LIGHT VAN ID

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IGN

TIME FOR EW IDEAS

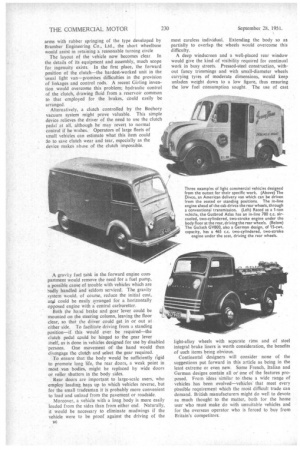

Present Price Trends are Forcing Tradesmen to Seek a Light Delivery Van Which, Like the Heaviest Vehicles, is Designed Especially for Commercial Application

By Alfred Wo(

S TATIST1CAL surveys are unnecessary to determine that rising costs and depreciation of the currency are the principal pre-occupation of most people. Tradespeople, just as much as wage-earners, are worried • by present trends, particularly when it has been their custom to provide a free service which is now making serious inroads into their finances.

Such is the case with the small shopkeepers and others who have been able to increase their earning potential by offering delivery services. With the exception of those who operate battery-electric vehicles, most of these people are now seriously disturbed by the heavy cost of delivery, particularly when it is not possible to plan deliveries on a door-to-door basis.

Fuel prices and mechanics' wages, the difficulty of securing safe and competent drivers at reasonable salaries, the attraction of the five-day week in industry —all these have their effect on the situation. In the circumstances, does the present light commercial vehicle meet existing needs?

Luxury Light Vans

Considering for the moment only those manufactured in quantity, it is clear that the basis of such models is usually a private car. But cars, in the main, are designed to provide comfortable, fast travel for four, five or six people and to continue to do so under the conditions pertaining in overseas markets; where, without doubt, the standard of living is high.

The export drive, in fact, is resnonsible not only for the extreme difficulty experienced in obtaining light vans of any capacity, but for the present design of many of the types produced. Doubtless excellent for the work which these chassis do as private cars, they do not approach the ideal specification for a light commercial vehicle.

Mechanical components are often inaccessible, and certain types of independent suspension tend to reduce front-wheel tyre life. Fuel consumption on local runs is high and the high speed possible with these vehicles encourages hare-brained driving, which results in battered bodywork, rapid deterioration of brakes and constant need for attention.

Attention to bodywork is expensive in the extreme, B4 although washing and polishing are much easier than they used to be. But to remove a dent in a mudguard caused by an encounter in a busy city street may require a whole day's work by a skilled panel-beater.

Returning to the fundamentals of the question; economy of operation and maintenance is the basic requirement of a light vehicle for a small tradesman. He cannot afford to have the vehicle off the road for more than a few hours. He would prefer a machine which his messenger-boy can service occasionally, and which can be repaired or overhauled in a few hours by the local garage hand.

Naturally, he wants a roomy vehicle, but he is not willing to pay for spaciousness in heavy fuel consumption. He wants a long-lasting vehicle, but not one that requires major attention every few months—most of it in the way of exchanging a complete unit for a reconditioned one. To-day's conditions demand, first, tow initial cost; secondly, low running costs; and, thirdly, long life and low depreciation.

The experience of large-scale operators, naturally, carries much weight. One was heard to say recently that he gave certain of his petrol-engined vans a life of five years. He was not sure about the battery-electric vehicles—one had been running for 20 years already. The small man, serving a rural community, or the city greengrocer with only one vehicle, cannot afford to devote special facilities to his transport.

if a cheap machine is to be made available, it must be backed by large-scale production. Therefore, an unconventional design powered by a type of engine not at present produced cannot be considered. What is needed is simply a reworked edition of some of the current types.

One of the most successful post-war British light commercial vehicles is the Bradford 10-cwt. Powered by a two-eylindered, horizontally opposed, water-cooled engine of just over 1-litre capacity, it has a great appetite for hard work, but a moderate thirst for fuel. On the Continent, this engine would power a vehicle of at least 1-ton capacity. This unit might well form the basis of an ideal design for the conditions under discussion. However, the ratio of load space to vehicle length is not exceptional in the Bradford van. In the interest of accessibility, the designers have placed the engine beneath a long bonnet. If the engine-gearbox unit were placed well ahead of the front wheels, as has been done with another product of the same concern, the available loading space would be much increased.

