Britain still leads in heavy transport design

Page 97

Page 98

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by Peter M. Yates

Group managing director, Atkinson Vehicles Ltd.

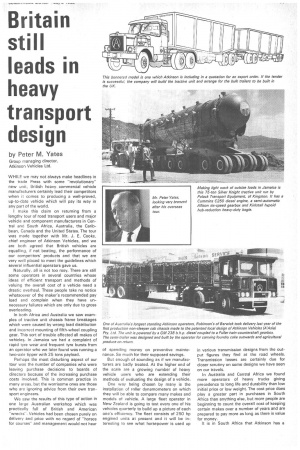

WHILE we may not always make headlines in the trade Press with some "revolutionary" new unit, British heavy commercial vehicle manufacturers certainly lead their competitors when it comes to producing a well-proved, up-to-date vehicle which will pay its way in any part of the world.

I make this claim on returning from a lengthy tour of road transport users and major vehicle and component manufacturers in Central and South Africa, Australia, the Caribbean, Canada and the United States. The tour was made together with Mr. J. E. Cooke, chief engineer of Atkinson Vehicles, and we are both agreed that British vehicles are equalling, if not beating, the performance of our competitors' products and that we are very well placed to meet the guidelines which several influential operators gave us.

Naturally, all is not too rosy. There are still some operators in several countries whose ideas of efficient transport and methods of valuing the overall cost of a vehicle need a drastic overhaul. These people take no notice whatsoever of the maker's recommended pay load and complain when they have unnecessary failures which are only due to gross overloading.

In both Africa and Australia we saw examples of tractive unit chassis frame breakages which were caused by wrong load distribution and incorrect mounting of fifth-wheel coupling gear. This sort of trouble affected all makes of vehicles. In Jamaica we had a complaint of rapid tyre wear and frequent tyre bursts from an operator who we later found was running a two-axle tipper with 25 tons payload.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of our tour was the number of companies who were leaving purchase decisions to boards of directors because of the increasing purchase costs involved. This is common practice in many areas, but the worrisome ones are those who are ignoring advice from their own transport engineers.

We saw the results of this type of action in one large Australian workshop which was practically full of British and American "wrecks-. Vehicles had been chosen purely on delivery and price with no regard of "horses for courses" and management would not hear

of spending money on preventive maintenance. So much for their supposed savings.

But enough of sounding as if we manufacturers are badly treated. At the higher end of the scale are a growing number of heavy vehicle users who are extending their methods of evaluating the design of a vehicle.

One way being chosen by many is the installation of roller dynamometers on which they will be able to compare many makes and models of vehicle. A large fleet operator in New Zealand is going to test every one of his vehicles quarterly to build up a picture of each one's efficiency. The fleet consists of 250 hp engined units at present and it will be in-, teresting to see what horsepower is used up in various transmission designs from the output figures they find at the road wheels. Transmission losses are certainly due for closer scrutiny on some designs we have seen on our travels.

In Australia and Central Africa we found more operators of heavy trucks giving precedence to long life and durability than low initial price or low weight. The cost price does play a greater part in purchases in South Africa than anything else, but more people are beginning to count the overall cost of keeping certain makes over a number of years and are prepared to pay more as long as there is value for money.

It is in South Africa that Atkinson has a good example of what is meant by durability and value for money. One of nine of our vehicles being used to carry cars over long distances from the 'Cape has come in for overhaul after covering 726,000 miles.

The crankshaft had no more than 0.001 wear and after liners and pistons etc. were fitted the vehicle went back into operation. It is interesting to note that neither the gearbox nor the double-helical rear axle had any work done on them at this stage and that with the replacement of bearings it should be possible to cover another 700,000 miles.

Some idea of what type of point can influence a vehicle purchase nowadays was gained from the chief buyer of a welkknown South African organization, who was looking for vehicles with power units of 250 hp upwards. They wanted their vehicles to pull away from traffic lights rapidly and average good speeds up gradients so that no other traffic was held up—their trucks are very conspicuous and they do not want any slight on their name.

Engine designs have been proved in varying climatic and operating conditions for some time, but -there is no getting away from increasing demands from all parts of the world for more power. But more power with a difference.

Many engine manufacturers are now concentrating on producing V as well as in-line units with flatter power curves, and high rise torque curves to allow the driver to stay in a higher gear longer and reduce the number of gear changes he has to make in his daily work. These engines will run at lower revs to give the dual benefits of longevity and low fuel consumption: it is interesting to note that the British manufacturer has usually based his designs on this premise for some years.

