EFFECTS of LOAD DISTRIBU1

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ON

on TYRE WEAR Studious Attention to An Important Tyrelife Factor Which Can Bring About

Useful Economies

How Better and Longer Service Can Be Obtained by Following the Sound Advice

of the Author

LOAD distribution has a great effect on tyre life. It is a point which, if studied and acted upon, can be made to show big economics. But it is no simple matter. There are so many influences to consider. Take bodies for instance; there are many types, and each throws different stress on the tyre equipment.

Type of control—normal, forward, etc.—must also be taken into account. These forward-control jobs throw far greater stress on the front tyres than do normal-control vehicles, not only because of the weight of engine and cab directly overhead, but also by reason of the front axle having to carry quite a substantial proportion of the actual load.

On many vehicles, the tyres, although apparently of adequate carrying capacity for the work in hand, are grossly overloaded individually. Or, again, owing to load distribution, the rear axle may be overloaded whilst the front axle is not, and vice versa.

Overcoming Rear-axle Overloads by Oversize Tyres

Rear-axle overloads are often overcome by fitting oversize tyres at the back. This sounds a simple way out of the difficulty, but it is not by any means free from snags. The rear end • of the vehicle, being slightly higher than the front, because of the oversize tyres, tends to increase the trouble known as " load transference." This has already been described in detail in a previous article.

It will be remembered that during the braking period there is a tendency for the weight of the load to pitch forward, so that in the act of slowing down the burden is shifted, to a large extent, from the back to the front axle. The slight forward tilt, which oversize rear tyres give to a vehicle, is inclined to increase the degree of load transference. This often results in rapid wear on the front tyres, due to repeated ,doses of temporary overloading.

• Thus, the economies effected by fitting larger tyres to the rear axle are, to some extent, offset by the slight increase in cost on the front. The obvious way out is to fit oversize front tyres as well, always provided that clearances will allow this to be done.

In order to check up the weight apportionment of the individual axles it is necessary that each should be weighed separately, at a time when the vehicle is carrying its oormal load. The resulting figures should be compared with the tyre-carrying capacity of each axle. It is no good comparing the total weight of vehicle and load with total carrying capacity of tyres because, as we have already seen, the tyres may not be carrying equal loads.

If actual weighing of the laden vehicle be not convenient the approximate axle loads can be calculated, provided that the separate empty axle weights are known, and provided that the pay-load can be estimated within reasonable limits.

Measure the distance from the centre of the front hub to the centre of the pay-load (A), then measure the distance from the centre of the back hub to the centre of pay-load (B). Finally, measure the distance from centre to centre of the front and rear hubs (C). These measurements should be taken in inches.

A — pay-load + rear-axle weight empty = total weight on rear tyres.

— x pay-load front-axle weight empty = total weight on front tyres. There are great individual differences even in the loads carried by tyres fitted to the same axle, particularly to those fitted to the rear axle. Moreover, the practice of running twin tyres at the rear is responsible for quite a few loading problems.

Road camber is one of the most common causes of unequal weight distribution.

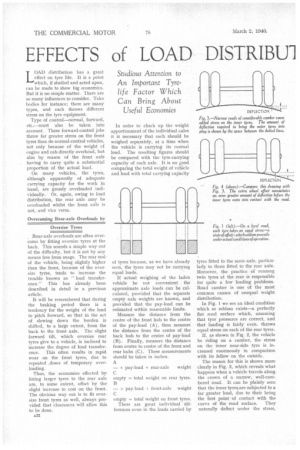

In Fig. 1 we see an ideal condition which so seldom exists—a perfectly flat road surface which, assuming that tyre pressures are correct, and that loading is fairly even, throws equal stress on each of the rear tyres. If, as shown in Fig. 2, the vehicle be riding on a camber, the stress on the inner near-side tyre is increased enormously in comparison with its fellow on the outside.

The reason for this is shown more

clearly in Fig. 3, which reveals what happens when a vehicle travels along the crown of a narrow, well-cam

bered road. It can be plainly seen that the inner tyrmare subjected to a far greater load, due to their being the first point of contact with the curve of the road surface. They naturally deflect under the stress, and this brings the outer tyres into contact with the road, although they are relieved of much of their due share of the work by the overloaded inner tyres. •

Too much wheel offset will cause even greater stress on the inner tyres when travelling along a cambered road. This can be more easily appreciated by a study of Figs. 3 and 4. The first sketch shows a rear-axle equipment with wheels of normal offset. For the purpose of illustration, no tyre deflection is shown, but the amount that the inner tyres will have to deflect before the outer tyres can touch the road is shown by the space between the dotted lines.

