ADY FOR ANYTHING

Page 61

Page 62

Page 63

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

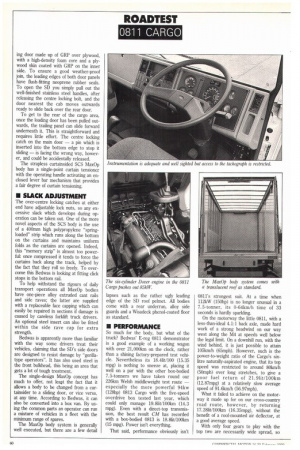

Bodybuilder Bedwas has put its MaxOp three-way access body on an lyeco Ford 0811 Cargo and come up with an interesting demonstrator for high-street distribution.

• Twenty years ago you could have stood on a bridge over a motorway watching the traffic and be sure of two things: that with a few odd exceptions all the trucks were British, and the most popular form of body was the ubiquitous flat.

Those days are gone. Foreign truck builders may not be getting it all their own way, at least at 7.5 tonnes, but the once fanatical following for the flat has long since waned, along with the love of greasy tarpaulins and serpentine coils of rope. A flat may be the easiest thing in the world to load — but when it comes to security or image, forget it.

Recent changes in distribution, and the ever-increasing clout of the large retail chains, have helped to send the flat into its final downward spin. It's clear that when it comes to deliveries the supermarkets want the goods in a box. The only trouble with a box body is getting into it: like it or not, whatever you put in first has to come off last.

Enter the curtainsider, or to give it its high falutin' title, the rapid side-access body. Whether mounted on a rigid or a trailer, here is a body that protects the load from the elements while allowing unloading flexibility. As a cross between the curtainsider and the box comes the sliding-side box body, offering the same basic concept of the curtainsider but with more security. It is, after all, more difficult to slash through a 25mm-thick solid panel with a Stanley knife than a thin plastic curtain. Each of these bodies has its pros and cons, and in this week's road test we try out a delivery truck with a clear case of schizophrenia.

When the Newport, Gwent-based bodybuilder Bedwas was looking at the best way to show off its MaxOp side-access body system, it had the bright idea of fitting one side of the body with its SCS strapless side curtain, and the other with its SD flush-sided sliding door package.

Put the whole shooting match on Bedwas' own 81kw (110hp) lveco Ford 0811 Cargo demonstrator chassis and you have the ideal road test vehicle for our bodybuilding issue.

Bedwas has built up a solid reputation for its security vehicle bodywork (it belongs to the Securicor Group) and it now aims to break into a number of new markets, not least the side-access sector. It is facing formidable competition, of course, from the likes of Boalloy, Southfields, Don-Bur and Lawrence David.

The MaxOp SCS strapless curtainsider was launched in May 1987; the SD slidingside door version followed a year later. The range was further extended at the Birmingham Show last October by an insulated version of the SD, the ISD, for controlled-temperature operators.

At the same time it made a number of minor changes to its MaxOp range; these have become standard on all 1989 bodies. They include redesigned over-centre cam locking rollers to give smoother closing, better security and low maintenance requirements. The SCS MaxOp also has a revised bottom roller design for the integral, steel load support bars which are set at 100mm intervals.

Like Boalloy's popular One Seven/ Seven-5-Liner design, the MaxOp body range is based on a standard frame which allows fitting of doors, curtains, tensioned curtains or any combination thereof. All versions are available with a choice of steel or alloy subframes. In the case of our split-personality demonstrator the front and rear pressings are of zinc-plated steel, with the standard twin rear doors made up of a sandwich of an outer alloy skin over WBP ply, with a galvanised steel skin covering the interior.

The MaxOp SD has a 25mm-thick slid ing door made up of GRP over plywood, with a high-density foam core and a plywood skin coated with GRP on the inner side. To ensure a good weather-proof join, the leading edges of both door panels have flush-fitting neoprene rubber seals. To open the SD you simply pull out the well-finished stainless steel handles, after releasing the centre locking bolt, and the door nearest the cab moves outwards ready to slide back over the rear door.

To get to the rear of the cargo area, once the loading door has been pulled outwards, the trailing panel can slide forward underneath it. This is straightforward and requires little effort. The centre locking catch on the main door — a pin which is inserted into the bottom edge to stop it sliding — is facing the wrong way, however, and could be accidentally released.

The strapless curtainsided SCS MaxOp body has a single-point curtain tensioner with the operating handle activating an enclosed lever bar mechanism that provides a fair degree of curtain tensioning.

• SLACK ADJUSTMENT

The over-centre locking catches at either end have adjustable lock nuts, so any excessive slack which develops during operation can be taken out. One of the more novel aspects of the SCS body is the use of a 400nun high polypropylene "springloaded" strip which runs along the bottom on the curtains and maintains uniform folds as the curtains are opened. Indeed, this "memory strip" is almost too powerful: once compressed it tends to force the curtains back along the track, helped by the fact that they roll so freely. To overcome this Bedwas is looking at fitting click stops in the bottom rail.

To help withstand the rigours of daily transport operations all MaxOp bodies have one-piece alloy extruded cant rails and side raves; the latter are supplied with a replaceable face capping which can easily be repaired in sections if damage is caused by careless forklift truck drivers. An optional steel insert can also be fitted within the side rave cap for extra strength.