One interesting example of the "customtorque" engine being aimed at was a diesel which, for high speed or extra heavy haulage, could develop nearly 500 bhp at 2,100 rpm, with a maximum torque of 1,300 !bit. at 1,400 rpm. Normally, it would be de-rated to produce around 435 bhp and 1,200 lb.ft. and for the economically minded operator it could be supplied to produce 390 bhp at around 1,950 rpm and 1,140 lb.ft. maximum torque. As well as these outputs, engine manufacturers are aiming at a life which will be guaranteed for 300,000 miles under arduous operating conditions.

I mentioned chassis frames earlier and, despite some misuse, our designs are standing up to a variety of conditions and have the best combination of strength with low weight. Several American manufacturers have been working with aluminium alloys in order to reduce weight, but this has not proved successful on side-members in particular.

As far as sideand cross-members are concerned it would appear that the Americans are now on the right lines by moving to chrome manganese molybdenum steel with a yield strength in the region of 110,000 p.s.i. As the weight saved by using an aluminium frame and cross-members on a three-axle tractor is only in the region of 70 to 30Ib, it does not justify the additional expense and limitation in use.

Australia is also the birth-place of what I consider to be one of the finest of drivers' cabs ever built. The Atkinson organization there has produced a design especially for local conditions—a piece of equipment which needs to be designed individually for most overseas countries.

In its present form the Australian cab is an excellent base on which to carry out developments for several years. it has a simple, but very effective method of ventilation using ram effect from the vehicle's movement with the air being forced in from above the windscreen into the double-skin, which is thereby pressurized to give internal ventilation. While by UK standards the density of traffic on Australian roads is light, the road conditions are not as good and with dirt shoulders on most roads, stone damage to windscreens is a frequent occurrence. Because of this the cab has been produced in such a way that windscreens are easily replaced. As a design it is attractive from the view of both manufacturers and users and it could well prove to be welcome in many other countries besides Australia.

In New Zealand we are using a slightly different design for the cabs for Atkinson vehicles there which is produced using reinforced plastics mouldings with the cavity between the inner and outer shells filled with rigid polyurethane foam. The only parts which are not made locally are the door-handles. The mudguard skirts are also of plastics and the whole cab is three-point mounted on rubber buffers.

Cab framing generally has to be much stronger than in the UK, because of the amount of running over what can only be described as tracks. In Africa this can be standard .square sectioned tube and in other territories there are frames which are made up from rolled steel angle and which have proved to be robust enough for practically anything.

I must digress for a moment, while talking about cabs, in that 1 was rather surprised by the extent to which some USA manufacturers are going in meeting operators' requirements there. It is not unusual to see vehicles coming off the assembly line completely painted in the operators' colours and with up to $10,000 worth of "goodies", the latter being such extras as additional chrome plating, radio and even television.

An aspect of transport design in which British commercial vehicle manufacturers remain supreme is braking. We have had so much pressure exerted on us and have carried out so much research into the subject that we have gained quite a lead. On inspecting several American articulated outfits we came to the conclusion that we could only describe their braking arrangements as adequate and they have certainly not gone as far as developing effective parking arrangements.

In fact, we found some reluctance by manufacturers to commit themselves to frontwheel braking, the approach still being to let the trailer do most of the stopping. Wherever front-wheel brakes are fitted they tend to be as optional extras and have limiting valves to reduce their effect.

There will still be a need for multi-speed gearboxes, particularly from the operators on long-distance haulage over good roads on the trunking duties of Australia and Africa. Manufacturers are now working on designs covering six-, nine-, ten-, 13and 15-speed units, although the 10-speed would appear to meet the greater number of requests, and to cater for the extra heavy outfits, development work is being made on transmissions capable of taking up to 1,500 lb.ft. torque.

Talking of transmissions reminds me cf a rather impressive Japanese truck we saw in New Zealand, which gave us further food for thought on what type of competition we can expect. It was a model with a 240 hp twostroke engine similar to the GM 6.71. The cab was certainly impressive but the transmission seemed very light considering the potential torque range of its power-unit.

Our world tour emphasized how operators are becoming more specialized and demanding in their requirements and we are in no doubt that this will favour the small, independent makers. The British companies in this class are particularly well placed as they can build in and match a wide variety of first-quality major chassis components to the users' specialized needs.