Lorry Driving on the Roof of the World

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

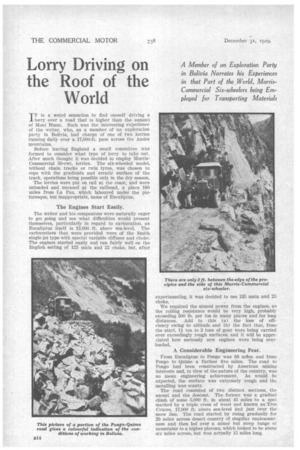

A Member of an Exploration Party in Bolivia Narrates his Experiences in that Part of the World, MorrisCommercial Six-wheelers being Emplayed for Transporting Materials

IT is a weird sensation to find oneself driving a lorry over a road that is higher than the summit of Mont Blanc. Such was the interesting experience of the writer, who, as a member of an exploration party in Bolivia, had charge of one of two lorries running daily over a 17,000-ft. pass across the Andes mountains.,

Before leaving England a small committee was formed to consider what type of lorry to take out. After much thought it was decided to employ MorrisCommercial 30-cwt. lorries. The six-wheeled model, without chain tracks or twin tyres, was chosen to cope with the gradients and erratic surface of the track, operations being possible only in the dry season.

The lorries were put on rail at the coast, and were unloaded and uncased at the railhead, a place 160 miles from La Paz, which laboured under the picturesque, but inappropriate, name of Eucaliptus.

The Engines Start Easily.

The writer and his companions were naturally eager to get going and see what difficulties would present themselves, particularly in regard to carburation, as Eucaliptus itself is 12,000 ft. above sea-level. The carburetters that were provided were of the Smith single-jet type with special variable diffuser and choke. The engines started easily and ran fairly well on the English setting of 125 main and 22 choke, but, after experimenting, it was decided to use 135 main and 25 choke.

We required the utmost power from the engines, as the rolling resistance would be very high, probably exceeding 500 lb. per ton in many places and for long distances. Add to this (a) the loss of efficiency owing to altitude and (b) the fact that, from the start, 11 ton to 2 tons of gear were being carried over .exceedingly rough surfaces, and it. will be appreciated bow seriously new engines were being overloaded.

A Considerable Engineering Feat.

From Eucaliptus to Pongo was 63 ables and from Pongo to Quiine a further five miles. The road to Pongo had been constructed by American mining interests and, in view of the nature of the country, was no mean engineering achievement. As would be expected, the surface was extremely rough and the metalling was scanty.

The road consisted of two distinct sections; the ascent and the descent. The former was a gradual climb, of some 5,000 ft. in about 45 miles to a spot marked by a triple cross of wood and known as Tres. 'Cruces, 17,000 ft. above sea-level and just over the snow line. The road started by rising gradually for 20 miles across desert country of singular impleasant7 ness and then led over a minor but steep range al: mountains to a higher plateau, which looked to he about six miles across, but was actually 15 miles long. ,Although by European standards it would he looked upon as dangerous, we soon became accustomed to this section. Besides the difficulty of gauging distances at great altitude, we .found that gradients both Up and dewn were much severer than they appeared, From Tres Cruces to Pongo the road dropped 5,500 ft. in 18 miles, with a further descent of 1,500 ft. in five miles to Quiche. The descent was noteworthy fOr the number, abruptness and steep gradients of the hair-pin bends, over many of which reversing was necessary. One consolation amidst the trials was that, when loaded, the lorries were tackling the comparatively gradual ascent, and were facing the severest climbs on the return journey when• travelling light.

Well Over 'Two Tons on One Lorry.

A typical example of a dity's w trunks Which haue to be lifted a The first trip was started about mid-day, one lorry carrying a lead of l ton, an assistant, beside the driver, and three others being perched aloft. The engine, being overloaded, had to be kept turning at high speed, and it was only for short periods that it was possible to engage tap gear. Nevertheless, in spite of the altitude and the low boiling point, the water in the radiator, did not

boil, not even on tie early trips, whi the bearings were stiff. All motor lorries, except those in the writer's part y, regularly carried a reserve supply of water, and they were often seen pulled in to• cool down.

