.1 1 0STING• PRINCIPLES TO matter how limited the transport activities of

Page 84

Page 85

Page 86

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

a haulier, ancillary user or bus operator may be, a knowledge of costing ilways needed and, moreover, the ability to apply it to advantage successful long-term activities. On the other hand, several opera

s seem to get by with the minimum of costing records or indeed ne at all—if licensing court cases are true criteria._Unfortunately, tally is kept of the number who fail to stay,the course in transport lout becoming involved in the publicit'Y surrounding actual Aniptcy. Alternatively, in the ancillary operation of C-licence licks several factors could mislead those concerned as to the true te of their supposed transport efficiency.

Stemming from failure to base operation on sound costing, bad usekeeping in transport often reveals itself successively in inNuate maintenance, inadequate vehicles and so ultimately, if t sooner, in an inadequate service. Nevertheless, examples of &ally uneconomic operation seem to survive though they may )end on differing reasons for their continued existence.

Taking two extremes, at one end of the scale the ratio between total cost of a commodity and the cost of its distribution may so great as to devalue the apparent importance of distribution hin that particular organization. Understandably, the attitude ght then be adopted that as long as raw materials were received required and finished goods were dispatched to customers on time n its transport department was being operated efficiently. Indeed,

ROM THE POSTBAG

with so many more-important demands being made on their time, the principals of that organization might well determine that devoting some of that valuable time to obtaining marginal improvements in an already small proportion of total unit costs was a wrong evaluation of priorities. Additionally, where the basic cost of a commodity is high in relation to the cost of its distribution it often follows that there is a demand for a high standard of delivery service in that particular trade or industry, which must have a reflection on the cost of providing that service.

At the other end of the scale, for example in the movement of sand or gravel in tippers, the cost of transport constitutes a high proportion of the total cost. So the emphasis is on the vital need for transport efficiency leading to low distribution costs. Unfortunately, as licensing court cases again reveal, the reverse is not necessarily valid, namely that low distribution costs are indicative of transport efficiency.

Even when operating within the law the low rates accepted by many a small tipper operator—often an owner-driver—can be misleading as to his true efficiency. As with owner-drivers in general haulage his working day as a driver will invariably be longer than the average which applies generally in industry. But he has not finished even then. Either at evenings or weekends, or both, there will be customers to be contacted, records to be kept and other managerial functions to be performed, routine though these may be. Yet at the end of the week his earnings may be little more, if that, than employees with no responsibility in other trades or industry. In other words, by national standards such operators are virtually doing two jobs for the average rewards of one. So in effect there is an element of subsidy, albeit a personal one, in the low rates at which he operates to the chagrin of larger operators who have to absorb in their rates large, though still reasonable, administration or overhead costs.

An exercise in cheese-paring

Unfortunately costing and accountancy generally are often looked upon as largely an exercise in cheese-paring. This is unfortunate for at least two reasons. Not only does it devalue the whole exercise of costing but it obscures one of its main advantages, namely to point the way to greatest profitability. This function is obviously of advantage in all trades and industries but especially so in transport operation where crass-subsidization can more readily occur and so obscure the true profitability of the several functional sections or types of traffic which can go to make an operator's total activities. Until an adequate costing system is evolved varying degrees of profitability cannot be determined. It could well be, therefore, that much thought and effort by an operator is applied in the wrong direction though not necessarily implying, overall, that he is running at a loss.

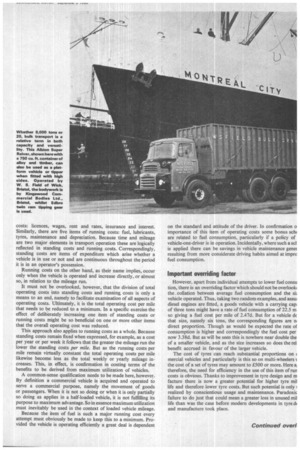

The basic division of total operating costs into the two major groups of standing costs and running costs was explained in this series recently, as were the five items which go to make up standing costs: licences, wages, rent and rates, insurance and interest. Similarly, there are five items of running costs: fuel, lubricants, tyres, maintenance and depreciation. Because time and mileage are two major elements in transport operation these are logically reflected in standing costs and running costs. Correspondingly, standing costs are items of expenditure which arise whether a vehicle is in use or not and are continuous throughout the period it is in an operator's possession.

Running costs on the other hand, as their name implies, occur only when the vehicle is operated and increase directly, or almost so, in relation to the mileage run.

