RAN IA - 1„

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Interfit

By L. J. COTTON, M.I.R.T.E.

DURING the hottest part of the year, when the sun temperature was about 160 degrees F. and shade readings of 120 degrees were common, I spent 15 days in Iran travelling on British and foreign commercial vehicles to study their performance under the worst possible conditions. Iran was chosen for this summer " vacation " because it is tropical and provides topographical variety ranging from desert in the south to mountain in the north.

I left England by air one Saturday evening, called at Cairo for breakfast next morning, and landed at Abadan in the early afternoon. There were over 1,000 miles of dull, yellow-grey desert to study from the air between Cairo and Basra, without a single tree or glimpse of water to break the monotony.

Abadan, with its great growth of date palms, huge refinery, abundance of oil tankers and surrounding rivers, was almost a welcome sight. I left the aeroplane at Abadan airport and stepped out into an oven-blast temperature of 157 degrees, which I soon found was normal in the sun. The array of Austin and Humber cars, together with same well-maintained Bedford coaches, standing outside the airport, reminded me of home, 3,450 miles away. I enjoyed a cool drink while waiting for my kit to be cleared through the Customs, and then went to the guest house.

Although I landed on a Sunday, it was a working day in Abadan, because the Mohammedan day of worship (Friday) is the accepted day of rest in the Middle East. At 3 o'clock in the afternoon, when I was driven to the guest house, the roads were practically deserted, and except for a few shift workers, the remainder of the population appeared to be wisely indulging in a siesta, because work starts at 5.30 a.m., with a short break for lunch at 10 a.m., and finishes in the hottest part of the day, about 2.30 p.m. The heat was intense, both indoors and out. The thermometer hanging in my room showed 109 degrees during the day and fell to 104 degrees during the coolest part of the night. Water from the cold tap in the bathroom was at the right temperature for shaving, and, of the two, the static water from the hot tank was the cooler.

Abadan is a modern town, surrounded by rivers, which has been built around the largest refinery in the world. With the exception of a bazaar and Affi's general store, the town has been constructed by the AngloIranian Oil Co., and its 110,000-population is entirely dependent on the oil company for its employment, transport, electricity, food, welfare, public works and, in fact, all its amenities.

Border Restrictions My programme for the tour was organized in conjunction with the oil company, and arrangements were made for me to visit its installations and repair shops, and vehicles were placed at my disposal for testing in all parts of the country. Whilst giving every possible assistance in Iran, the company could not obtain a visa for my entry to Basra, in Iraq, and the first morning of my stay was spent in the waiting room of the Iraq Consulate at Khorramshahr, but the Consul did not put in an appearance that day.

travelled out to the Consulate again the following morning, the journey involving a 12-mile car ride and a river crossing on a Gardner-engined ferryboat, to be eventually conducted into the presence of the Consul. After examining my passport he informed rue that a visa would not be granted, because I was a journalist. This cramped my activities and my tour had to be reorganized.

This was only one of many difficulties encountered during my stay in the country. I spent almost a week inspecting garages, repair shops, the drivers' training school, and travelling on all types of commercial vehicle operating in the Abadan area. During this period I learned of the many difficulties of maintaining a fleet of 3,600 ears, lorries and buses of many makes and types under tropical conditions. Because of climatic and road conditions, these vehicles are mostly written off and replaced at five-yearly intervals.

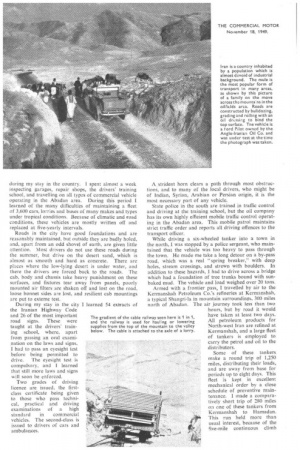

Roads in the city have good foundations and are reasonably maintained, but outside they are badly holed, and, apart from an odd shovel of earth, are given little attention. Most drivers do not use these roads during the summer, but drive on the desert sand, which is almost as smooth and hard as concrete. There are places where the low-lying desert is under water, and there the drivers are forced back to the roads. The cab, body and chassis take heavy punishment on these surfaces, and fixtures tear away from panels, poorly mounted air filters are shaken off and lost on the road, loose bonnet sides are lost, arid resilient cab mountings are put to exteme test.

and 26 of the most important road signs. These were taught at the drivers' train ing school, where, apart from passing an oral examination on the laws and signs, I had to pass an eyesight test before being permitted to drive. The eyesight test is compulsory, and I learned that still more laws and signs will soon be enforced.

