the Commer 1500 and 2500 series includes a number of versions such as 12and 14-seat buses. A hinged side-opening door can be incorporated and chassis-cab and chassis-front end versions are obtainable.