Attractive Features of

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

MODERN VANS

THERE is no stagnation in the design ol the van body. New styles are continually being evolved which combine utility with a smart appearance. One of the factors which promotes so much activity in van design is the variation of the steering position. Apart from the conventional position behind the engine, there are different types of forward control which influence the layout of the cab owing to the disposition of the front axle.

The bottom of the driver's door may be in front, behind, or mainly above the wheel-arch. A well-setback front axle is utilized to afford a step-in entrance in front of the wheel, or it has the effect of isolating the engine and bonnet in a forward position, thus im

proving greatly the accessibility.

A stylish cab gives character to the most box-like loading portion. The introduction of the sloping windscreen has been valuable in this connection. The sloping line is emphasized if the front line of the door be a continuation of it. This style of front is not confined to the normalcontrol cab, but has also been adopted with forward steering.

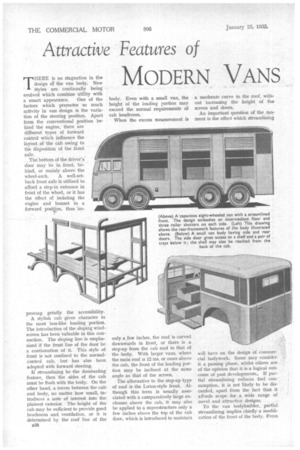

If streamlining be the dominating feature, then the sides of the cab must be flush with the body. On the other hand, a recess between the cab and body, no matter how small, introduces a note of interest into the plainest exterior. The height of the cab may be sufficient to provide good headroom and ventilation, or it is determined by the roof line of the n28 body. Even with a small van, the height of the loading portion may exceed the normal requirements of cab headroom.

When the excess measurement is only a few inches, the roof is curved downwards in front, or there is a step-up from the cab roof to that of the body. With larger vans, where the main roof is 12 ins, or more above the cab, the front of the loading portion may be inclined at the same angle as that of the screen.

The alternative to the step-up type of roof is the Luton-style front. Although this term is usually associated with a comparatively large enclosure above the cab, it may also be applied to a superstructure only a few inches above the top of the cab door, which is introduced to maintain

a moderate curve to the roof, without increasing the height of the) screen and doors.

An important question of the moment is the effect which streamlining will have on the design of commercial bodywork. Some may consider it a passing phase, whilst others are of the opinion that it is a logical outcome of past developments.. If partial streamlining reduces fuel consumption, it is not likely to be discarded, apart from the fact that it aff9rds scope for a wide range of novel and attractive designs.

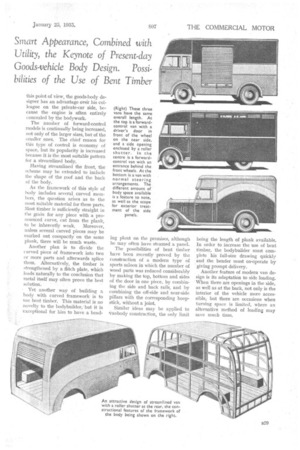

To the van bodybuilder, partial streamlining implies chiefly a modification of the front of the body. From this point of view, the goods-body designer has an advantage over his colleague on the private-car side, because the engine is often entirely concealed by the bodywork.

The number of forward-control models is continually being increased, not only of the larger sizes, but of the smaller ones. The chief reason for this type of control is economy of space, but its popularity is increased because it is the most suitable pattern for a streamlined body.

HaVing streamlined the front, the scheme may be extended to include the shape of the roof and the back of the body.

As the framework of this style of body includes several, curved members, the question arises as to the most suitable material for these parts. Most timber is sufficiently straight in the grain for any piece with a proaounced curve, cut from the plank, to be inherently weak. Moreover, unless several curved pieces may be marked out compactly. on the same plank, there will be much waste.

Another plan is to divide the curved piece of framework into two or more parts and afterwards splice them. Alternatively, the timber is strengthened by a flitch plate, which leads naturally to the conclusion that metal itself may often prove the best solution.

Yet another way of building a body with curved framework is to use bent timber. This material is no novelty to the bodybuilder, but it is exceptional for him to have a bend

ing plant on the premises, although he may often have steamed a panel.

The possibilities of bent timber have been recently proved by the construction of a modern type of sports saloon in which the number of wood parts was reduced considerably by making the top, bottom and sides of the door in one piece, by combining the side and back rails, and by combining the off-side and near-side pillars with the corresponding hoopstick, without a joint.

Similar ideas may be applied to 1-7anbody construction, the only limit

being the length of plank available. In order to increase the use of bent timber, the bodybuilder must complete his full-size drawing quickly and the bender must co-operate by giving prompt delivery.

Another feature of modern van design is its adaptation to side loading. When there are openings in the side, as well as at the back, not only is the interior of the vehicle more accessible, but there are occasions when turning space is limited, where an alternative method of loading may save much time.