With Nationalization Ahead )

Page 46

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Eyes are Turning to

PRIVATE HIRE SOLVING THE PROBLEMS OF THE CARI6ER

HAVE just received a letter from a large coach operator. 1 The writer, whilst he approves of the principles laid down

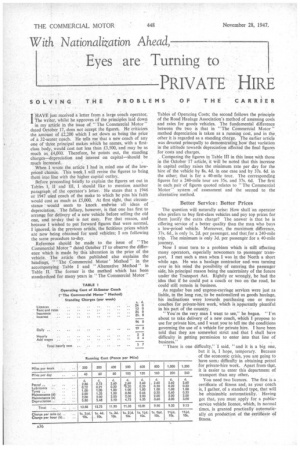

in my article in the issue of "The Commercial Motor' dated October 17, does not accept the figures. He criticizes the amount of £2,200 which I set down as being the price of a 32-seater coach. He tells me that a new coach of any one of three principal makes which he names, with a firstclass body, would cost not less than £3,500, and may be as much as £4,000. Therefore, he points out, the standing charges-depreciation and interest on capital-should be much increased.

When I wrote the article I had in. mind one of the lowpriced chassis. This week I will revise the figures to bring, them into line with the higher capital outlay.

Before proceeding briefly to explain the figures set out in Tables I, 11 and III, I should like to mention another paragraph of the operator's letter. He states that a 1946 or 1947 used coach of the make to which he pins his faith would cost as much as £5,000. At first sight, that circumstance would seem to knock endwise all ideas of depreciation. The fallacy, however, is that one has first to arrange for delivery of a new vehicle before selling the old one, and to-day that is not easy. For that reason, and because I wished to put forward figures that were normal, I ignored, in the previous article, the fictitious prices which are now being obtained for used vehicles; I am following the same procedure to-day. Reference should be made to the issue of " The Commercial Motor" dated October 17 to observe the difference which is made by this alteration in the price of the vehicle. The article then published also explains the headings, " ' The Commercial Motor' Method " in the accompanying Table I and "Alternative Method" in Table II. The former is the method which has been standardized for many years in " The Commercial Motor" Tables of Operating Costs; the second follows the principle of the Road Haulage Association's method of assessing costs and rates for goods vehicles. The fundamental difference between the two is that in "The Commercial Motor" method depreciation is taken as a running cost, and in the other it is regarded as a standing charge. The earlier article was devoted principally to demonstrating how that variation in the attitude towards depreciation affected the final figures for costs and charges.

Comparing the figures in Table III in this issue with those in the October 17 article, it will be noted that this increase in capital outlay raises the minimum rate per day for the hire of the vehicle by 8s. 4d. in one case and by 37s. 6d. in the other; that is for a 40-mile tour. The corresponding figures for a 240-mile tour are 35s. and 37s. 6d. The first in each pair of figures quoted relates to "The Commercial Motor" system of assessment and the second to the alternative method.

Better Service : Better Prices

The question will naturally arise: How shall an operator who prefers to buy first-class vehicles and pay top prices for them justify the extra charge? The answer is that he is offering service of a better quality than the man who buys a low-priced vehicle. Moreover, the maximum difference, 37s. 6d., is only Is. 2d. per passenger, and that for a 240-mile trip. The minimum is only 3d. per passenger for a 40-mile journey.

Now I must turn to a problem which is still affecting many operators, especially newcomers to passenger transport. I met such a man when I was in the North a short while ago. He was a haulage contractor and was turning over in his mind the possibility of entering the passenger side, his principal reason being the uncertainty of the future under the Transport Act. Rightly or wrongly, he had the idea that if he could put a coach or two on the road, he could still remain in business.

As regular bus and express-carriage services were just as liable, in the long run, to be nationalized as goods haulage, his inclinations were towards purchasing one or more coaches for private-hire work, which is apparently plentiful in his part of the country.

" You're the very man I want to see," he began. "I'm about to take delivery of a new coach, which I propose to use for private hire, and I want you to tell me the conditions governing the use of a vehicle for private hire. I have been told that they are somewhat strict and that I shall have difficulty in getting permission to enter into that line of business."

"There is one difficulty," I said, "and it is a big one, but it is, I hope, temporary. Because of the economic crisis, you are going to have soma difficulty in obtaining petrol for private-hire work. Apart from that, it is easier to enter this department of

1,000 1,200

transport than any other. .