It must not be overlooked, however, that the division of total operating costs into standing costs and running costs is only a means to an end, namely to facilitate examination of all aspects of operating costs. Ultimately, it is the total operating cost per mile that needs to be reduced to a minimum. In a specific exercise the effect of deliberately increasing one item of standing costs or running costs might be so beneficial on one or more other items that the overall operating cost was reduced.

This approach also applies to running costs as a whole. Because standing costs remain fixed when expressed, for example, as a cost per year or per week it follows that the greater the mileage run the lower the standing costs per mile. But as the running costs per mile remain virtually constant the total operating costs per mile likewise become. less as the total weekly or yearly mileage increases. This, in effect, is confirmation in costing terms of the benefits to be derived from maximum utilization of vehicles.

A common-sense qualification needs to be made here, however. By definition a commercial vehicle is acquired and operated to serve a commercial purpose, namely the movement of goods or passengers. When it is not so doing or when it is only partially so doing as applies in a half-loaded vehicle, it is not fulfilling its purpose to maximum advantage. So in essence maximum utilization must inevitably be used in the context of loaded vehicle mileage.

Because the item of fuel is such a major running cost every attempt must obviously be made to keep this to a minimum. Provided the vehicle is operating efficiently a great deal is dependent on the standard and attitude of the driver. In confirmation o importance of this item of operating costs some bonus scht are related to fuel consumption, particularly if a policy of vehicle-one-driver is in operation. Incidentally, where such a set is applied there can be savings in vehicle maintenance gener resulting from more considerate driving habits aimed at impro fuel consumption.

Important overriding factor

However, apart from individual attempts to lower fuel consu tion, there is an overriding factor which should not be overlooki the . collation between average fuel consumption and the si; vehicle operated. Thus, taking two random examples, and assui diesel engines are fitted, a goods vehicle with a carrying cap: of three tons might have a rate of fuel consumption of 22.5 m so giving a fuel cost per mile of 2.47d. But for a vehicle dc that size, namely six tons, the corresponding figures are ni direct proportion. Though as would be expected the rate of consumption is higher and correspondingly the fuel cost per now 3.38d. But as will be seen this is nowhere near double the of a smaller vehicle, and as the size increases so does the rel benefit accrued in favour of the larger vehicle.

The cost of tyres can reach substantial proportions on c mercial vehicles and particularly is this so on multi-wheelers N the cost of a set of tyres may amount to £500 or more. Here A therefore, the need for efficiency in the use of this item of run costs is obvious. Thanks to improvement in tyre design and m facture there is now a greater potential for higher tyre mil life and therefore lower tyre costs. But such potential is only 1 realized by conscientious usage and maintenance. Paradoxic failure to do just that could mean a greater loss in unused mil life than was the case before modern developments in tyre di and manufacture took place.

Maintenance of the vehicle as a whole is obviously a major liar in successful operation with a direct reflection on total crating costs. Moreover, recent external factors such as the wernment's determination to insist on a higher standard of fitness commercial vehicles have brought maintenance into even greater >minence. The manner in which maintenance costs can be kept a minimum is largely a technical problem but a factor which plies generally to all commercial vehicle costing needs re-emphasis the case of maintenance. It is, that although it is convenient to vise total operating costs Into 10 items so as to facilitate lividual examination they still remain interrelated. Particularly es this apply to maintenance and the fifth item of running costs, preciation.

A current additional problem in connection with maintenance is shortage of skilled maintenance staff and the high cost even ien it is available. One solution to this problem is to cut down amount of maintenance necessary by replacing vehicles more quently. Normally this would then result in servicing and light >airs being undertaken only during the time the vehicle was in operator's possession.

It would, however, increase the cost of depreciation and it would a matter of individual decision as to whether the saving on one m, namely maintenance, was likely to more than outbalance the tra cost arising from increased depreciation.

Mention has been made earlier of maximum utilization so as to itice the total operating costs per mile by spreading the fixed :al standing costs over as large a mileage as possible. In this nnection there is also another aspect of utilization to be conlered, namely obsolescence. Because of continued improvements the design and manufacture of commercial vehicles the aceumued benefits which might thereby arise over a period of, say, five ars could be so substantial as to justify replacement on the score the greater efficiency of the new model alone, even though the old >del was not worn out. A similar situation can arise in connection th the use of special-type bodies with little or no use except in anection with one flow of traffic. While the demands of aparticular ffic movement may necessitate the use of such vehicles it is perative that the effect of average weekly or yearly mileage on erating costs is recognized and acted upon in the making of the tial estimates and formulation of rates.