Robust and

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Lively — The M.T.N •

Eagle

By Laurence J. Cotton, M.I.R.T.E. WHEN testing the Eagle 6-7-tonner I was reminded of John Ruskin's wisdom, There is hardly anything in the world which some man cannot make a little Wbrse and sell a little cheaper and the people who consider the price only are this man's lawful prey." If Ruskin had lived in the latter part of the 20th century, and had knowledge of road transport, he would have had a-standard by which to judge others--in the M.T.N.

In common with other models builtby Motor Traction, Ltd., the Eagle is hand assembled with the traditional skill of the pre-war fitter. The frame is a reamed-fit assembly and all the component parts are planned for• ample reserve in the transmission and braking. For• example, the gearbox, propeller shafts and driving shafts could operate with a 10 per cent. greater torque than that produced by the Gardner. 4LW by which the Eagle is -powered, and the braking would be adequate for a vehicle of con

siderably greater load-carrying capacity.

The Gardner four cylindered engine, of normal rating-230 lb. .ft. torque at 1,000 r.p.m.—is employed to afford a safe margin for the Meadows 250C-05 gearbox, which is designed for vehicles of medium range and has a torque capacity for 250 lb.-ft. This is a new overdrivetop unit, four ratios being in constant mesh, with the shafts carried on roller bearings to promote quiet operation. It is retained as a unit with the engine and 14-in.-diameter clutch, on a Gardner conventional mounting, and a hydraulic damper is employed to control torque reaction. Layrub heavy duty propeller shafts, type 100, with a centre support-bearing carry the transmission to the hypoid-driven rear axle. The rear springs are underslung. Formerly, cheek bushes were employed at the spring pins to prevent chafing in the brackets, but a modification has been introduced to employ a plain phosphor-bronze bush with flanged discs of the same material.

In keeping with other chassis built by Motor Traction, Ltd., the Eagle has the Clayton Dewandre 6.87-in. servo operating through a Lockheed hydraulic system to Girling highcentre-lift shoes. This system is well protected againstioss of pedal travel when the drums are expanded, and the triple-pull hand brake is especially effective with the linkage of the high-lift shoe.

Although the Eagle is built alongside the Rutland Albatross and Stuka, and employs certain components in common, it will be marketed through separate distributors. This is considered the best method of enabling Albatross and Stuka users to obtain Perkins-engined chassis spares from a Rutland agent, and stores for the Eagle, and subsequent Condor, will be held by a separate M.T.N. distributor, thereby avoiding confusion in ordering.

Because Of the heavier power unit, larger clutch and sturdier engine mounting, the Eagle weighs almost 10 cwt. more than its predecessors equipped with the Perkins sixcylindered oil engine. Operators of Gardner-engined vehicles are prepared to accept the higher unladen weight, but expect the chassis as a whole to have the same high quality making for longevity between periods of maintenance or overhauling. This they will find in the Eagle.

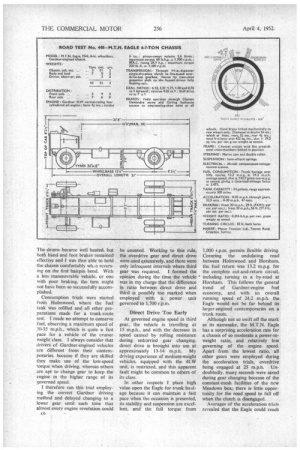

the-customary 7-ton load of concrete blocks,. representing body and payload, via imposed on the frame. in readiness for my trials, and the

gross weight, withont crew, registered 10 tons 12* cwt. The tyre equipment of the vehicle therefore enables greater . loads than 7 tons to be carried within the 12-tons gross stipulated by the tyre rating of 2 tons per wheel, but if such heavier loads arc to be transported, it would be advisable to apportien them more towards the rear ash:, because of weight distribution.

The Eagle is essentially a trunknautage model, therefore I planned the day's trials to include a fair measure of main-road operation. As the tests were made in Surrey, there was relatively little level ground, but ample opportunity of assessing the merits of the constant-mesh gearbox. Because of its initial stiffness, the test vehicle was below its peak of efficiency, and it would require a considerably greater mileage to run it in fully, and to obtain the optimum in fuel economy.

