Atlas Ambulance mooth and Nimble

Page 70

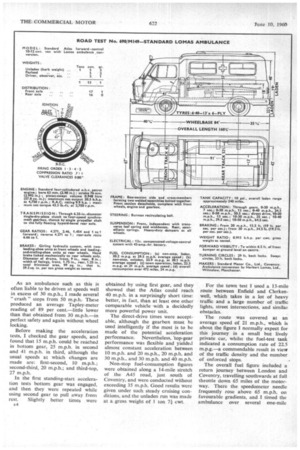

Page 71

Page 72

Page 73

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

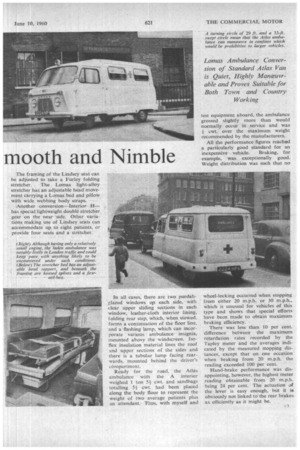

By John F. Moon, A.M.I.R.T.E. BECAUSE of its vice-free suspension, the Standard Atlas 10-12cwt. van makes a good basis for an ambulance conversion. Another valuable attribute for this type of operation is the high degree of manoeuvrability afforded by a 33-ft. swept turning circle.

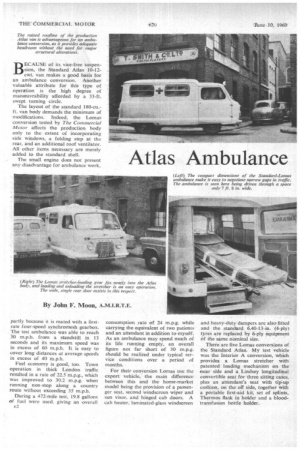

The layout of the standard 180-cu.ft. van body demands the minimum of modifications. Indeed, the Lomas conversion tested by The Commercial Motor affects the production body only to the extent of incorporating side windows, a folding step at the rear, and an additional roof ventilator. All other items necessary are merely added to the standard shell.

The small engine does not present any disadvantage for ambulance work, partly because it is mated with a firstrate four-speed synchromesh gearbox. The test ambulance was able to reach 30 m.p.h. from a standstill in 13 seconds and its maximum speed was in excess of 60 m.p.h. It is easy to cover long distances at average speeds in excess of 40 m.p.h.

Fuel economy is good, too. Town operation in thick London traffic resulted in a rate of 22.5 m.p.g., which was improved to 30.2 m.p.g. when running non-stop along a country route without exceeding 35 m.p.h.

During a 472-mile test, 19.8 gallons of fuel were used, giving an -overall E2 consumption rate of 24 m.p.g. while carrying the equivalent of two patients and an attendant in addition to myself. As an ambulance may spend much of its life running empty, an overall figure not far short of 30 rn.p.g. should be realized under typical service conditions over a period of months.

For their conversion Lomas use the export vehicle, the main difference between this and the home-market model being the provision of a passenger seat, second windscreen wiper and sun visor, and hinged cab doors. A cab heater, laminated-glass windscreen and heavy-duty dampers are also fitted and the standard 6.40-13-in. (4-ply) tyres are replaced by 6-ply equipment of the same nominal size.

There are five Lomas conversions of the Standard Atlas. My test vehicle was the Interior A conversion, which provides a Lomas stretcher with patented loading mechanism on the cear side and a Lindsey longitudinal convertible seat for three sitting cases, plus an attendant's seat with tip-up cushion, on the off, side, together with a portable first-aid kit, set of splints, Thermos flask in holder and a bloodtransfusion bottle holder. The framing of the Lindsey seat can be adjusted to take a Purley folding stretcher. The Lomas light-alloy stretcher has an adjustable head movement carrying a Lomas bed and pillow with wide webbing body straps.

Another conversion—Interior H— has special lightweight double stietcher gear on the near -side. Other variations, making use of Lindsey seats can accommodate up to eight patients, or provide four seats and a stretcher.

