AIMING HIGH FOR MARS

Page 46

Page 47

Page 55

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by CM reporter Pictures by Dick Ross

Servicing the distribution requirements of round-the-clock confectionery production

WHEN a factory works 24 hours a day, seven days a week, producing national branded goods, has no buffer storage and runs no vehicles of its own, the service it requires from the haulage industry is very demanding. When those goods also need protection from heat, humidity, sunlight and rough handling, have a limited shelf life and have to be delivered in strict rotation, the service must also be pretty sophisticated.

Mars Ltd, of Slough, has contracted for this level of service from Southern British Road Services Ltd, whose branch at Bedfont, Middlesex, is devoted entirely to handling Mars products and is highly integrated with the factory it serves. Documents produced jointly by Mars' computer and BRS loadplanners are at the heart of the distribution system.

The 11,612sqm (125,000sqft) warehouse at Bedfont dispatches 40,000 cases of confectionery each day, round the clock, and the depot employs 88 drivers on a job-and-finish basis, to deliver direct in London and the Home Counties and to trunk on shuttle services with 19 vehicles to outlying areas. The vehicles, which are 3-ton to 10-ton boxvans, were leased from Ford when the previous owners of the depot (Translloyd handled the Mars traffic, but whei BRS took over this depot complet with staff and vehicles in 1972 bought the vehicles and put them o contract hire to Mars.

Since that take-over in AugtH 1972, Southern BRS has been respor sible for warehousing and distributin Mars confectionery over the whole c Southern England up to the Bristc Channel/The Wash line, and througl" out Scotland via Tartan Arro, container services and several Nation Freight Corporation carriers north the border.

Western BRS vehicles undertat the Devon and Cornwall distributioi picking up the loads trunked down t Exeter by Southern BRS. T1 Midlands and the North are tF responsibility of Harris Roo Services in a totally separa: operation.

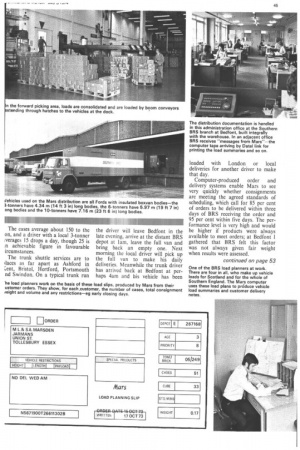

Most of the London deliveries a] made with 3-tonners, the 10-tonne do the bulk of the outer urbo deliveries and the shuttle Tuns, whi the 6-tonners are used in varying pri portions on local, outer urban at long-distance work. The low-profi van bodies have polystyrene i sulation between double aluminiu alloy skins; most of them ha' double rear doors, but some sid loaders are being tried. The cases average about 150 to the on, and a driver with a local 3-tonner .verages 15 drops a day, though 25 is .n achievable figure in favourable ircumstances.

The trunk shuttle services are to daces as far apart as Ashford in :.ent, Bristol, Hertford, Portsmouth nd Swindon. On a typical trunk run the driver will leave Bedfont in the late evening, arrive at the distant BRS depot at lam, leave the full van and bring back an empty one. Next morning the local driver will pick up the full van to make his daily deliveries. Meanwhile the trunk driver has arrived back at Bedfont at perhaps 4am and his vehicle has been loaded with London or local deliveries for another driver to make that day.

Computer-produced order and delivery systems enable Mars to see very quickly whether consignments are meeting the agreed standards of scheduling, which call for 85 per cent of orders to be delivered within three days of BRS receiving the order and 95 per cent within five days. The performance level is very high and would be higher if products were always available to meet orders; at Bedfont 1 gathered that BRS felt this factor was not always given fair weight when results were assessed. Each day's distribution plan starts at 4.30 pm when Mars amalgamates its batch of orders and punches them into the main computer, which produces "load slips", each 200 mm x 100mm (7% in x 4in) showing the weight and bulk of each customer's order, the region and sales "brick" in which that customer's premises lie, and any special instructions or limitations.

These slips — about 2,000 a day. are printed out from punched tape at the . BRS Bedfont computer terminal, starting at 5am on the following morning, and when the four load planners arrive for their 6am to 2 pm shift they work rapidly to make the individual load slips up into vehicle loads.

By Sam the vehicle load plans for Scotland are being transmitted from the Bedfont keyboard to the Slough computer, and by 1 1 am the English load plans have also been sent through.

The computer uses this information to produce a load summary for each vehicle — showing the number of cases of each product which it will need to carry — and this, on arrival at Bedfont, forms the basis for the order-picking in the BR S warehouse. (It arrives by Datel Link as tape and is printed out on a computer printer). Summarizing loads by product is a system which has obvious advantages in saving warehouse time and in providing for rapid daily stocktaking of individual commodities (there are no fewer than 120 different product lines held in the store) but it produces problems for the delivery driver. He has a van loaded with enough of the right goods to meet his delivery instructions, but not in customer batches or in drop order, and so at each drop must clamber about selecting cases.

