Scottish Freight moves ahead

Page 27

Page 28

Page 29

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

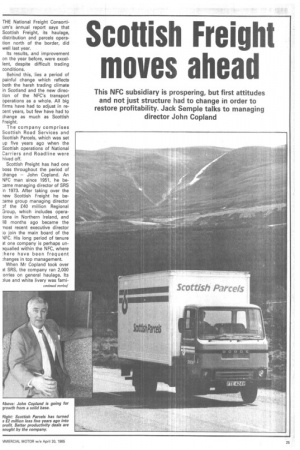

This NFC subsidiary is prospering, but first attitudes and not just structure had to change in order to restore profitability. Jack Semple talks to managing director John Copland

THE National Freight Consortium's annual report says that Scottish Freight, its haulage, distribution and parcels operation north of the border, did well last year.

Its results, and improvement on the year before, were excellent, despite difficult trading conditions.

Behind this, lies a period of painful change which reflects both the harsh trading climate in Scotland and the new direction of the NFC's transport operations as a whole. All big firms have had to adjust in recent years, but few have had to change as much as Scottish Freight.

The company comprises Scottish Road Services and Scottish Parcels, which was set up five years ago when the Scottish operations of National Carriers and Roadline were hived off.

Scottish Freight has had one Loss throughout the period of change — John Copland. An NFC man since 1951, he became managing director of SRS In 1973. After taking over the new Scottish Freight he became group managing director of the £40 million Regional Group, which includes operaions in Northern Ireland, and 18 months ago became the nnost recent executive director :0 join the main board of the NFC. His long period of tenure 3t one company is perhaps unaqualled within the NFC, where :here have been frequent :hanges in top management.

When Mr Copland took over SRS, the company ran 2,000 orries on general haulage. Its olue and white livery was fami liar not only throughout Scotland, but south of the border also.

Now. there are just 120. Although this figure is unlikely to fall any further, the chances are it will not increase much, either. In the 1970s, 30 per cent of general haulage revenue came from the whisky industry, but SRS lost out both to a decline in the industry and falling share of the available traffic. Heavy industry also has declined, particularly in the West of Scotland, causing pressure on hauliers' rates, which still show no sign of improving.

Much of the traffic is being taken by owner-drivers, who have a low capital hurdle to get into the industry, and do not need proper depot premises. In addition, says Mr Copland, "the little man can sail that bit closer to the wind."

And they do not know their costs. Many go by what big operators have quoted, assuming it must be a good rate and deduct 10 per cent rather than work out their own costs.

"You see the whole spectrum of owner-drivers, from those with old bangers with no name to others whose vehicles would be a credit to any organisation."

The market, he says, is so cut-throat that even owner-drivers who appeared to have some good ideas go under.

SRS hires trucks to ownerdrivers who compete against it. "If we didn't, someone else would."

The one strong haulage depot left in SRS is in Dumfries. The mid-way position between England and central Scotland is operationally ideal.

The end of the decline in SRS' general haulage came only last month, with the closure of the Alloa depot. It was a sad day for Mr Copland, who was general manager at Road Services Forth when the depot was opened in the late Sixties. It was highly profitable then, but was based entirely on general haulage. Some major cus tomers, including brewers, have since moved into own-account work.

"As we have pulled out of general haulage, profits have improved," says Mr Copland. And he adds that SRS remained profitable throughout each of the past 10 years. "SRS has never, ever, made a loss."

Mr Copland refuted any suggestion that SRS suffered from a bad reputation. "The only problem was at one of the Glasgow depots. We do not have any general haulage vehicles in Glasgow any more."

As SRS has got out of general haulage, it has developed into distribution, contract hire and engineering services. It has 280 trucks on contract hire, 30 on common user distribution, and has 30 trucks available for rental. The vehicles are on average two years' old.

The groundwork for expansion in these areas has been to recruit specialist managers and give them specific areas to develop. John Sanderson, in charge of developing distribution contracts, was distribution director with a subsidiary of Grand Metropolitan. The status of engineering director was lan Blundell's department was raised. His department is now a profit centre in its own right, and charges Scottish Freight operating companies. Last year it brought in £3 million from completely third-party contracts. Similarly, computer specialists have been recruited to develop systems for Scottish Freight.

Conversion of own-account fleets is perhaps SRS's biggest market opportunity at present, whether it is a complete dedicated system or contract hire. It already has a number of warehousing and distribution contracts with firms like Esso and Nestles, and is seeking more contracts in specific market sectors.