The load on the long transmission line would, of course, he greatly increased. Perhaps, therefore, frontwheel drive might be introduced. This would result in a body completely free of engine or transmission components, a low floor and easy accessibility to the entire running gear. Independent suspension and front wheel drive have proved to be economical as regards tyre wear. It might, in fact, prove possible to make the low floor the basis of the whole vehicle, and thus reduce weight by eliminating the chassis. Suitably braced, the floor would make an excellent basis for a chassisless vehicle.

Rear Engine Too Radical The restriction of the turning arc of the wheels which would occur because of the use of homo-kinetic joints for the front-wheel drive might have a limiting effect on the turning circle of the vehicle. This has been a difficulty with many front-wheel-drive machines. As an alternative, the engine, gearbox and transmission might be combined as a unit driving the rear wheels. This has been done in many instances on the Continent.

Conservative Britons, however, would probably prefer a front-mounted unit, ahead of the front Wheels, attached by bolts to the front of the frame, with the driver's seat above and between the front wheels. A high driving position has its advantages. Good vision is ensured, and with wide doors it should be particularly easy for the driver to gain access to the seat.

For the purposes of overhaul, the engine-transmission assembly could then be removed without disturbing the cab. The rear wheels being suspended on trailing

arms with rubber springing of the type developed by Bramber Engineering Co., Ltd., the short wheelbase would assist in retaining a. reasonable turning circle The layout of the vehicle now becomes clear. In the details of its equipment and assembly, much scope for ingenuity exists. In the first place, the forward position of the clutch—the hardest-worked unit in the "usual light van—promises difficulties in the provision of linkages and control rods. A recent Girling invention would overcome this problem; hydraulic control of the clutch, drawing fluid from a reservoir common to that employed for the brakes, could easily be arranged.

Alternatively, a clutch controlled by the Bochory vacuum system might prove valuable. This simple device relieves the driver of the need to use the clutch pedal at all. although he may revert to normal control if he wishes. Operators of large fleets of small vehicles can estimate what this item could do to save clutch wear and tear, especially as the device makes abuse of the clutch impossible.

A gravity fuel tank in the forward engine compartment would remove the need for a fuel pump, a possible cause of trouble with vehicles which are adly handled and seldom serviced. The gravity system would, of course, reduce the initial cost, andil could be easily arranged for a horizontally opposed engine with a central carburetter.

Both the hand brake and gear lever could be mounted on the steering column, leaving the floor clear, so that the driver could get in or out at either side. To facilitate driving from a standing position—if this would ever be required—the clutch pedal could be hinged to the gear lever itself, as is done in vehicles designed for use by disabled persons. One movement of the hand would then disengage the clutch and select the gear required.

To ensure that the body would be sufficiently rigid to promote long life, the rear doors, a weak point in most van bodies, might be replaced by wide doors or roller shutters in the body sides.

Rear doors are important to large-scale users, who employ loading bays up to which vehicles reverse, but for the small tradesman it is probably more convenient to load and unload from the pavement or roadside.

Moreover, a vehicle with a long body is more easily loaded from the sides than from either end. Naturally, it would be necessary to eliminate mudwings if the vehicle were to be proof against the driving of the most careless individual. Extending the body so as partially to overlap the wheels would overcome this difficulty.

A deep windscreen and a well-placed rear window would give the kind of visibility required for continual work in busy streets. Pressed-steel construction, without fancy trimmings and with small-diameter wheels carrying tyres of moderate dimensions, would keep unladen weight down to a low figure, thus ensuring the low fuel consumption sought. The use of cast

light-alloy wheels with separate rims and of steel integral brake liners is worth consideration, the benefits of such items being obvious.

Continental designers will consider none of the suggestions put forward in this article as being in the least extreme or even new. Some French, Italian and German designs contain all or one of the features proposed. From ideas similar to these a wide range of vehicles has been evolved—vehicles that meet every pbssible requirement which the most difficult trade can demand. British manufacturers might do well to devote as much thought to the matter, both for the home user who must make do with unsuitable vehicles and for the overseas operator who is forced to buy from Britain's competitors.