Angled floors

This has been eased to some extent by loading the vehicles along the sides, to leave a central ganevay — and the floors are angled so that the cases lean outwards, against the vehicle sides. Drivers have a sack-barrow for shop deliveries.

If, as BRS believes, there would be overall advantages in changing the documentation, or loading by delivery note in reverse-drop order, then it is up to the haulier to quantify the savings and convince the customer that both parties could benefit. The imminent cutting of daily driving hours will affect the economics of this.

Southern BRS accepts that working towards greater overall efficiency, so that savings can be passed on to customer as well as enjoyed by the haulier, is part and parcel of such a closely integrated relationship where the operator is assured of regular tonnages at realistic rates.

Picking and loading

As well as producing a load summary sheet for each vehicle, the Mars computer produces individual customer delivery notes in full detail (again, transmitting these by punched tape, to be printed out at Bedfont) and automatically adjusts the stock level records for the warehouse by debiting the day's orders.

The computer also adjusts the stock levels upwards when each bulk consignment is delivered from factory to warehouse by a regular shuttle service run by a private haulier — Fullers Transport. This employs two tractive units and four 40ft semi-trailer boxvans round the clock, involving 24 daily loads of 22 pallets — each pallet carries one product but the loads are mixed. There are 10,000 1016mm x 1219 mm (401n x 48 in) pallet spaces in the warehouse, and BRS tries to store like with like.

The whole warehouse operation is controlled by a Strafoplan system, using coloured tabs to show the position of every pallet space and the product occupying it.

Three copies

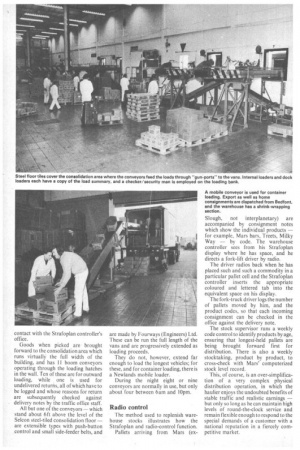

Three copies of each vehicle load summary are received by the warehouse (another one goes to the driver and one to the office). Of the warehouse copies, one goes to the order picker, one to the loader in the forward picking area and one to the outside loader on the bank. The need for separate copies for the latter pair stems mainly from the fact that vehicle loading is through hatches in the warehouse wall at vehicle deck height; so, apart from small communicating doors, there is no direct access between the warehouse load consolidation area and the actual loading bank.

This solid wall with loading hatches was designed to help maintain the temperature in the warehouse and limit the ingress of sunlight. (The whole warehouse is temperature and humidity controlled.) But one suspects there may also have been a nod in the direction of security.

The products are listed on the load summaries in the same order as the load cells in the warehouse, so the picker can go snake-like down the aisles, picking from each side. Everything in the store is on pallets, and the handling is by forklift and pallet trucks rented from Lansing Bagnall on terms which include maintenance. Each truck is in radio contact with the Strafoplan controller's office.

Goods when picked are brought forward to the consolidation area which runs virtually the full width of the building, and has II boom conveyors operating through the loading hatches in the wall. Ten of these are for outward loading, while one is used for undelivered returns, all of which have to be logged and whose reasons for return are subsequently checked against delivery notes by the traffic office staff.

All but one of the conveyors — which stand about 6ft above the level of the Selcon steel-tiled consolidation floor — are extensible types with push-button control and small side-feeder belts, and are made by Fourways (Engineers) Ltd. These can be run the full length of the vans and are progressively extended as loading proceeds.

They do not, however, extend far enough to load the longest vehicles; for these, and for container loading, there is a Newlands mobile loader.

During the night eight or nine conveyors are normally in use, but only about four between 6am and lOpm.

Radio control

The method used to replenish warehouse stocks illustrates how the Strafoplan and radio-control function.

Pallets arriving from Mars (ex Slough, not interplanetary) are accompanied by consignment notes which show the individual products — for example, Mars bars, Treets, Milky Way — by code. The warehouse controller sees from his Strafoplan display where he has space, and he directs a fork-lift driver by radio.

The driver radios back when he has placed such and such a commodity in a particular pallet cell and the Strafoplan controller inserts the appropriate coloured and lettered tab into the equivalent space on his display.

The fork-truck driver logs the number of pallets moved by him, and the product codes, so that each incoming consignment can be checked in the office against the delivery note.

The stock supervisor runs a weekly code control to identify products by age, ensuring that longest-held pallets are being brought forward first for distribution. There is also a weekly stocktaking, product by product, to cross-check with Mars' computerized stock level record.

This, of course, is an over-simplification of a very complex physical distribution operation, in which the haulier enjoys the undoubted benefits of stable traffic and realistic earnings — but only so long as he can maintain high levels of round-the-clock service and remain flexible enough to respond to the special demands of a customer with a national reputation in a fiercely competitive market.