"The most challenging thing is to improve reliability and service standards. We have to convince them that our people can be just as committed as their own.

"If your business is good, you can by and large demand a bit more on the price.

"If not, you can't give it away." Following NFC's purchase of SPD from Unilever at the end of last year, there is obvious uncertainty about the future of SPD's four Scottish depots — in Renfrew, Airdrie, Inverness and Aberdeen. Mr Copland says the future of these depots is under discussion at present between himself and Ron Irons, the former BRS Western managing director now running SPD.

While the re-alignment of SRS from almost entirely general haulage to contract hire, distribution and engineering has been relatively painless in terms of profitability, the parcels operation has been very different.

When NC and Roadline parcels were brought into Scottish Freight five years ago, they were losing £1 million a year each. Shortly after the move NC parcels suffered a severe blow when its biggest source of revenue, the British Rail express parcels service, was ended. In addition, the companies had a poor image.

The outlook was bleak, to say the least. Scottish Parcels embarked on a programme not only of moving the two separate organisations into shared depots, as has happened to some extent in England, but completely merging the businesses. It now has a totally integrated network of just six depots.

"Everybody said that it would never be done, that it was impossible." The problem was the difference in union representation — NC was National Union of Railwaymen, Roadline workers were in Transport and General Workers' Union.

In fact the merger has been "most successful," says Mr Copland. Substantial losses in 1981 were reduced over the following two years, and Scottish Parcels moved into profit in 1984. Mr Copland attributes the success partly due to the the quite evident seriousness of both companies' losses, and the fact that it could survive occasional hiccups during the change because much of the traffic came from national contracts in England.

Mr Copland is given considerable personal credit by union negotiators, however. "He is one of the few fair men you meet in the road haulage industry," one said.

Scottish Freight now enjoys stable industrial relations. It has a perhaps unique position of having the NUR, TGWU, Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers and Transport Salaried Staffs' Association sitting down at the one table to discuss pay.

Attitudes and not just structure had to change if profitability was to be restored. The prevailing attitude was: "We'll try to make the delivery today," but standards offered by other carriers now mean that service levels have to be met — even if it means occasionally sending a truck on a 60-mile round trip with one parcel, for example.

"You hear of times when the boss of a small firm puts a parcel in the boot of his car to make a delivery which has been missed by the truck," I commented.

"I've done that before," says Mr Copland.

Scottish Parcels has substantially improved its image, he believes. Most employees recognise their responsibilities — although a few do not. The company is developing business within Scotland, including a same-day service between Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee and Aberdeen.

The NFC's parcels operations in England and Wales pose the one threat to the new stability of Scottish Parcels. The Parcels Group has been given this year to make inroads into the £8.2 million loss reported last year, and severe contraction cannot be ruled out if the losses cannot be reduced, I suggested.

The Scottish operation still relies on the English companies for 40 per cent of its revenue, and some of this could be lost. But Scottish Parcels would survive, Mr Copland says.

Throughout Scottish Freight, there is a campaign to improve service levels and the image of the operations. "We are going for excellence," Mr Copland says. "There are traditionally accepted ways of doing things. 'That's good enough.' Its been

OK for 15 or 20 years, but now we're saying 'That's not good enough.'

"A lot is by personal example." Around 100 man agers were at a two-day confer ence this month aimed at driving the message home. A competitive league table is a likely innovation to encourage depots to improve service levels further. He adds: "We've still got a long way to go on productivity schemes."

At February's NFC annual general meeting, attended by 2,000 shareholders, Mr Copland proposed, without success, that there should be a board mem ber representing employees. There is already a non-executive board member for shareholders.

"At the end of the day the business is all about the people who work in it. A lot of people did not buy shares at first because of advice from their union, or personal financial cir

cumstances. A director with overriding responsibility for

employees would bridge the gap between shareholders and non-shareholders."

It is healthy that the subject can be fully discussed, he says.

Scottish employees, it should be added, were less enthusias

tic about buying shares than those elsewhere in the NFC. It appears not to have hindered the recovery to profit of Scottish Freight, I suggested.

Scottish transport has an inescapable character of its own, which marks it as dif ferent from the rest of the country. Scottish Freight's ad vertisements promote the fact that it is owned by its employees, but you have to look very hard to see the reference to its ultimate NFC ownership.

Nonetheless, Scottish Freight is a good example of how large firms are having to change to meet changes in the demands of customers.