Superheated Steam : Article No. III.

Page 29

Page 30

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By David J. Smith. Continued from page 108.

1.le previous instalment of this series, the use of superheated steam with existing plants was considered, and it may now be as well to discuss the manner in which the full advantages of superheat for mechanical transport can be secured. It is again necessary to refer to the steam motorcar, in which superheated steam worked such a revolution, for the development of the two classes of vehicle is analogous. The earlier steam cars were fitted with practically the same machinery, on a smaller scale, as the lorry of to-day. They had boilers for which almost the whole attention of the driver was required to keep the water level and the pressure right. They consumed enormous quantities of fuel and water, and it was not safe to leave 'them standing under steam unattended. In fact, so much trouble arose in running them that they would have been entirely displaced, in a very short time, by the internal combustion engine, had the highly-successful application of superheated steam and the flash boiler not taken place. The flash boiler,

specially, made the steam car what it is to-day. Although it is not intended to condemn all water and fire tube boilers out of hand, it may be as well to show what a large amount of attention the existing types of boilers require, and how seriously the further development of the steam lorry is retarded by their retention many fresh uses are open to the road wagon which uses superheated steam.

The most that can be done to the ordinary boiler is to add a superheater and thus to get a proportion of the advantage of the flash boiler from them, but, unfortunately, nothing can be done to reduce the amount of attention they require. It has often been said, in regard to steam cars, that no boiler requiring attention from the driver should ever be placed on them, because the driver's entire attention was needed for the road. Now, the ordinary fire or water tube boiler requires constant looking after. It has a water gauge, which must be watched; it contains a large volume of water, all of which must be heated before the vehicle can move ; very careful stoking is required, or there is either too little or too much steam generated ; there are very -many joints exposed to the fire ; it has large surfaces, which keep the working pressures low, and thus limit the range of the boiler; it is expensive to make and to keep up; the feed water must be free from oil, thus precluding condensation, and, consequently, the power of using the water over again; by a slight carelessness it is possible quickly to damage the boiler seriously, and even to cause an explosion ; the same approximate pressure is required, whether the lorry is loaded or light, whether running on the level or uphill, and this exposes all the parts to their maximum load continuously ; any leakage in the tube ends, or joints, cannot be seen to or repaired without taking everything apart, and then by skilled men; and it requires periodical cleaning, for the removal of fur or deposit, and a large proportitm of the heatiqg surface is ribneffective, which necessitates the use of a very cheap and dirty fuel, as oil fuel for these boilers is prohibitive on account of the amount of heat wasted.

The flash boiler, not only has none of these disadvantages, but pos sesses the following valuable advantages : It is quite impossible to burst it, or to have any serious trouble with it from either excessive steam pressure or shortage of water; it can be safely worked at a pressure quite im: sible in ordinary boilers; it produces highly superheated steam at the one operation; for light work it can be worked at a low pressure, say, xoolb., on the square inch, yet the pressure can be, if desired, almost instantly increased to soolb. or 600lb. on the square inch, or even higher ; it has no water gauge; it has no safety valve, a relief valve, on the water supply, alone being fitted; it requires no attention ; it has no joints exposed to the action of the fire gases ; all joints can be inspected and tightened, if desired, under steam; it will evaporate more water per pound of fuel than any other boiler ; it is cheap to make and to repair, the repairs being quite within the capacity of any unskilled man ; it does not need insuring; spare coils can be carried, and put in on the road, if recluired, in a few hours; oil in the feed water does not affect it at all, so that steam can be condensed and used over and over again ; no incrustation takes place; when standing, there is no pressure in the boilers ; and oil fuel can be used, with all its inherent advantages, at the same cost as coal or coke, if desired. Even these few advantages should make the flash boiler almost universal for lorry work, just as it is in the steam-car field. The failure of one or two makers of steam lorries, in which these boilers were adopted, would seem to have frightened all others off them, and it has been left for the steam-car makers to invade the heavy field with vehicles fitted with modern methods of steam generation.

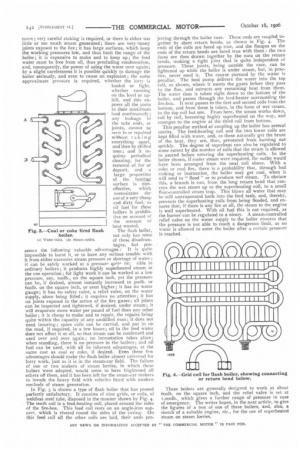

In Fig. 3 is shown a type of flash boiler that has proved perfectly satisfactory. It consists of nine grids, or coils, of weldless steel tube, disposed in the manner shown by Fig. 4. The tenth coil is a feed-heating coil, placed around the sides of the fire-box. This feed coil rests on an angle-iron support, which is riveted round the sides of the casing. On this feed coil all the other coils are laid, their ends pro

jecting through the boiler case. These ends are coupled together by short return bends, as shown in Fig. 4. The ends of the coils are faced up true, and the flanges on the ends of the return bends are faced true with them : the two faces are then drawn together by the nuts on the return bends, making a tight joint that is quite independent of pressure. These joints, being outside the case, can be tightened up while the boiler is under steam, but, in practice, never need it. The course pursued by the water is peculiar. The feed pump delivers the water into the top coil, as shown, where it meets the gases before they pass to the flue, and extracts any remaining heat from them. The water then is taken right down to the bottom of the boiler, and passes through the feed-heater surrounding the fire-box. It next passes to the first and second coils from the bottom, and from these is taken, in the form of wet steam, to the top coil but one. From here, the steam works down, coil by coil, becoming highly superheated on the way, and emerges to the engine at the third coil from bottom. This peculiar method of coupling up the boiler has several merits, The feed-heating coil and the two lower coils are kept filled with water, and, as these naturally get the brunt of the heat, they are, thus, prevented from burning out quickly. The degree of superheat can also be regulated to some extent by the number of coils that the steam is allowed to ascend before entering the superheating coils. In the boiler shown, if cooler steam were required, the outlet would have been arranged from the next coil above. With a coke or coal fire, there is a probability that, through bad stoking or inattention, the boiler may get cool, when it will tend to " flood " or to produce wet steam. To obviate this, a branch is run, from the long return bend that conveys the wet steam up to the superheating coil, to a small float-controlled steam trap. This blows all water that may be 'still unevaporated back into the feed tank, and, thereby, prevents the superheating coils from being flooded, and ensures that, if there is any fire at all, the steam to the engine is well superheated. With oil fuel this is not required, as the burner can be regulated to a nicety. A steam-controlled relief valve on the water supply to the boiler ensures that the pressure is not able to reach a dangerous limit, as no water is allowed to enter the boiler after a certain pressure is reached.

These boilers are generally designed to work at about 600lb. on the square inch, and the relief valve is set at 1,000lle., which gives a further range of pressure in case of emergency. The writer hopes, in the next article, to give the figures of a test of one of these boilers, and, also, a sketch of a suitable engine, etc., for the use of superheated steam on steam lorries.