-First, _an assault was made on Pebblecombe Hill, near Dorking, which was at one time used as a trials climb for cars., In its present made-up form the hill presents less hazardsto the motorist, but the I-in-6 gradient is sufficient to test the climbing ability of commercial vehicles. The Eagle performed well and there was plenty of reserve power to make a stop-start test without apprehension, the handbrake holding the chassis poised on the

gradient with relative ease while low gear was selected.

I stopped the vehicle at the top of the hill, with the front wheels turned on full lock, in preparation to negotiate the T junction. There might have been excuse if there had been wind-up in the transmission, when starting from rest, but the behaviour of the Eagle was again above reproach.

Braking 'characteristics were studied. when descending Box Hill at speed,.:full.use of. the friction facings being made in preference to employing the engine as a retarding,force.

The drums became well heated, but both hand and foot brakes remained effective and I was thus able to hold. the chassis comfortably wha reversing on the first hairpin bend. With a less marueuvrable vehicle, or one with poor braking, the turn might not have been so successfully accomplished.

Consumption trials were started from Holmwood, where the fuel tank was refilled and all other preparations made for a trunk-route test. I made no attempt to conserve fuel, observing a maximum speed of 30-35 m.p.h., which is quite a fast pace for a vehicle of the cruiser weight class. I always consider that drivers of Gardner-engined vehicles are different from their contemporaries, because if they are skilled they make use of the low-speed_ torque when driving, whereas others are apt to change gear to keep the engine in the higher range of its governed speed.

I therefore ran this trial employing the correct Gardner driving method and delayed changing to a lower gear until such time that almost every engine revolution could c6 be counted. Working to this rule, the overdrive gear and direct drive were used extensively, and there were only infrequent intervals where third gear was required. I formed the opinion during the time the vehicle was in my charge that the difference in ratio between direct drive and third is possibly too marked when employed with a power unit governed to 1,700 r.p.m.

Direct Drive Too Early At governed engine speed in third gear, the vehicle is travelling at 15 m.p.h., and with the decrease in speed caused by rolling resistance during unhurried gear changing, direct drive is brought into use at approximately 13-14 m.p.h. My driving experience of medium-weight vehicles, equipped with the 4LW unit, is restricted, and this apparent fault might be common to others of its class.

In other respects I place high value upon the Eagle for trunk haulage because it can maintain a fast pace when the occasion is presented, its stability and suspension are excellent, and the full torque from 1,000 r.p.m. permits flexible driving. Coyering the undulating road between Holmwood and Horsham, the fuel return was 13.2 m.p.g. for the complete out-and-return circuit, • including turning in a by-road at Horsham. This follows the general trend of Gardner-engine fuel economy, and with an overall running speed of 24.2 m.p.h. the Eagle would not be far behind its larger-engined contemporaries on a trunk route.

Although not s6 swift off the mark as its namesake, the M.T.N. Eagle has a surprising acceleration rate for a chassis of so moderate a power-toweight ratio, and relatively low governing of the engine speed. Apart from the lowest ratio, all other gears were employed during the acceleration trials, overdrive being engaged at 25 m.p.h. Undoubtedly, many seconds were saved during gear changing because of the constant-mesh facilities of the new Meadows box; there is little opportunity for the road speed to fall off when the clutch is disengaged.

Averages of the acceleration trials revealed that the Eagle could reach

20 m.p.h. from rest in 22.5 sees., and 30 m.p.h. in 47 secs. I could not measure the direct-drive performance from 10-30 m.p.h. because the road speed at governed engine revolutions was 25-26 m.p.h., and to attempt an overdrive test from 10 m.p.h. was impracticable in the stretch of level road .available. The high. standard of braking set by the preceding tests of the Rutland chassis was maintained in the Eagle, although extensive rear-wheel locking at 20 m.p.h. gave a false impression of the effect, as indicated by the 29-ft. stopping distance. Using the Webley marking device for noting the point where the brakes are

applied,.! have found a stopping distance of 50-55 ft. from 30 m.p.h. to be practically the best possible for a vehicle equipped with poweroperated or vacuum-assisted braking 'systems. The Eagle is one of , the vehicles which has helped to set this standard, the actual stopping distance from 30 m.p.h. being 56 ft.