STEADY AS SHE GOES

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Any road accident involving an HGV is liable to be serious: if a petrol tanker is involved it could be a nightmare. The German TOPAS project aims to minimise the risks.

II Nothing focuses attention on safety quite like a fatal accident. Sadly it often seems as if a tragedy is the only guaranteed way of blowing legislators off the fence in order to make more effective safety laws.

The road transport industry is one area where this "knee-jerk" approach to safety is all-too-often applied. It was the horrific coach crash on the M6 in 1985, in which 13 people died, that finally forced the Department of Transport to start down the road leading to the current legislation on PSV speed limiters.

More recently, the spate of accidents on sections of motorways under repair has also forced the DTp to introduce a mandatory (rather than advisory) 80km (50mph) speed limit in contraflows.

While attempts to prevent these kind of accidents from ever happening again is undoubtedly praiseworthy, it is hard to see post-accident legislation as anything other than closing the stable door after the horse has bolted.

Although there are a number of laws and regulations governing the construction and use of road tankers, the day-to-day operational safety of such vehicles is, quite rightly, generally left in the hands of operators. So far this arrangement appears to work well in the UK, where road tankers — particularly those carrying petroleum products — have a good safety record.

Nothing, however, is perfect. Last year's tanker crash at Herborn in West Germany, which sent a fireball racing through the small town, once again reminded industry critics of the dangers involved in transporting highly inflammable products by road. It was only the quick reactions of the emergency services which helped prevent a potential disaster last month when a 38-tonne artic tanker overturned in Walton-on-Thames, Surrey, spilling thousands of litres of fuel and causing a major evacuation.

One truck manufacturer which has been actively looking at ways of improving road tanker safety is Daimler-Benz. In 1981 it began work on a project with the German trailer builder Haller, fluid management specialist Schwelm, and Raab Karcher — a German-based road tanker operator with over 700 vehicles.

The roots of the project go back to 1978 when a study was made into a number of tanker accidents in Germany.

Using this research, Daimler-Benz and Haller, aided by a grant of nearly 22 million from the German Federal Ministry of Research and Technology, set out to improve vehicle stability.

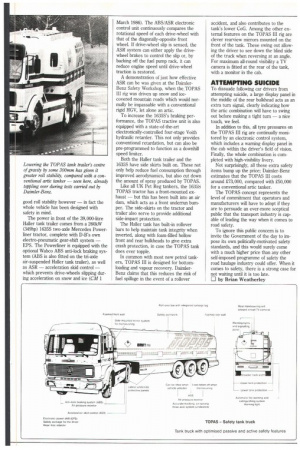

The result was TOPAS — Tank truck with Optimised Passive and Active Safety features.

In order to tackle the problem of overturning vehicles Haller followed the same route as many UK tipping trailer builders, by reducing the overall centre of gravity of the semi-trailer. For TOPAS I Haller adopted a new shape of tank which, with wider track axles (2,100mm instead of 2,040mm) and low-profile 70% aspect ratio tyres located at the maximum outer dimension of 2.5 metres, allowed the tank trailer's centre of gravity to be lowered by approximately 300mrn, compared with standard designs.

FRANKFURT SHOW

The TOPAS 1 tank trailer was first shown by Haller at the 1985 Frankfurt Show, and has been running in Raab Karcher's fleet ever since.

The process of refining the TOPAS concept has continued unabated. A TOPAS II made its debut at the end of 1986, coinciding with European Road Safety Year, and the latest TOPAS III version was revealed this January at a Daimler-Benz Commercial Vehicle Safety Workshop in Switzerland.

Reducing the artic tanker's CoG has clearly given TOPAS the edge in roll stability over a conventional design. Daimler-Benz has carried out roll-over tests using a track which reproduces the kind of narrow, sharply-curving bends commonly found on autobahn exit slip roads. TOPAS is capable of safely negotiating such roads at speeds of around 40km/h (24mph), while at similar speeds the semi-trailer of a conventional artic tanker starts to roll past the point of no return. Indeed, only by fitting special outriggers to the conventional or "control" rig, did Daimler-Benz prevent it from toppling over completely.

There is a lot more to TOPAS than good roll stability however — in fact the whole vehicle has been designed with safety in mind.

The power in front of the 39,000-litre Haller tank trailer comes from a 260kW (349hp) 1635S two-axle Mercedes Powerliner tractor, complete with D-B's own electro-pneumatic gear-shift system — EPS. The Powerliner is equipped with the optional Wabco ABS anti-lock braking system (ABS is also fitted on the tri-axle air-suspended Haller tank trailer), as well as ASR — acceleration skid control — which prevents drive-wheels slipping during acceleration on snow and ice (CM 1 March 1986). The ABS/ASR electronic control unit continuously compares the rotational speed of each drive-wheel with that of the diagonally-opposite front wheel. If drive-wheel slip is sensed, the ASR system can either apply the drivewheel brakes to control the slip or, by backing off the fuel pump rack, it can reduce engine speed until drive-wheel traction is restored.

A demonstration of just how effective ASR can be was given at the DaimlerBenz Safety Workshop, when the TOPAS III rig was driven up snow and icecovered mountain roads which would normally be impassable with a conventional rigid HGV, let alone an artic.

To increase the 1635S's braking performance, the TOPAS tractive unit is also equipped with a state-of-the-art electronically-controlled four-stage Voith hydraulic retarder. This not only provides conventional retardation, but can also be pre-programmed to function as a downhill speed limiter.

Both the Haller tank trailer and the 16358 have side skirts built on. These not only help reduce fuel consumption through improved aerodynamics, but also cut down the amount of spray produced by TOPAS.

Like all UK Pet Reg tankers, the 1635S TOPAS tractor has a front-mounted exhaust — but this has been built into an air dam, which acts as a front underrun bumper. The side-skirts on the tractor and trailer also serve to provide additional side-impact protection.

The Haller tank has built-in rollover bars to help maintain tank integrity when inverted, along with foam-filled hollow front and rear bulkheads to give extra crash protection, in case the TOPAS tank does ever topple.

In common with most new petrol tankers, TOPAS III is designed for bottomloading and vapour recovery. DaimlerBenz claims that this reduces the risk of fuel spillage in the event of a rollover

accident, and also contributes to the tank's lower CoG. Among the other external features on the TOPAS III rig are clever rearview mirrors mounted on the front of the tank. These swing out allowing the driver to see down the blind side of the truck when reversing at an angle. For maximum all-round visibility a TV camera is fitted at the rear of the tank, with a monitor in the cab.

ATTEMPTING SUICIDE

To dissuade following car drivers from attempting suicide, a large display panel in the middle of the rear bulkhead acts as an extra turn signal, clearly indicating how the artic combination will have to swing out before making a tight turn — a nice touch, we feel.

In addition to this, all tyre pressures on the TOPAS III rig are continually monitored by an electronic control system, which includes a warning display panel in the cab within the driver's field of vision. Finally, the whole combination is completed with high-visibility livery.

Not surprisingly, all these extra safety items bump up the price; Daimler-Benz estimates that the TOPAS III costs around £73,000, compared with £50,000 for a conventional artic tanker.

The TOPAS concept represents the level of commitment that operators and manufacturers will have to adopt if they are to persuade an ever-more sceptical public that the transport industry is capable of leading the way when it comes to road safety.

To ignore this public concern is to invite the Government of the day to impose its own politically-motivated safety standards, and this would surely come with a much higher price than any other self-imposed programme of safety the road haulage industry could offer. When it comes to safety, there is a strong case for not waiting until it is too late.

0 by Brian Weatherley