losing the gap

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Cranfield Centre for Transport Studies aims to bring fleet operators and suppliers together. In this series, Derek Wright gets behind the jargon to explore the financial benefits of high technology

SO FAR in this series I have concentrated on vehicle technology and related issues. There are a number of reasons for tackling the problems which face the road freight industry in this way. We are not, of course, looking at all problems — only those connected with computer applications. It is the truck that operators claim makes this industry different from other businesses.

Additionally, most businesses in road freight have fleets of less than five vehicles. These companies can now consider using the cheaper microcomputers available, perhaps for the first time. Another reason for using what is termed a "bottom up" approach rather than the conventional "top down" approach arises because in many larger organisations with sufficient knowledge of using computers for data processing, there is a poor level of awareness of the technical applications becoming possible.

In the article last month (Closing the Gap, CM, March 2) I discussed:

• advantages of using a computer to store and prepare information on individual vehicle maintenance; • using a computer in this system to provide a more effective check on the repair costs of the lorries and the fleet; and • widening of the scope of the system bringing further gains in indirect cost centres, such as helping to improve workshop planning and efficiency, as well as providing information on faults common to other vehicles in the fleet, tracing warranty claims, and so on.

The Institute of Mechanical Engineers recently held a conference to discuss the developments in vehicle condition monitoring and fault diagnosis. It was noticeable that among those contributors from vehicle manufacturers an engineer from Daf seemed in a minority. It was not that Daf is any less enthusiastic and certainly no less capable of the technical development and manufacture of such systems, but simply that, while many others primarily addressed the technical question of how, he was equally interested in whether operators would be better able to run their businesses effectively.

It is an important point and one which in our experience is not considered nearly as often as necessary.

In this particular instance the point related to how businesses whose vehicles do not return to the operating centre daily would have a different requirement of diagnostic monitoring equipment from, say, a bus operator whose vehicles return to the same garage on a daily basis.

In the wider context it is the recognition of using the technology to fit the business need rather than creating a demand for the technology solutions we find easy; spending time improving our performance in areas we know we can solve rather than seeking solutions to the actual problems.

The remarks are a little exaggerated to make the point and there is also the danger in advocating designs or systems that attempt to satisfy every operator's need.

The operator's real need is for reliable vehicles, greater vehicle reliability automatically reducing unscheduled repair: and the demand for diagnostic systems. There is a need to en sure that technology, compu ters included, is appliec correctly and not just in thr areas of technical expedience.

Even as vehicles becorm more reliable it will be sorni years before they are trul' maintenance free throughou their operating life. Histori records of work done will be re quired for cost accounting an' allocation for some time int. the future.

Some operators discoverin the advantages of using corr puters have suggested the vehicle replacement is an are where a computer-based mar agement information syster should be used.

There are two factors whic should encourage people in tt transport industry to make better effort in specifying ar buying vehicles than perhar has been the case in the past.

First, rising interest rates ensure that the cost of buying vehicles is high; it has been the case for the past five years and rates are likely to remain at the relatively high levels into the near future. Consequently, vehicles are expensive and must be used for their maximum useful life.

Second, the development of the microcomputer has permitted the use of electronics to produce management information cheaply, the cheapness providing the incentive and enthusiasm for using the machines in operational areas of the business as well as in the usual areas invoicing, wages, and so on.

Operators have many different ways of deciding when to replace vehicles; not all methods employ logical economic arguments. A computer may help in some instances. As I have observed earlier, we must analyse the information needed, then we can decide on the best way of obtaining these facts. The economic theory used to decide when vehicles should be changed is based upon relatively simple factors.

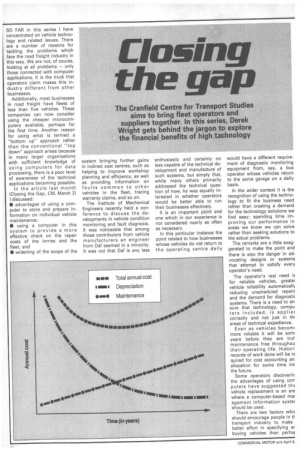

The replacement theory used two prime inputs: depreciation of the capital and operating costs, annual costs which decrease as time and/or mileage increases, and increasing costs with time, servicing and repairs. If the figures were sketched on a graph then the theory predicts a shape like that represented opposite.

The aim is to keep the vehicle long enough to reduce the capital cost per year but not so long that repairs and maintenance become exorbitant. There is a wide variety of computer software packages that will carry out these calculations.

The situation looks useful but in practice is not so simple. True, the depreciation according to the rules of accountancy would give a smooth curve, but the figure we depreciate can vary. The more exact we try to make the sums the more complex and more open to judgment the results become.

First, the secondhand market for trucks varies and the true value of the lorry will reflect not just its age but also the mileage, body condition, body type, model popularity as well as the health of the industry, the cost of new vehicles and the rate of inflation.

Notice that we are discussing the real depreciation of the capital tied up in the vehicle, not the allowances made for tax purposes. It would be possible to enter estimates for all these factors on each vehicle in the fleet into a program on a computer and it would happily carry out the calculations.

The other set of annual costs required are the maintenance figures. We expect to spend more on repairs as vehicles get older and mileage increases, but it is unlikely to be the same increase each year, so the graph of maintenance would in fact have many peaks and troughs if drawn accurately.

However, if required, it would be possible to make reasonably accurate predictions of the likely repair costs, with allowances for inflation, wage rises for workshop staff, etc. To improve the system it would be possible to continually review the position by accessing the sort of data available from the maintenance packages we referred to in the earlier article.

In essence, with each report of vehicle costs it would be possible to identify those vehicles whose costs were rising and therefore ought to be replaced. Clearly, the size of computer required is beginning to increase as each increased level of sophistication is added and we really must consider the information actually required for replacement. Just looking at the age which provides the lowest annual costs disguises many other costs which could arise, perhaps in other cost centres: hidden in overheads.

Older vehicles requiring more work need workshops and workshop staff; break down more often, disrupting the distribution activity and upsetting customers and this will add to costs.

Newer vehicles may be considered good pr for the public image as well as with drivers, and reduce the need for workshops and workshop staff. They may also have improved distribution performance through high average road speeds, lower fuel consumption, lower unladen weight. Each of these factors can be important to the business, overshadowing the "economic life". These are subjective factors and so any computer system not incorporating estimates of these effects on the whole business (possible, but unlikely to be feasible) becomes a decision support system (DSS).

In this role a computer program as part of a system of, say, maintenance, or vehicle costing, may be useful.

A more complex problem associated with vehicle replacement is also being tackled with the aid of a computer.

Vehicle manufacturers have for some years used computer analysis to match engine, transmission and vehicle characteristics to achieve optimum road performance. These same techniques have been applied and now enable truck operators to specify the characteristics of the load and route. The information gained from sending a fully instrumented truck over various routes in the UK enables the staff at Mercedes Transport Consultants to predict the operating costs for different vehicle types and specifications. This sophisticated program can demonstrate the differences in vehicle specification required for, say, minimising cost or minimising journey times a very useful facility for transport managers.

Getting the specification right is just the start of keeping costs under control and many companies offer computer program for handling fleet costs. Next month I will examine some of the differences of the main products on offer.