In all cases, there are two purdahglazed windows op each side, with clear upper sliding sections in each window, leather-cloth interior lining, folding rear step, which, when stowed, forms a continuation of the floor line, and a flashing lamp, which can incorporate various ambulance insignia, mounted above the windscreen. Isoflex insulation material lines the roof and upper sections of the sides and there is a tubular lamp facing rearwards, mounted behind the driver's compartment.

Ready for the road, the Atlas ambulance with the A interior weighed 1 ton 5-1 cwt. and sandbags totalling SI cwt. had been placed along the body floor to represent the weight of two average patients plus an attendant. Thus, with myself and

test equipment aboard, the ambulance grossed slightly more than would normally occur in service and was .3f cwt. over the maximum weight recommended by the manufacturers.

All the performance figures reached a particularly good standard for an inexpensive vehicle. Braking, for example, was exceptionally good. Weight distribution was such that no wheel-locking occurred when stopping from either 20 m.p.h. or 30 m.p.h., which is unusual for vehicles of this type and shows that special efforts have been made to obtain maximum braking efficiency.

There was less than 10 per cent. difference between the maximum retardation rates recorded by the Tapley meter and the averages indicated by the measured stopping distances, except that on one occasion when braking from 20 m.p.h. the reading exceeded 100 per cent.

Hand-brake performance was disappointing, however, the highest meter reading obtainable from 20 m.p.h. being 24 per cent. The actuation of the lever is easy enough, but it is obviously not linked to the rear brakes as efficiently as it might be. As an ambulance such as this is often liable to be driven at speeds well in excess of 30 m.p.h., I made several " crash " stops from 50 m.p.h. These produced an average Tapley-meter reading of 89 per cent.—little lower than that obtained from 30 m.p.h.—in perfect safety and again without wheel locking.

Before making the acceleration tests, I checked the gear speeds, and found that 15 m.p.h. could be reached in bottom gear, 25 m.p.h. in second and 41 m.p.h. in third, although the usual speeds at which changes are made are: first-second, 10 m.p.h.; second-third, 20 m.p.h.; and third-top, 27 m.p.h.

In the first standing-start acceleration tests bottom gear was engaged, and then they were repeated while using second gear to pull away from rest. Slightly better times were E4 obtained by using first gear, and they showed that the Atlas could reach 40 m.p.h. in a surprisingly short time: better, in fact, than at least one other comparable vehicle with a decidedly more powerful power unit.

The direct-drive times were acceptable, although the gearbox must he used intelligently if the most is to be made of the potential acceleration performance. Nevertheless, lop-gear performance was flexible and yielded almost constant acceleration between 10 m.p.h. and 20 m.p.h., 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h.. and 30 m.p.h. and 40 m.p.h.

Non-stop fuel-consumption figures were obtained along a 14-mile stretch of the A45 road, just south of Coventry, and were conducted without exceeding 35 m.p.h. Good results were given under such steady cruising conditions, and the unladen run was made at a gross weight of 1 ton 7.71cwt.

For the town test I used a 13-mile route between Enfield and Clerkenwell, which takes in a lot of heavy traffic and a large number of traffic lights, street intersections, and similar obstacles.

The route was covered at an average speed of 21 m.p.h., which is about the figure I normally expect for this journey in a small but lively private car, whilst the fuel-test tank indicated a consumption rate of 22.5 m.p.g.—a commendable result in view of the traffic density and the number

of enforced stops. • The overall fuel figure included a return journey between London and Coventry, travelling southwards at full throttle down 65 miles of the motorway. There the speedometer needle frequently rose above 65 m.p.h. on favourable gradients, and I timed the ambulance over several one-mile sections at speeds between 57 m.p.h. and 60 m.p.h. Rarely did the speed fall below 50 m.p.h. on the motorway.

Bison Hill, to the west of Dunstable, was the scene of further tests. It is mile long and has an average gradient of 1 in 10+, the steepest section measuring 1 in 61. The ascent was carried out in an ambient temperature of 55° F. and took only 2 minutes 27 seconds, which is one of the fastest times ever recorded. The minimum speed was 14 m.p.h. and the lowest gear used was second. This was engaged for 52 seconds.

