TANKS TAK TO THE SKY

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

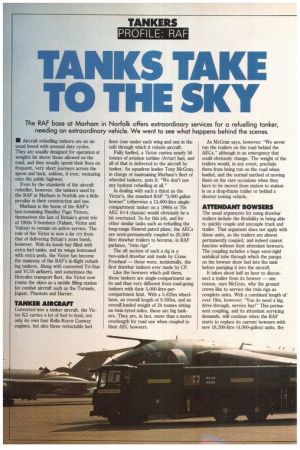

The RAF base at Marham in Norfolk offers extraordinary services for a refuelling tanker, needing an extraordinary vehicle. We went to see what happens behind the scenes.

• Aircraft refuelling tankers are an unusual breed with unusual duty cycles. They are usually designed for operation at weights far above those allowed on the road, and they usually spend their lives on frequent, very short journeys across the apron and back, seldom, if ever, venturing onto the public highway.

Even by the standards of the aircraft refueller, however, the tankers used by the RAF at Marham in Norfolk are a little peculiar in their construction and use.

Marham is the home of the RAF's last-remaining Handley Page Victors, themselves the last of Britain's great trio of 1950s V-bombers (Valiant, Victor and Vulcan) to remain on active service. The role of the Victor is now a far cry from that of delivering Britain's atom bomb, however. With its bomb bay filled with extra fuel tanks, and its wings festooned with extra pods, the Victor has become the mainstay of the RAF's in-flight refuelling tankers. Along with converted Tri-Star and VC10 airliners, and sometimes the Hercules transport fleet, the Victor now roams the skies as a mobile filling station for combat aircraft such as the Tornado, Jaguar, Phantom and Harrier.

TANKER AIRCRAFT

Converted into a tanker aircraft, the Victor 1(2 carries a lot of fuel to feed, not only its own four Rolls-Royce Conway engines, but also three retractable fuel lines (one under each wing and one in the tail) through which it refuels aircraft.

Fully fuelled, a Victor carries nearly 56 tonnes of aviation turbine (Avtur) fuel, and all of that is delivered to the aircraft by tanker. As squadron leader Tony McGran, in charge of maintaining Marham's fleet of wheeled tankers, puts it: "We don't use any hydrant refuelling at all."

In dealing with such a thirst as the Victor's, the standard RAF "3,000 gallon bowser" (otherwise a 13,600-litre singlecompartment tanker on a 1960s or 70s AEC 6x4 chassis) would obviously be a bit overtaxed. So for this job, and for other similar tasks such as refuelling the long-range Nimrod patrol plane, the AECs are semi-permanently coupled to 20,500litre drawbar trailers to become, in RAF parlance, "twin rigs".

The aft section of such a rig is a two-a)ded drawbar unit made by Crane Fruehauf — these were, incidentally, the first drawbar tankers ever made by CF.

Like the bowsers which pull them, these tankers are single-compartment units and thus very different from road-going tankers with their 5,000-litre-percompartment limit. With a 5.825m wheelbase, an overall length of 9.595m, and an overall loaded weight of 24 tonnes sitting on twin-tyred axles, these are big tankers. They are, in fact, more than a metre overlength for road use when coupled to their AEC bowsers. As McGran says, however: "We never run the trailers on the road behind the AECs," although in an emergency that could obviously change. The weight of the trailers would, in any event, preclude them from being run on the road when loaded, and the normal method of moving them on the rare occasions when they have to be moved from station to station is on a drop-frame trailer or behind a shorter towing vehicle.

ATTENDANT BOWSERS

The usual arguments for using drawbar trailers include the flexibility in being able to quickly couple and uncouple truck and trailer. That argument does not apply with these units, as the trailers are almost permanently coupled, and indeed cannot function without their attendant bowsers. The coupling includes a huge semi-rigid umbilical tube through which the pumps on the bowser draw fuel into the tank before pumping it into the aircraft.

It takes about half an hour to disconnect a trailer from its bowser — one reason, says McGran, why the ground crews like to service the twin rigs as complete units. With a combined length of over 19m, however: "You do need a big, drive-through, service bay!" This permanent coupling, and its attendant servicing demands, will continue when the RAF starts to replace its current bowsers with new 18,200-litre (4,000-gallon) units, the first of which should enter service soon.

Servicing is, of course, not a huge problem with these vehicles, simply because of the extremely limited distances which they cover each year. "1 suppose they do less than 5,000 miles (8,000km) a year, and they are likely to have a 15-year service life," says McGran.

One of the ways in which the life of a tanker on Victor-refuelling duties differs from that of ordinary airport tankers is that it can spend a lot of its life unloading aircraft rather than loading them. The amount of fuel required for each mission is carefully calculated, and it would obviously be wasteful to haul more than is necessary into the air. So if a Victor is on standby, as a backup to other aircraft, it may have its fuel load altered several times during the day so that it will be at the right weight for each mission.

PARENT BOWSER

As with loading fuel onto an aircraft, all necessary unloading is done via the parent bowser unit, with fuel being pumped back into the tanker trailer.

Unlike civilian road tankers, the RAF refuelling tankers rarely have a change in load type. Most service aircraft run on the same Avtur fuel, so flushing out to change fuel type is rare.

Apart from their plated weights, big compartments and specially-selected drab green paint finish, these tankers are surprisingly similar to ordinary civilian units. They are of welded aluminium construction, elliptical in cross-section, with internal baffles every 1.5m.

There is a top filling hatch and the discharge and refilling port is underneath at the front. They are fitted with microswitch-activated interlocks which prevent them from being moved while the hoses are connected to aircraft, and there are the usual safety lines to prevent discharges of static electricity.

They lead sheltered Lives, but the hundreds of tonnes of fuel moved every week are vital to keep the airforce fl • by