i Makng tracks

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

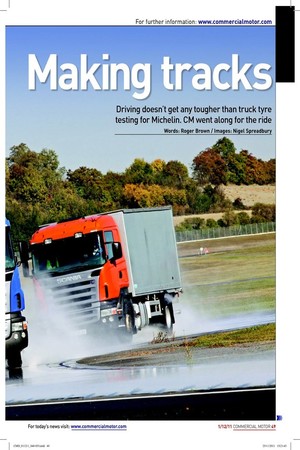

Driving doesn’t get any tougher than truck tyre testing for Michelin. CM went along for the ride

Words: Roger Brown / Images: Nigel Spreadbury

Being a truck tyre tester for a major global tyre manufacturer must rank as one of the most desirable jobs for a career HGV driver.What could be further from the misery of sitting in trafic jams on the M25 than spending your working days behind the wheel of a high performance lorry on a twisting test track set against stunning mountain scenery?

It’s a warm October day when CM visits Michelin’s vast Ladoux test track near Clermont-Ferrand, in the Auvergne region of mid France, to speak with Jacques Brange, leader of the company’s team of development drivers. Brange, a trained engineer, joined the tyre irm in 1979 and initially worked on the construction of the circuit. When building work ended, an opportunity arose to work as a tester.

If Carlsberg made jobs...

“I decided to join Michelin’s two-year training programme for tyre testers, and get my truck licence,” he says. “During the training you get to experience all types of surfaces – dry and wet ground, snow and ice. In my opinion driving trucks is more exciting than cars, I really do enjoy my job, it’s very rewarding.” The Ladoux site covers 450 hectares and includes a network of 19 tracks, with a total distance of 41km. It includes a high-speed banked section, as well as bumpy surfaces designed to test all types of urban and off-road rubber. Next to the track are a variety of ofice buildings and workshops, which house a leet of Michelin-owned trucks from all the major manufacturers: Renault, MAN, Volvo, Scania, Iveco, Mercedes-Benz and DAF.

Brange says: “The tests involve a combination of subjective and objective observations from us, which we relate back to the engineers.With subjective testing, you have to analyse and think about the results in a detached way. Objective observations are purely the driver’s feelings. The important thing is to try to memorise your indings so you can provide the engineers with the correct feedback later.” The irst demonstration is a rolling resistance trial involving two Scania R420 tractor units, one orange, the other blue.

Both vehicles pull trailers from a local manufacturer, weigh 18.5 tonnes, and carry steel girders as ballast. They have identical engines and tyre pressures, but while one is itted with Michelin’s latest Multiway 3D tyre, the other uses inferior “reference” rubber.

Jean-Franqois Belhomme, who has been a test driver for the past 10 years in a career at Michelin that spans three decades, takes us for a drive in one of the Scanias. “We do all the usual checks before a test like any driver would do before he goes to work, such as tyre pressure checks and load checks,” he says. “Our job is to test for Michelin, not the truck manufacturers, so we are looking to develop and adapt tyres for all types of vehicles.” Belhomme and Brange pull away at the same time and head off down the long straight at the same speed.They are side by side when they lick their gearboxes into neutral and let the lorries roll along the tarmac.

The Scania itted with the higher performance Multiway tyres rolls 50m further than the other one, demonstrating its superior rolling resistance.

A complex product

Belhomme says: “There are more than 200 components in a tyre, making it a complex product to analyse. Developing a new tyre is a balance of performance between improving safety, getting more mileage per tyre and increased fuel savings. It’s a dificult balancing act to increase all these elements of performance together.” On the track, the testers typically travel at speeds of up to 110km/h (70mph). Each working day they are given a speciic job to carry out: this can include testing levels of grip, noise, comfort or handling. They spend about four or ive hours maximum per session, then write reports for feedback to the Michelin technicians.

According to Belhomme, the drivers compare each other’s results and discuss whether they are experiencing the same feeling on the track. “As a tester I am constantly asking myself: is my feeling about a particular tyre the correct feeling? It helps to be able to share information with the rest of the team.” The drivers go off to put the Scanias in the garage and it new tyres to another mystery lorry, in preparation for the second demonstration. In the meantime, Robert Radulescu, one of the development bofins at Michelin, tells us how the company usually spends about seven years developing a tyre from start to inish. The early phase sees a team of experts analyse the interaction between a potential new tyre and a wheel. At this stage, teams using dynos might carry out up to 100 separate tests on a brand new tread pattern.

Radulescu says: “Our main aim is to develop safe, affordable tyres which have less impact on the environment, and tyres with better grip and higher robustness.” By this time, Brange and Belhomme have returned to the circuit.

For the next demonstration, we climb into the yellow Mercedes Actros 1848 cab with Belhomme to test Michelin’s X Energy Savergreen tyres, on one of the longer, twistier conigurations. Out on the circuit, he immediately demonstrates his driving skills by sliding the truck over the kerb and onto the grass at around 100km/h, but seemingly in complete control throughout.

“You must drive instinctively, look at the reaction of the truck and see if it has good stability on the tyres being tested,” he says. “Some of the questions you ask as a tester are: is the handling on these tyres progressive and is the responsiveness good? Is there understeer or oversteer and is the vehicle easy to correct on this rubber?”

Europe -vUS

As Belhomme and Branges prepare for the third and inal demonstration, Radulescu says that Michelin sees itself as the leading irm in the development of single coniguration tyre technology in Europe. “There’s a more mature market for this type of product in the US, whereas it is more common to see the 4x2 application in Europe,” he says.

“Trucks in Europe, which currently run 18 tyres in dual coniguration, could eventually run 10 instead, meaning less weight and a potential 7% drop in fuel consumption.” The tyre testers reappear in the orange and blue Scanias on a different section of the test track.

Belhomme was previously a tyre salesman for Michelin, visiting dealers and haulage irms around France. “It was a good thing for me that I sold Michelin tyres in the past, as it means I have a good idea of what our customers want and demand,” he says. “Testing truck tyres and carrying out trials and demonstrations like this is not always an easy job, but it’s a dream job if you love driving.”

Slippery when wet

The sprinkler systems are turned on, in readiness for a wet weather tyre demo. This time the blue Scania is shod with XDE 2 plus tyres, while the orange one is itted with the latest up-to-date Multiway 3D wet weather rubber.

Neither of the drivers has ever had an accident, which is hard to comprehend considering conditions such as these. On several occasions it seems Brange is about to lose control and the Scania will aquaplane and spin onto the grass, but each time he manages to keep it on the island.

“These are very slippery conditions but we are experienced in the wet as well as the dry,” he says. “When you are training to be a test driver you learn how to reach the limits of the trucks in dry conditions. Once you have mastered this, you then go out on a wet track and learn how to do this in rainy conditions.” Brange says it’s important that a test driver can understand, feel and explain the handling of a truck in different types of weather and on a mixture of surfaces. “Once you’re familiar with the limits of different vehicles in different conditions, you can deal with and correct oversteering and understeering behaviours,” he says.

Fancy a change of career and reckon you could live with the trials and tribulations of being a Michelin test driver? Well, it’s bad news, unfortunately – vacancies are rare and, when they do come up, are immediately illed from within the organisation.

One downside of the job is the problem of photographers lurking in nearby trees and bushes, looking for the top secret spy shot of a test vehicle that can be sold to road transport magazines around Europe.

“Security here is very good, but it’s part of the job. One thing you can say is at least people are interested in what we are doing,” says Brange. ■