Water Bubbled

Before the climb the engine-coolant temperature had been 164° F. and the test caused it to rise by 26° F., so that some of the water bubbled out of the filler neck when I removed the radiator cap. This would suggest that the cooling system is a little near the limit, although it is pressurized to raise boiling point above 212° F.

It had started to rain by the time I was ready to make a fade test down the hill. This run lasted 2 minutes 20 seconds and was made by coasting in neutral while using the foot brake to restrict the speed to 20 m.p.h. Towards the bottom of the hill, where the gradient is not so severe, I engaged top gear and applied full throttle to give the brakes something to work against.

At the end of the descent I made a full-pressure foot-brake stop and, although all the wheels locked because of the wet road, a Tapley-meter reading of 70 per cent. was obtained, which indicates a negligible degree of fade. There was little increase in the pedal pressure and no smoke was issuing from the drums.

Ruthless Slipping

Having returned to the 1-in-61 section, I stopped the ambulance there, but the hand brake would only just hold it. I was unable to restart in second gear, even though I slipped the clutch somewhat ruthlessly, but the vehicle moved away smoothly in bottom gear, using only a third of the available throttle travel.

Handling was extremely good at all times and the absence of roll on sharp corners was marked. Even though the tyres can be made to squeal without much provocation, and in extreme instances the inner rear wheel can be lifted clear of the ground, the front suspension keeps the body upright.

At times a sudden side wind affected the steering slightly, even when cruising at about 30 m.p.h. on a normal road, but generally the steering characteristics were good and the ambu

lance was light to handle at all times. The narrow 'front track permits an exceptional steering lock, which gives a turning circle of 29 ft.

Except at peak revolutions, the engine was quiet. There was a certain amount of gearbox whine in the indirect gears, but the body was remarkably free from rattles.

The engine was found to pink slightly when running on regular petrol, as used for the majority of tests, but an equal mixture of premium and regular fuels removed this tendency. On level ground it idled so smoothly and silently that it gave the impression of having stopped. Starting from cold after standing outside overnight was a little erratic, and the engine tended to run on when it was switched off after it had been driven hard.

Smooth Suspension Travel was comfortable, both in the driving compartment and in the body, over indifferent road surfaces, and the smoothness of the suspension over cobbles was noteworthy. The driving seat is agreeable, the short squab fitting neatly into the small of the back in the manner of a typist's chair. Both the driving and the passenger seats have a three-position fore-andaft adjustment range of 2} in.

The synchromesh mechanism permits fast gear changes and• it was almost impossible to crash the gears. Although a direct-operating gear lever, such as that fitted to the Atlas. is to be preferred to a steering-column control, it is some way back from the driving position and I found it convenient to make changes between third and top gears by using the crook of my left elbow. The clutch action was smooth and light.

Wide cab doors make for easy entry and exit, and the set-back engine compartment facilitates access to the driving seat from the kerb. Forward vision is good, but the size and loca tion of the exterior mirrors are poor, although the Lomas conversion includes a large interior mirror which gives a good range of vision through the side windows and through the rear window.

I sought professional opinion from my local ambulance station as to the quality and layout of the specialized equipment in the body and it met with approval. The Lomas stretcher loading gear is well known, but a recent innovation is the control at the rear by means of which the locking mechanism can be operated from the rear doorway. Consequently, it is unnecessary for an attendant to go to the front of the body when loading and unloading.

Although not criticized by the experts, I thought that some form of stop would be an advantage to prevent the rear door being closed with the folding step down-. An additional body heater might prove necessary in particularly cold climates, although in temperate zones the effective cab heater affords a reasonable degree of general body warmth.

Good Engine Access I did -not carry out maintenance tasks, because these were performed when the Atlas van was tested (March 6, 1959). General maintenance should not present. difficulties, access to the engine being well above average for this type of vehicle.

A unique feature of the Atlas design is the detachable forward chassis section, which can be unbolted to allow the engine, gearbox and steering to be removed on the front wheels, making an engine change an eight-man-hour job.

The 'Standard-Lomas ambulance is a particularly well-finished product, both inside and out, and it should prove acceptable to many health authorities requiring auxiliary ambulances of this size. As tested, with the A interior, it sells for £870.