The champion goes to Holland

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The 1974 Lorry Driver of the Year spent four days in Europl recently as a guest of Michelin. He asked the questions, 'ail Sherriff writes the story

LLOYD RICHARDS, the 1974 Commercial Motor Lorry Driver of the Year, has just completed 250,000 miles of accident-free driving.

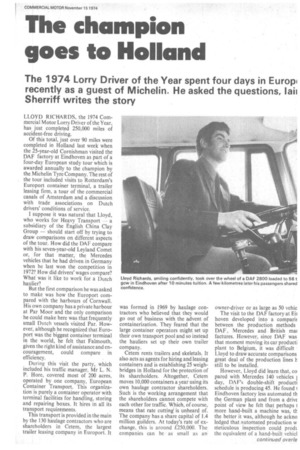

Of this total, just over 90 miles were completed in Holland last week when the 25-year-old Cornishman visited the DAF factory at Eindhoven as part of a four-day European study tour which is awarded annually to the champion by the Michelin Tyre Company. The rest of the tour included visits to Rotterdam's Europort container terminal, a trailer leasing firm, a tour of the commercial canals of Amsterdam and a discussion with trade associations on Dutch drivers' conditions of service.

I suppose it was natural that Lloyd, who works for Heavy Transport a subsidiary of the English China Clay Group — should start off by trying to draw comparisons on different aspects of the tour. How did the DAF compare with his seven-year-old Leyland Comet or, for that matter, the Mercedes vehicles that he had driven in Germany when he last won the competition in 1972?, How did drivers' wages compare? What was it like to work for a Dutch haulier?

But the first comparison he was asked to make was how the Europort compared with the harbours of Cornwall. His own company has a private harbour at Par Moor and the only comparison he could make here was that frequently small Dutch vessels visited Par. However, although he recognized that Europort was the biggest container terminal in the world, he felt that Falmouth, given the right kind of assistance and encouragement, could compare in efficiency.

During this visit the party, which included his traffic manager, Mr L. N. P. Hore, covered most of 200 acres, operated by one company, European Container Transport. This organization is purely a container operator with terminal facilities for handling, storing and repairing boxes. It hires in all its transport requirements.

This transport is provided in the main by the 130 haulage contractors who are shareholders in Cetem, the largest trailer leasing company in Europort. It was formed in 1969 by haulage contractors who believed that they would go out of business with the advent of containerization. They feared that the large container operators might set up their own transport pool and so instead the hauliers set up their own trailer company.

Cetem rents trailers and skeletals. It also acts as agents for hiring and leasing containers and is establishing 25 weighbridges in Holland for the protection of its shareholders. Altogether, Cetem moves 10,000 containers a year using its own haulage contractor shareholders. Such is the working arrangement that the shareholders cannot compete with each other for traffic. Which, of course, means that rate cutting is unheard of. The company has a share capital of 1.4 million guilders. At today's rate of exchange, this is around £250,000. Thecompanies can be as small as an owner-driver or as large as 50 vehic The visit to the DAF factory at Eh hoven developed into a comparis between the production methods DAF, Mercedes and . British mai factures. However, since DAF was that moment moving its car producti plant to Belgium, it was difficult Lloyd to draw accurate comparisons great deal of the production lines Ii still to be installed.

However, Lloyd did learn that, co pared with Mercedes 140 vehicles I day, DAPs double-shift producti schedule is producing 45. He found 1 Eindhoven factory less automated th the German plant and from a drive point of view he felt that perhaps more hand-built a machine was, th the better it was, although he ackno ledged that automated production w Meticulous inspection could prodt the equivalent of a hand-built vehicl

continued overle This year DAF's out put will he on topside of 14,000 vehicles. The 30 target is 18,000 vehicles.

Following the visit and two inuctional films in the factory, the party off on a demonstration drive using a ILE 2800 fitted with twin-bunk sleeper ), radio and cartridge player and susision seats. This was described by the monstration driver as a standard )del, and Lloyd's first reaction was it while that might be so for the erator buying only a few vehicles, ge fleet operators in the UK seldom if considered the comfort of suspenn seats or the company of in-cab tertainment as being part of their ndard equipment.