Fig. 4 shows the same tyres on the same camber, but with wheels of greater offset. It is obvious that the inner tyres will need to deflect even more before the outer tyres touch the road surface. Compare the necessary amount of deflection, as shown by the space between the dotted lines, with that of the previous sketch. This deflection represents overloading. It is no uncommon event for the inner tyres to carry two-thirds of the total back-axle load.

A theoretically perfect axle, from the tyre point of view, would be one which Was pivoted in the centre, as shown in Fig. 5. This would allow equal road contact of all tyres on cambered roads and would do much to equalize load distribution.

The theory can be carried even farther. A similar pivot could be arranged between each individual wheel, with some sort of limiting device to prevent rubbing of one tyre against the other. This arrangement would give equal tyre-to-road contact under practically all conditions. I am afraid, however, that it will never be more than a theory.

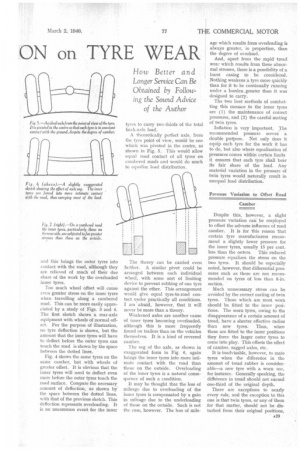

Weakened axles are another cause of inner tyres becoming overloaded, although this is more frequently found on trailers than on the vehicles themselves. It is a kind of reversed camber.

The sag of the axle, as shown in exaggerated form in Fig. 6, again brings the inner tyres into more intimate contact with the road than those on the outside. Overloading of the inner tyres is a natural consequence of such a condition.

It may be thought that the loss of mileage due to overloading of the inner tyres is compensated by a gain in mileage due to the underloading of those on the outside. Such is not the case, however. The loss of mile

age which results from overloading is always greater, in proportion, than the degree of overload.

And, apart from the rapid tread wea...which results from these abnormal stresses, there is a possibility of a burst casing to be considered. Nothing weakens a tyre more quickly than for it to be continually running under a burden_ greater than it was designed to carry.

The two best methods of combatting this menace to the inner tyres are (1) the maintenance of correct pressures, and (2) the careful mating of twin tyres.

Inflation is very important. The recommended pressure serves a double purpose. Not only does it equip each tyre for the work it has to do, but also where equalization of pressures comes within certain limits it ensures that each tyre shall bear its fair share of the load. Any material variation in the pressure of twin tyres would naturally result in unequal load distribution.

Pressure Variation to Offset Road Camber Despite this, however, a slight pressure variation can be employed to offset the adverse influence of road camber. It is for this reason that certain tyre manufacturers recommend a slightly lower pressure for the inner tyres, usually 15 per cent. less than the outers. This reduced pressure equalizes the stress on the two tyres. It should be especially noted, however, that differential pressures such as these are not recommended on tyres of less than 8-in. section.

Much unnecessary stress can be avoided by the correct mating of twin tyres. Those which are most worn should be fitted to the inner positions. The worn tyres, owing to the disappearance of a certain amount of tread, have a shorter effective radius than new tyres. Thus, when these are fitted to the inner positions they force the larger outer tyres to come into play. This offsets the effect of camber, sagged axles, etc.

It is inadvisable, however, to mate tyres when the difference in the amount of tread rubber is considerable—a new tyre with a worn one, for instance. Generally speaking, the difference in tread should not exceed one-third of the original depth.

There are exceptions to nearly every rule, and the exception to this one is that twin tyres, or any of them for that matter, should not be disturbed from their original positions,

except to correct certain forms of irregular wear.

After a few thousand miles a tyre ". beds itself in," it adjusts itself to its fellow, so that each is doing its fair share of the work. It is probable that during the bedding-down period the one tyre has been overloaded, owing -to one or other of the various causes already considered.

This has caused it to wear rapidly for the first month or so, and has thus brought it down to an equal footing with its twin. From that moment the tyres will have to do equal work. But, if their position be changed, they will have to start adjusting

themselves to each other again, and rapid wear will take pliace during the process.

Bearing on the same subject, it will be noticed by many operators that there is a tendency, more noticeable on passenger-carrying than on goods vehicles, for the front tyres to wear more rapidly on one side of the tread than on the other. In fact, the tread will wear quite smooth on one shoulder and yet have plenty of pattern left on the other.

There is a strong temptation to reverse the tyre to correct the uneven wear, but this is quite the wrong thing to do. The tyre has worn in

this way because it has adjusted itself to the camber of the road and to certain mechanical characteristics of the vehicle.

At first, the wear was probably very rapid, because the tyre was riding "on edge" as it were. Eventually, however, it wears down until the full width of tread is called into play, with a corresponding slowingdown in the rate of wear. If the operator yields to temptation, and reverses the tyre in order to secure even wear, he will start it riding on edge again, but even worse than before. And the rate of wear wilt be

rapid. L V. B