Two grades of driving licence are issued, the firstclass certificate being given to those who pass techni cal, practical and driving examinations of a high standard in commercial vehicles. The second-class is issued to drivers of cars and ambulances.

A .strident horn clears a path through most obstructions, and to many of the local drivers, who might be of Indian, Syrian, Arabian or Persian origin, it is the most necessary part of any vehicle.

State police in the south are trained in traffic control and driving at the training school, but the oil company has its own highly efficient mobile traffic control operating in the Abadan area. This mobile patrol maintains strict traffic order and reports all driving offences to the transport officer.

While driving a six-wheeled tanker into a town in the north. I was stopped by a police sergeant, who maintained that the vehicle was too heavy to pass through the town. He made me take a long detour on a by-pass road, which was a real "spring breaker," with deep holes, stream crossings, and strewn with boulders. In addition to these hazards, I had to drive across a bridge which had a foundation of tree trunks bound with sunbaked mud. The vehicle and load weighed over 20 tons.

Armed with a frontier pass, I travelled by air to the Kermanshah Petroleum Co.'s refineries at Kermanshah, a typical Shangri-la in mountain surroundings, 300 miles north of Abadan. The air journey took less than two hours, but by road it would have taken at least two days. All petroleum products for North-west Iran are refined at Kermanshah, and a large fleet of tankers is employed to carry the petrol and oil to the distributors.

Some of these tankers make a round trip of 1,250 miles, distributing their loads, and are away from base for periods up to eight days. This fleet is kept in excellent mechanical order by a close schedule of preventive maintenance. I made a comparatively short trip of 280 miles on one of these tankers from Kermanshah to Hamadan. This run held more than usual interest, because of the five-mile continuous climb over the Asadabad Pass and the history attached to the route.

Asadabad has a strong link with the original province of Persia (renamed Iran in 1936), and carvings now being discovered on the mountain face date back over 2,000 years, when the Greeks first waged war in Persia. In recent history, the road from Kermanshah to Asadabad and Hamadan formed part of the overland aid-to-Russia route to the Caspian Sea.

Travelling facilities in Iran are poor, and apart from a very limited coach service operating between Baghdad and Teheran, the population of the north practically relies for transport on "hitch-hiking" on commercial vehicles. It is not unusual to find up to eight passengers in the cab of a forward-control lorry, and the maximum human "payload" I saw on any commercial vehicle comprised 34 people clinging to the exterior riggings of a Mack petrol tanker. Driving a commercial vehicle in Iran can be made a profitable business.

Compared with the size of the oil company's fleet, the number of vehicles operated by independent hauliers is small. Most of these vehicles are of American manufacture, and although new Chevrolet vans and lorries are

steadily gaining in number, most of the lorries run by hauliers are aged. l saw several Macks, with chaindriven rear axles, carrying enormous loads in Abadan, their mudguards touching the wheels at every bump and corner. Breakdowns are frequent, and it is not unusual to find an axle overhaul being done by the roadside.

The oil company supports this private enterprise, and the hauliers are engaged, under contract, to shift stores in the south and assist in distributing oil and petrol from the Kermanshah refinery. The Mack tankers, working over the Asadabad Pass, arc fitted with oil engines and the black smoke from their exhausts is seen long before the vehicles arrive in sight.

I could not leave the country without visiting the oil fields to see the commercial vehicles operating under some of the most difficult conditions in the world, carrying boring and pipe-line equipment. [flew to Masjid-iSulaiman (MIS.), the first oilfield of the Anglo-Persian Oil Co. (the former title of the present company). The original pipe-line between M.I.S. and Abadan, constructed in 1911, had an annual capacity of 400,000 tons; over 24,000,000 tons of crude oil are now piped to Abadan every 12 months.