The other vehicle, a DA F. 2200 noneper cab, described as a super nfort cab had more of the iracteristics that the British driver I become used to. But here again the tpension seats were perhaps more :urious than those generally specified British operators. Lloyd Richards ressed a sentiment common to many itish drivers that operators should y more attention to the drivers' inion of a vehicle and rather less to extra few per cent discount that they ght get by reducing the cab comfort. The first part of the drive took the .m of a talk-through demonstration a Dutch driver. This was over within i minutes and the champion took the Led. For the first few kilometres he s a little confused with the range inge Fuller gearbox, but since his ite was along a narrow one-way road [ere he could not be overtaken, the a that he let the steering wander while ling out his gears caused conrnation only to the instructor and 7self and we promised to say nothing out it!

The 2800 is surely among the quietest the road. Instructions to Lloyd were ssed in normal conversational tones d were perfectly audible. The engine s so quiet that during this first driving !:11 he found difficulty in judging gearInge points by ear. When he changed the lighter 2200, Lloyd's first mment was: "I'm happier with he. I .1 hear the engine." This time he was ng a straight six-speed ZF box and art from the fact that the roads were t, we might have been driving with n in his native Cornwall.

wo criticisms

The 2200 is fitted with a 161 kW 16 bhp) engine, which Lloyd criti!ed on two counts. Even at the uivalent of 80km/ h (50 mph) it ,peared to rev high. This was later nfirmed by the DAF driver who said at at this speed it was running at 1800 rpm. His second criticism was that it appeared to be underpowered. The vehicle was empty and Lloyd said, that despite its old age his Leyland Comet when empty surged away from a standing start in second gear.

It became obvious as this part of the drive progressed that the champion had mastered the unfamiliar road conditions. He overtook other vehicles with ease and observed the basic principles of our own highway code when passing through towns and villages or encountering road works.

The confidence gained in the 2200 served Lloyd well when he returned to the 2800 for the final part of the journey. The machine was laden to 56 tons gross with rubble. It held the road well and pulled its weight with comfort. At 5 bhp per ton the Dutch power to weight ratio is 1 bhp less than in Britain and 3 less than in Germany, but again comparisons between his normal working situation and his drives in Germany and Holland were impossible because of the different ages of his own vehicle and the 2800 and because the Dutch route did not produce the gradients that he had experienced in Germany with the new Mercedes vehicles.

Drivers are seldom recognized by their managers as being cost-conscious individuals. Nevertheless, Lloyd had one or two cost questions to put to the DA F executives whom we met at the end of the journey. For example, he learned that road fund tax for the 56ton-gross outfit was about £2,600, but that fuel cost around 30p a gallon. Drivers' wages for local delivery work amount to about 250 guilders — which is about £40. But the Dutch transport system has created almost a two-class society for its drivers, because a longdistance man can pick up 1100 guilders a week, which is about £200. We were told that only 250 guilders of this is declared for tax, since the balance includes over night allowances, subsistence and other out-of-pocket expenses.

It was reckoned that few Dutch long distance drivers remained in the job for more than 15 years. Many voluntary retire after 10 years and start up in business for themselves, but not in road haulage. A typical run for a •Dutch driver is from Eindhoven to Trieste through France. These men leave at 4pm on a Tuesday and are back in the Eindhoven depot having completed 2,100 miles by 6pm on the Friday. For this they are paid the equivalent of £160.

Short-distance pay

The local delivery driver in Holland has the same basic wage as a longdistance driver in Britain but this is for a 45-hour week with little opportunity of earning overtime.

Lloyd Richards is a married man and naturally he wished to know something of living expenses. Accommodation costs between £10 and £16 a week to rent a two-roomed' house, so local delivery men with a £40 pre-tax wage are now finding themselves more and more encouraging their wives to take up employment. Their more affluent colleagues on the long-distance work are entering the owner-occupier sector of the community where a three-bedroom house can still be obtained for around £12,000. We were told that inflation is running at about 10 per cent. During a window shopping expedition, Lloyd Richards found that almost everything was dearer than in Britain.

In a typical drivers' cafe, the champion and his entourage sat down to a waitress service lunch of pea soup, wiener schnitzel with three veg, chocolate blancmange with custard, and coffee, which cost the equivalent of £1.50. The establishment was comfortable, with carpeting, clean tablecloths and undogged condiment sets. Later we looked at the car park and, not surprisingly, the only vehicles parked there were those of the "rich" long-distance men.