Bedwas is apparently more than familiar with the way some drivers treat their vehicles, claiming that the SD's side doors are designed to resist damage by "gorillatype operators". It has also used steel in the front bulkhead, this being an area that gets a lot of tough treatment.

The single-design MaxOp concept has much to offer, not least the fact that it allows a body to be changed from a curtainsider to a sliding door, or vice versa, at any time. According to Bedwas, it can also be converted into a box van. By using the common parts an operator can run a mixture of vehicles in a fleet with the minimum range of spares.

The MaxOp body system is generally well executed, but there are a few detail lapses such as the rather ugly leading edge of the SD roof pelmet. All bodies come with a rear undernm, alloy side guards and a Wisadeck phenol-coated floor as standard.

• PERFORMANCE

So much for the body, but what of the truck? Bedwas' E-reg 0811 demonstrator is a good example of a working wagon with over 21,0001im on the clock, rather than a shining factory-prepared test vehicle. Nevertheless its 18.4Iit/100 (15.35 mpg) is nothing to sneeze at, placing it well on a par with the other box-bodied 7.5-tonners we have taken round our 2261cm Welsh middleweight test route — especially the more powerful 94kw (128hp) 0813 Cargo with the five-speed overdrive box tested last year, which could only manage 19.81it/100km (14.3 mpg). Even with a direct-top transmission, the best result CM has recorded with a box-bodied 0813 is 18.8lit/100km (15 mpg). Power isn't everything.

That said, performance obviously isn't 0811's strongest suit. At a time when 112kW (150hp) is no longer unusual in a 7.5-tonner, its 0-64km/h time of 33 seconds is hardly sparkling.

On the motorway the little 0811, with a less-than-ideal 4.1:1 back axle, made hard work of a strong headwind on our way west along the M4 at speeds well below the legal limit. On a downhill run, with the wind behind, it is just possible to attain 105km/h (65mph). However, such is the power-to-weight ratio of the Cargo's sixlitre naturally-aspirated engine, that its top speed was restricted to around 80km/h (50mph) over long stretches, to give a poor fuel return of 21.91it/100km (12.87mpg) at a relatively slow average speed of 91.6km/h (56.97mph).

What it failed to achieve on the motorway it made up for on our cross-country road route, however, by returning 17.28k/100km (16.35mpg), without the benefit of a roof-mounted air deflector, at a good average speed.

With only four gears to play with the top two are necessarily wide spread, so the engine has to be revved quite hard before changing up. Top gear was much in demand, making best use of the engine's flexibility: maximum torque was available down to around 50kmih. When it comes to hill climbing, second gear is generally up to the job.

• CAB COMFORT

Gear shifting is light and precise but the gear lever is located just a little too far back for comfort.

The clutch pedal is on the heavy side for a local distribution vehicle which can be expected to spend a lot of its time in traffic. Steering, on the other hand, is light and gives good directional response without having to over-correct. Our E-reg test vehicle was one of the last to be built with the old drum brake system which gives very little feel or progression: light pedal effort gives virtually no retardation, while a little more movement can make the cab dip quite violently. Ford has since changed to Girling ventilated disc brakes and these are much easier to control. There is enough seat adjustment to suit most drivers and a contoured backrest gives good support. The ride is by no means uncomfortable, but some form of suspension could only be an advantage in supplementing the road springs. Noise levels are quite acceptable, especially at normal road speeds.

The cab step provides clear, easy access and once inside the low front screen and deep glazed door panels give good visibility where it is most needed to negotiate congested streets.

Instrumentation is adequate and well sighted, but access to the tachograph is restricted by the steering wheel and its surround seemed prone to become detached from the fascia. The heater warmed the cab well, but only seemed capable of giving all or nothing.

Daily servicing is handled by access to engine coolant and engine-oil dipstick at the side of the vehicle, and to the screen washer and clutch reservoirs behind a front grille panel which can be opened with the aid of a coin.

• SUMMARY

The fact that this 0811 Cargo was provided out of service, as opposed to our usual lines of supply from the chassis manufacturer, only serves to commend its overall performance. With only four gears and 85kW (114hp) of power it is clearly not intended for motorway operation, but copes very well with A-road running, giving good average journey times without expensive fuel bills, even without the luxury of a roof-mounted spoiler.

While the trend at 7.5-tonnes is towards engines pumping out at least 100kW (135hp), not everyone needs that level of performance — for the average operator running in town the 0811's 85kW will be more than enough.

Bedwas is obviously keen to extend its coverage in the UK bodybuilding market and its MaxOp system offers good flexibility. A typical price for a 4.92m MaxOp strapless curtainsider is £3,547 nett for an unpainted version. This compares to £3,795 for a conventional 5.02m Boalloy Seven-5-Liner curtainsider with straps and a slightly higher specification.

The overall finish of both the SCS and SD MaxOp styles is good — but then so are the bodies of its main rivals. If Bedwas is to make a name for itself then its side access system must, above all else, be durable, for while price is a major concern for hauliers buying bodywork a repu tation for strength in the face of adversity frequently wins the day when orders are being placed.

Only two years after its launch it is difficult to comment on the MaxOp's longevity, but if it is built with the same strength as Bedwas' security vehicles it should last the course.

by Bill Brock