Maximum service minimum responsibility

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

BY S. BUCKLEY

Assoc Inst T

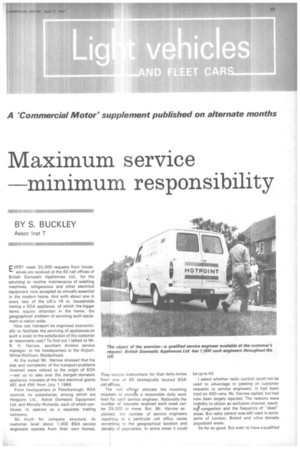

EVERY week 25,000 requests from house' wives are received at the 60 call offices of British Domestic Appliances Ltd., for the servicing or routine maintenance of washing machines, refrigerators and other electrical equipment now accepted as virtually essential in the modern home. And with about one in every two of the UK's 16 m, households having a BDA appliance, of which the bigger items require attention in the home, the geographical problem of servicing such equip

ment is nation-wide. • How can transport be organized economically to facilitate the servicing of appliances on such a scale to the satisfaction of the customer at reasonable cost? To find out I talked to Mr. R. H. Harrow, southern division service manager, at his headquarters at the Airport, White Waltham, Maidenhead.

At the outset Mr. Harrow stressed that the size and complexity of the transport problems involved were related to the origin of BDA —set up to take over the merged domestic appliance interests of the two electrical giants AEI and EMI from July 1 1966.

From headquarters at Peterborough, BDA controls its subsidiaries, among which are Hotpoint Ltd., Astral Domestic Equipment Ltd. and Morphy-Richards, each of which continues to operate as a separate trading company.

So much for company structure. At customer level about 1,000 BDA service engineers operate from their own homes. They receive instructions for their daily duties from one of 60 strategically located BDA call offices.

The call offices allocate the incoming requests to provide a reasonable daily work load for each service engineer. Nationally the number of requests received each week can be 25,000 or more. But, Mr. Harrow explained, the number of service engineers reporting to a particular call office varies according to the geographical location and density of population. In some areas it could be up to 40.

I asked whether radio control could not be used to advantage in passing on customer requests to service engineers. It had been tried on 400 vans, Mr. Harrow replied, but had now been largely rejected. The reasons were inability to obtain an exclusive channel, result ing and the frequency of "dead" areas. But radio control was still used in some parts of London. Bristol and other densely populated areas.

So far so good. But even to have a qualified service engineer available on call virtually anywhere in the UK is not enough. He must have with him a full range of spare parts.

Mr. Harrow told roe that nearly £1 m. of spares are held at White Waltham. Similar stocks are held at Lutterworth for the Midland division, with large stocks at Northallerton. Bonnybridge and Manchester for the Northern division. It is a separate transport exercise undertaken by their larger commercial vehicles to maintain these divisional stocks. From these stock warehouses spares are delivered to the service engineers either at their homes or to an agreed point so that their basic stocks are maintained and exceptional demands met.

Expensive specialists

In determining their overall transport policy to meet the demands of the servicing divisions. Mr. Harrow said that at the forefront of their minds was the fact that their service engineers were specialists and correspondingly expensive. Any ineffective time caused through nonavailability of a vehicle had to be avoided at all costs. If a .service engineer's van was idle there was a direct loss of about £8 a day in a man's time and a real, if unquantifiable loss resulting from customer dissatisfaction.

This prime requirement of maximum availability conditioned their thinking on vehicle selection and maintenance policy.

Although a fleet of 1,000 vehicles must obviously give rise to many problems, Mr. Harrow said that they had access to comprehensive records of operation under their own particular conditions which provided a reliable guide to their initial choice of vehicles.

In this context, Mr. Harrow doubted the validity of operational records unless they were on the scale of 100 vehicles or more operating over a three-year period. He felt there were so many possible variables to confuse the issue when comparing records that results obtained from relatively small numbers of vehicles over shorter periods than the one they used could be misleading.

From their records they had chosen Ford vans as most suitable for their requirements. Originally these were in the 10/12 cwt. category. But since their introduction just over a year ago they had been using Ford Transit 12 cwt. vans and practically the whole of their fleet was of Ford manufacture with an increasing proportion of Transits. While appreciating the value of standardization, I suggested to Mr. Harrow that with such large numbers involved there could be an opportunity to try out a batch of alternative makes or types of van so as to confirm, or otherwise, that the choice of vehicle was correct. He replied that they had in fact done just that only to find that on the score of insufficient evidence the results obtained were not sufficiently conclusive to warrant a major change.

Variable results

He could not stress too strongly the almost fortuitous differences which could arise between the results obtained from even identical vehicles with successive chassis numbers because of differences in driving techniques, local operational conditions and other reasons. Not only were the several reasons variable in themselves but the permutation of all possible factors, some advantageous and some otherwise, could in the two extremes result in wide variation which often did not permit rational and analytical explanation.

However, having made a careful study of their records for the whole of this large fleet of vans over a period of several years, Mr. Harrow said that they had come to the conclusion that the most economic period on which to base their vehicle replacement policy was approximately 3-+ years. Under normal conditions this amounted to about 45,000 miles based on a service engineer's weekly mileage of about 300.

From their extensive records they had found that beyond that period maintenance costs began to increase substantially. Equally important, the time when a van was not available for service correspondingly increased, as did the demand for spare replacement vehicles to keep a service engineer on the road while his own vehicle was under repair.

