A three horse race This week we put three more

Page 19

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

tippers to the test eight-wheelers with single-reduction axles Following last week's test of two heavy-duty 8x4 tippers featuring hub-reduction rear axles, this test compares three more eight-wheelers, all with singlereduction axles. All have 14m3 to 15m3 steel bodies and are aimed at the muckaway sector. Their single-reduction axles put the emphasis on maximising the critical issues of payload and fuel consumption, sacrificing the off-road ground clearance advantage of hub-reduction axles. With nominal power ratings of 360hp, 400hp and 420hp, our trio of tippers covers virtually all bases in the 8x4 market, with very few buyers choosing ratings outside this range.

The brands represented — MAN, Scania and Volvo — account for three of the four top-selling tipper chassis in the UK last year. Daf's CF85, ranked third in this sector last year, is the one missing: with our test taking place just a few weeks before its new Euro-6 CF range was unveiled at last month's CV Show, Daf saw little sense in us testing the outgoing model.

Our test route and procedure is the same as that for the heavy-duty models last week. After weighing them to ascertain their unladen weights (adjusting the figures to put them on an even footing with regard to fuel load) the three tippers were loaded to close to the maximum 32-tonne gross weight limit and taken round a 60.29 mile (97.02km) test route in Oxfordshire. The route breaks down into 39.47 miles (63.52km) of undulating Aand B-roads, plus 20.82 miles (33.5km) of motorway. • [MAN TGS 32.400 The '32' prefix in the model designation indicates that this is the lighter of MAN's two 8x4 chassis; the heavy-duty one is the '35' model we covered last week. In addition to the use of single-reduction rather than hub-reduction drive-axles, the key differences are as follows: the 32's chassis is made from 7mm-thick steel instead of 8mm steel; the brakes are discs all round (the 35 has drums at the rear); and the 32's steer axles are of drop-beam rather than straight-beam design. The 10.5-litre D20 engine, rated at a nominal 400hp in the two examples we tested, is identical, but whereas it drives through an MAN Tipmatic (née ZF AS-Tronic) 12-speed automatic gearbox with overdrive top in the 35 model, this 32 has the direct-drive top version of this long-established box.

The automated gearbox is 65kg lighter than the standard trusty 16-speed ZF manual, so it should be a shoo-in for tippers. However, suspicion about the suitability of automated boxes for site work still persists in some quarters. Although it is possible to overcome that by switching to manual shift mode in an auto box, the alternative is to use the off-road programmes like the Dx mode on the MAN. This allows the engine speed to rise beyond that used on the road, thus reducing the number of shifts and interruptions to traction. We were based in a firm sand quarry, so did not have the opportunity to test this function.

We said nice things about MAN's TGS 'M' day cab and its perceived quality in last week's tipper test, and the same applies again because it is the same cab. It is the longest (1.88m) of the three cabs here, also providing the most headroom and the lowest (260mm) and least intrusive engine tunnel, so feels airy and spacious, with a reasonable amount of storage room behind the seats. There would be even more space were it not for the large intrusion in the rear bulkhead, accommodating the air cleaner on the other side of the panel.

Ground clearance is the best of the three below the roll bar, the lowest point at the MAN's back end, but the poorest beneath the bottom step, mounted on a separate tubular bracket rather than the standard TGS step moulding. The bumper is a three-section steel affair, practical but 64kg heavier than the plastic alternative.

The TGS did not need to resort to plastics in order to qualify as easily the lightest of these three tippers, weighing off at 12,360kg with a full tank of fuel (300 litres) and alloy sideguards. Few would complain about the payload potential of 19,640kg for a muckaway tipper. MAN must share the credit for this with Thompsons, which provided the Stonemaster steel body, lighter than most thanks to use of thin (3mm) high-strength steel for its single-skinned sides. The tipping gear Edbro CX14 also plays a part, because it is almost 60kg lighter than the CX15 on the heavy-duty TGS 35.400 featured in last week's test.

All in all, this TGS 32.400 proved to be 720kg lighter than the 35.400, nearly 600kg less than the Scania and 840kg lighter than the Volvo. That's a significant bonus in its earning power, but evidently not the be all and end all: more than 60% of the MAN 8x4 chassis registered last year were heavy-duty 35 models rather than the lighter 32 chassis.

The 10.5-litre engine gives away more than two litres to its two rivals, but its power (394hp) and torque (1,900Nm) are far better than the modest displacement suggests. In fact, the MAN proved to be the quickest round our test route. It was noticeably rapid up the hills and it struck lucky at a couple of sets of traffic lights. It was a refined ride too, marred just a tad by what we felt was slightly stiff, unyielding coil-spring cab suspension.