You need two licences. The first is a certificate of fitness and, as your coach is, I gather, of a standard type, that will be ,obtainable automatically. Having got that, you must apply for a publicservice vehicle licence, which, in normal times, is granted practically automatically on productiod of the certificate of fitness. " And having got that P.S.V. licence," he said, "can I use the c6ach for any sort of passenger carrying? "

"You cannot," I said. "On the contrary, you may use it only for contract hire work. If you want to run bus or express services, or excursions and tours, you must obtain a road service licence from the Area Licensing Authority. and that is just as difficult as securing an A or B licence for goods vehicles, and I suppose you know something about that?"

"I do, indeed," he said, "and I am a bit worried at your statement that I may not run excursions and tours. That, surely, is the sort of work that a contract coach is to be used for?"

"The differences between contact work and excursions and tours have been set out in detail on many occasions by 'The Commercial Motor,' and as recently as June 'of this year," I replied, trying not to appear censorious. "In the first place, a contract carriage may not be used to carry passengers at separate fares."

"Well, that's all right," he said; "it should be easy to get around that."

"Now you've let yourself in for a full and detailed explanation, which will show you that you can't get around that," I rejoined. "In order to be sure that you do not let your contract carriage in any way except, for hire as a whole, and not for carrying passengers at separate fares, there are no fewer than seven conditions with which you must comply every time you hire out your coach. "First, the arrangements for bringing together all the passengers for the purpose of making the journey as a party must not be made by the holder of the public service vehicle licence, a person acting on his behalf or one who receives remuneration in respect of the arrangements," "Does it mean," he asked, "that John Smith in the High Road, the booking agent, can't get together a party and hire my vehicle for its conveyance?"

"Well, what about the secretary of the local Liberal Club? He usually arranges one or two parties during the summer and, as he is a pal of mine, I have been reckoning on getting business from him. Would it be all right for me to take an order from him?"

"Yes, I should say so," "But he receives remuneration. He is paid as secretary of the club."

" And does he receive any extra pay for arranging these parties? "

"No, I shouldn't think so' " In that case, it would be all right."

"Now," I said, "let's get on to the second conditioa. The journey must be made without previous notice to the public of these arrangements."

"Well, that's done it. That wipes out this Liberal CIO affair."

"Why does it?" I asked.

"Well, he always puts up a notice in the club for some weeks beforehand. That's how he gets the party together. Doesn't that come under the heading of previous notice to the public? " ' "In a sense, maybe, it does, but it is not, I imagine, the kind of notice to which this clause refers. You see, it is not really a notice to the public; it is a private announcement to the members of the club. Acts of Parliament are not, in my experience, generally framed to be unreasonable, and obviously you cannot arrange a party of this kind without some sort of announcement."

"Then there are works bean-feasts," he went or!. "There is usually quite a number of these at the varioun factories in the district. There, again, the man who organizes the party usually gets the people together by putting a notice in the workshops. Is that all right?."

".1 should say so.

".The next condition," I continued, "is that all the passengers must be carried to or in the vicinity of the proper destination of the journey."

"Are they very strict about that?" he asked.

" Well, reasonably strict, of course," I said.

Dropping Passengers Near Their Homes " Well, there is just this," he went on. "Asa rule when we are getting back at night, we pass near the homes of some of the members of the party before we reach the finishing point, and those in the outer districts like to be set down. Would that be all right? "

"Certainly. The clause stipulates only that the passengers must he carried to the vicinity of the destination and, in the case of a tour, the greater part of the journey. These conditions would be fulfilled for the passengers you have in mind."

"That's all right, then,he said. "What next?"

"!There must be no differentiation of fares. That,' I said, "emphasizes what I told you in the beginning—that the passengers must not be carried for separate fares. The coach must be hired as a whole."

"Well, I don't see any difficulty about that," he said. "Obviously, if the coach is going to be hired in the way you say it must be hired, I can't make any difference as between one and another, because I don't collect the fare3" "In the case of a journey to a particular destination, the passengers must not include any person who frequently, as a matter of routine, makes that journey," I continued.

"I don't see how I can do anything about that," he objected. • "I can't tell if one of the party is in the habit of regularly travelling on that route, and I can't see how I could find out."

"There, again, I think you can take it that the application of that clause will be reasonable. If it is a bona-fide party, the particular person who travels that -way regularly is actually a member of the party and the question is, hardly likely to arise: S.T.R. (To be continued.)