Closely related to any decision on type and make of vehicle selected and the ultimate replacement policy adopted was the topical and thorny problem of maintenance. Many operators with relatively small fleets of 10 vehicles or so were having to make urgent reappraisals of their maintenance arrangements to meet the more stringent statutory requirements and inspections now being made. So how about the operator with 1,000 vehicles dispersed throughout the country? Strangely enough, apart from the reasons for adopting such a policy, there was comparatively little to report on the maintenance done by BDA on their vans. The reason was simple. They did not do any—themselves. Where one would not have been surprised to find a sizeable transport maintenance empire with vans being brought to centrallyplaced workshops for major repairs, there was in fact no such organization. The whole of the maintenance on the 1,000 BOA vans throughout their 3+ years of life is undertaken by Ford dealers in the area concerned or, in a minority of cases where such a dealer is not within reasonable distance, by the local garage.

On this vital subject of maintenance Mr. Harrow insisted that the key factor was the driver. In their case the fact that their drivers were service engineers of domestic appliances could be of psychological advantage to BDA. Their drivers had a professional interest in maintenance including due regard as to the use of their vehicles, although Mr. Harrow emphasized that they were not expected to do vehicle maintenance themselves.

Key man

It was essential that vehicles should be maintained in a roadworthy condition both as a public duty and an economic necessity. But in Mr. Harrow's view, week in week out, only the driver was in a position to report on the condition of his vehicle. To this end their service engineers, when returning their weekly log sheets, had to certify in a specially prepared section on that sheet that the brakes, lighting, steering, tyres and horn were in good order. Alternatively if any of these were not in good order he had to state the date and person to whom he had reported the defect.

On the subject of responsibility for keeping vehicles in a roadworthy condition, Mr. Harrow said that while they supported every move towards greater road safety he had reservations as to the ultimate value of spot inspection schemes. In their case, if they were to employ an inspector to undertake spot checks on the road he would be unlikely to be able to locate and then inspect, at an optimistic assessment, more than four vans a day, or 1,000 a year.

Therefore, on average, each of their vans would not be inspected more than once a year. This would present a situation where it would be largely fortuitous if any inspection revealed in time a defect which could be remedied. Even if they were to contemplate employing say 10 or even 20 inspectors at more than £1,000 a year each, the actual number of inspections of each van would be comparatively spasmodic and long-term.

Authority for action

No comprehensive scheme of inspection on these lines, despite its inevitable high cost, could be a substitute for continuing inspection by the driver himself provided he was both encouraged to do this and was given the authority to have the necessary repairs done at the selected local dealer when defects were found.

I put to Mr. Harrow the view expressed by many transport operators that the reason they preferred to do their own maintenance was that they thereby ensured that they knew what work was being undertaken on their vehicles.

While appreciating this attitude, Mr. Harrow contended that where one had the large maintenance staff necessary to deal with 1,000 vehicles or more the problem of adequate supervision still arose. Short of the ownerdriver or small fleet operator who literally did his own maintenance there was always the possibility of inadequate supervision of maintenance whether in one's own or a public garage.

But because of the wide geographical disposition of their large fleet in units of one it was just not a proposition to undertake their own maintenance and for this reason the whole of it was undertaken by local garages on the basis of the manufacturer's recommended maintenance scheme. Where, however, it was convenient to the local garage some of this maintenance and servicing was done at weekends to give the BDA service engineer maximum availability during his working week of Monday to Friday. Inpractice this often worked to advantage because the local garage might be engaged midweek on private cars wanted for use at weekends.

Purchase of petrol provided a small but illuminating example of how BDA deliberately tried to avoid building up a transport empire. In common with many other commercial users they buy their fuel at advantageous rates through the use of bunkering cards. But these are overstamped by BDA for cash payment only.

Mr. Harrow explained the reason. If, on average, each service engineer refuelled three times a week and purchased his petrol on credit the BDA service department would have had 12,000 invoices a month to handle and a corresponding number of entries on the statements rendered to them by the petrol companies. To obviate this sizeable clerical exercise each service engineer is given a £5 float with which to make these purchases for cash for which he is subsequently reimbursed. What benefits had arisen from the merger of servicing interests under BOA? Mr. Harrow stressed that first and foremost the customer had been given a wider geographical coverage with a resultingly more efficient and prompt service. There has obviously been benefits through bulk purchase of vehicle and supplies. There had also been savings in the provision of spare vehicles.

Spare vehicles

It was essential that the non-effeCtive time of their service engineers should be reduced to a minimum. When, despite routine maintenance, an engineer's vehicle had to be taken off the road two alternatives were available to him. If, for example, he was located in Cornwall it might provide a saving both in time and expense if he were to hire a replacement vehicle in the locality for a day or so. Alternatively if it was likely to be a longer job he could make arrangements to collect or have delivered a spare vehicle from the holding point.

Because of the relationship between the distance from the holding point it followed that greater use would be made of the spare vehicles by service engineers relatively near. But despite their sizeable fleet they have found it necessary to have only approximately 20 spare vehicles or 2 per cent of the total) to ensure that their service engineers were kept on the road.

Finally, as regards vehicle specification, Mr. Harrow said that the operation of a fleet of the size of BDA did compel one to take a closer look at the cost of extras to the basic specification. Thus, to quote only one random example, the addition of a spare wheel, passenger seat and sun visor in their vans added around £25,000 to their total fleet cost.

With amounts like that involved one had to make doubly sure that the expenditure was justified in relation to the possible eventuality involved—for example, a puncture not only on the road but remote from possible assistance.

Basic savings

Therefore, despite criticism in some quarters that commercial vehicle manufacturers did not provide full equipment for their vehicles at the standard price, Mr. Harrow supported the policy of a minimum but legally adequate specification with any extras listed at specific prices. This enabled large users such as themselves to save considerable sums on what might otherwise be standard specification of only marginal advantage in their particular type of operation.