Big business

Road haulage is big business for the Dutch. who claim to be carrying 40 per cent of Europe's international road traffic. Unlike the UK where the two main trade associations are divided clearly into hire and reward or ownaccount activities, there are five associaticns for operators in Holland. It is estimated thaat the own-account association — EU0 — caters for 70 per cent of the operators, and that the other four cater for road haulage and passenger operators. The largest of these four is NOB which looks after the largest number of companies and is possibly the most influential of the trade associations. ANUTO is the association which mixes both haulage and passenger activities and has large fleet operators as its principal members. The two remaining associations draw a distinction between Protestant and Catholic operators; PCB is the Protestant association, KUO the Catholic. The own-account sector has 40,000 members, the remainder totals around 23,000. Membership of an association is compulsory.

During the trip to the commercial canals it was explained that their function was to link the port of Amsterdam with the warehousing section, which had been built in the centre of the old town. Some of the original warehouses still stand despite wartime devastation in the city centre. In the heart of this transport complex stands a building which Lloyd's guide described with a sense of humour as a former lunatic asylum which had now been converted into an income tax office. With an equally sharp sense of humour, the champion commented: "Much the same thing."

The final part of the study tour consisted of two trips on passenger vehicles. The first was a tram ride the first Lloyd had ever been on — with four carriages close-coupled, one-man operation, and a ticket issuing and franking machine carried in the rear coach. The doors of Dutch trams can be opened either from the inside or the street, but boarding passengers who require tickets must enter from the rear coach where the ticket equipment is carried. Although season tickets are available, the normal flat fare 1 guilder system is the most popular. A ticket is issued on insertion of the coin and it entitles a passenger to one return journey. It has to be inserted in a franking machine which date and time stamps the outward part of the ticket and detaches the bottom edge.

Intrigued

Lloyd was intrigued at the way people boarded and left the tram, all presumably in possession of either a return or a season ticket, but never at any time during the course of a five-hour riding and walking trip did he see an inspector. Fare evasion seemed possible. Later he was told that the inspectors travel in teams (and in civilian clothes) so that they enter each section of the tram at the same stop, thus preventing non-ticket holders from leaving by one door as might happen with a single inspector.

While travelling on the bus, he was delighted first of all to learn that it was a Leyland and even happier to hear from the driver that he was more than pleased with its handling and performance. But when we left the vehicle, Lloyd was not particularly complimentary about the driver's ability!

Having heard that the DAV!, had been built almost to a driver's specification, his comment was th drivers were seldom, if ever, consulted the UK. Lloyd criticized manufacture for failing to provide drivers' han books with nevci vehicles and genera treating drivers with much le importance than they merited in th very little information was commur cated to them by either manufacturer management. An example of how t Dutch tackle this question came when he suggested that the DAr 281 steering wheel was much too big f comfort. It was pointed out that t wheel size had been chosen after a gre deal of research with both engineers at drivers, and it had been found that ti 28 cm (11.2 in) radius brought the art into the most relaxed position for Ion distance drivers.

During his driving trip, Llo] commented on this aspect and he four that after many miles his hands were st on the steering wheel whereas in son trucks he would have been inclined • have rested his elbow on the window that stage. The same applied to the DA 2800 gear lever and dash panel contr which he found required the minimu of effort to operate. He also approved , the uninterrupted view of the dash pan through the steering wheel and ti unobstructed vision afforded by ti wide windscreen.

Clydesdale or Chieftain

Lloyd's seven-year-old Leylar Comet is due for replacement short and after two Michelin trips to Europ could he be criticized if he craved for lightweight Continental for a changl Perhaps not, but then he is not lookir for such a vehicle. "I wouldn't mind Clydesdale or a Chieftain," he said, ad( ing that he was a short-distance ma who didn't get too far away from horn, During the trip one of the Dutc hosts, having had the competitio explained to him, asked what the chan pion could gain in addition to the prize For the first time I learned that aftt his 1972 triumph, Lloyd Richarc received seven offers of posts as a instructor. All of them away from h native Cornwall, and perhaps that wz why they were refused at that time.

The situation could be different thi year if similar offers come forward, bu what would he really like to do? I pilot th question to him. "I think whe operators buy a new range of vehicles, member of the driving staff should b sent to the manufacturers to learn every thing there is to know about the vehicl and then come back and pass th information on to the rest of the drivin staff. That's the kind of job I think could do," he said. So if Heavy Trans port is wondering how to best use Lloy4 Richards' talents, that might serve as a useful hint.