The first section of the trip was but uneventful. At Caxata,an Indian village, half way, a halt was called in order tQ rest. Tres Cruces was reached as light failed. The descent, which was difficult enough in broad daylight and when accustomed to it, was an entirely diffefent proposition when undertaken in pitch darkness for the first time. With both headlights and a spotlight focused by the assistant it was possible to see the hair-pins in time.

A sharp increase in the gradient was apparent only by the lorry equally stddenly gathering momentum. As this occurred now and again, just before 180-degree bends, it will be understood how alert it was necessary to be. Often the sound of rukhing water would become apparent. In the darkness it sounded as if a deluge was being approached. Tile lights, however, showed a clear track* ahead and the lorries continued on their course, the noise increasing until it thundered overhead. It was one of many waterfalls close tb the road, but passing under it.

Heavy Rains Destroy the Road.

An of a sudden a splash of electric lights appeared 1,000 ft. below. This was Pongo, the white outpost in that .district, and the headquarters and rest camp of the American tin mines. A party had gone forward to study the possibilities of getting the lorries through to Quirae and beyond. A road to Quime had been under construction, but had not been completed. The extra heavy rains had made havoc of it and, over the greater part, had caused landslides. The local people were now making an effort to get the road ready for immediate use, and it appeared as if it would be pos

sible without unusual difficulty eventually to drive to Quime.

The report on the track after Quime wag entirely against even attempting to penetrate with wheeled transport. The rains had in parts practically obliterated the track, and it was a matter of arranging for mule trains to carry on the transport from QlliMQ to Our 'destination. This was, of course, a great disappointment, as the six-wheelers had been chosen with an eye to this section of the track.

The Loads Transferred to Mules.

.,A dump was promptly, organized at Pongo, where• the gear was unloaded, uncased, dismantled and reduced to mule loads. Meanwhile, the lorries were running to and from Eucaliptus, completing the job. The teltal weight. of our gear was about 40 tons: On the journey, back the steepness and difficulty Of the Climb to Tres Cruces completely offset the fact of cur traiel,litig..empty. The statement that the reduCtion gearbOx was in use over about a quarter of the climb and that On this section the ordinary first gear vittually functioned as top gear, will give some idea of the test to which these lorries were pat. In spite of their being empty, first gear was engaged and the throttle was kept wide open for six or sever' miles on end.

By the time all the material had been moved from Eucaliptus to Pongo the road to Quitne was ready for its baptism of wheeled transport. It was a repetition of the stretch from Tres Cruces to Pongo. There were three hair-pin .bends at a oonsiderable .angle and on these :the lorries had to be reversed. Going over

ark. Towing two stout tree portions where round as the bend is so acute, landslides had been cleared was like driving over a saturated ploughed field. There was ono particularly raudOy section which could be negotiated only in first reduction, a gear With an 83 to 1 ratio. At one point the road itself had slid away to the river Valley hnngreds of feet Mlow. This left no clearance on the safe side of the track and 2 ft. on the precipitous side,

An Extra Ton Towed by Each Lorry.

Variations in the routine were provided by putting additional load on the ever-willing,lorries. The party had Ingersolritand air compressors, which had been brought encased to Pongo. At this point they were stripped for the further journey. In this state they each weighed over t ton. They were unsprung, had iron-tyred wheels and very slight steering lock. One of them was towed. Half-a-dozen Indians .were carried to pull it around the bends. These Indians were carried in addition to the ordinary full load: and the compressor on tow. In this foamier four comPressors

were successfully mOved to Online. •

A farther diversion. Was provided on some of the journeys back from Qtlime. To help the local people, who were constructing a bridge, it was agreed halfWay back to Pongo to tow, a number of lusty tree trunks. It is placed on record that a trunk 26 ft. long was hitched to the tow, hook and moved thus.