Having already recorded a creditable 783mpg with the TGS 35.400, 8mpg was in our sights for the 32.400, bearing in mind that its direct-drive top gear and the singlereduction drive axles should both enhance fuel economy. So 758mpg was disappointing and almost certainly a reflection of the tightness of an engine and drivetrain that had covered fewer than 1,000km. The 35.400 had 16,000km under its belt, so we can only surmise that, given time, the 32.400 would loosen up and its economy would improve.

SCAN IA P360 Scania registered more 8x4 chassis last year than any other manufacturer, and the P360 was its most popular eightwheeler. Most have Scania's medium-duty chassis frame: made from 9.5mm-thick steel C-section, it is already rather more substantial than most others, so the reinforced heavy-duty alternative (300kg heavier) is rarely needed.

With 355hp and 1,850Nm of torque, the P360's 12.7-litre DC13 engine is below the class average in terms of output. Its 300rpm-wide peak torque plateau is also 25% narrower than its two rivals here. Unsurprisingly, the Scania was the slowest of the three trucks around the test route. The obvious solution is the P400, with 394hp and 2,100Nm. The trade-off for the slower journey time was the best fuel consumption, with an overall figure (fully laden) of 764mpg, just a whisker ahead of the MAN. It was particularly good on the Aand B-road section but the 8.69mpg motorway figure was just behind that of the MAN and the Volvo. Engine speed at 85km/h (53mph) is 1,365rpm, just past the end of the peak torque plateau at 1,300rpm, but still within the 1,100rpm to 1,500rpm green sector on the rev-counter.

The direct-top Opticruise 14-speed (12, plus two crawlers) automated gearbox is much improved since Scania ditched the clutch pedal. We judge its performance to be on a par with the ZF AS-Tronic in the MAN. Both the MAN and the Volvo were equipped with disc brakes all round, but Scania prefers to stay with less vulnerable drums for its construction trucks, supplemented by an exhaust brake linked to the brake pedal.

An unladen weight of 12,950kg with 300 litres of fuel on board leaves the Scania with a payload capacity of 19,050kg, almost 600kg less than the MAN. Much of that deficit is down to its BoweId MightyLite2 body, which is double-skinned not only on the sides but on headboard and tailgate too, preserving the exterior cosmetics. A single-skinned body — Boweld's MuckLite body, for example — would have boosted payload by around 500kg, putting the Scania within reach of the MAN.

It is a similar story with tipping gear. The Scania has Hyva's heavy-duty FC149 hoist, which is around 50kg heavier than the slimmer FC137 that could have been used. So in truth, the chassis-cab weights of these two trucks are far closer than our weighbridge readings suggest.

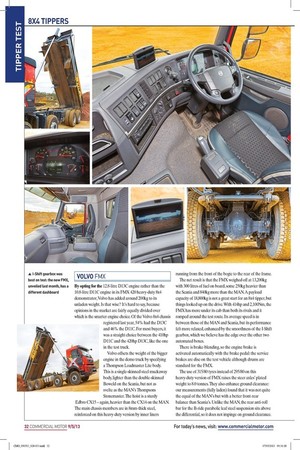

Even when fully laden there is huge ground clearance at the front — a drop of over half a metre from the bottom step can catch you unawares — but there is only half as much (250mm) beneath the differential casings, the smallest we measured. Externally, Scania's short cab is the shortest of the three vehicles, but the internal length is not so bad, and storage space behind the seats is virtually on a par with that of the MAN. I VOLVO FMX By opting for the 12.8-litre D13C engine rather than the 10.8-litre D11C engine in its FMX 420 heavy-duty 8x4 demonstrator,Volvo has added around 200kg to its unladen weight. Is that wise? It's hard to say, because opinions in the market are fairly equally divided over which is the smarter engine choice. Of the Volvo 8x4 chassis registered last year, 54% had the D13C and 46% the D11C. For most buyers, it was a straight choice between the 410hp D11C and the 420hp D13C, like the one in the test truck.

Volvo offsets the weight of the bigger engine in the demo truck by specifying a Thompson Loadmaster Lite body. This is a single-skinned steel muckaway body, lighter than the double-skinned Boweld on the Scania, but not as svelte as the MAN's Thompsons Stonemaster. The hoist is a sturdy Edbro CX15 — again, heavier than the CX14 on the MAN. The main chassis members are in 8mm-thick steel, reinforced on this heavy-duty version by inner liners running from the front of the bogie to the rear of the frame.

The net result is that the FM IX weighed off at 13,200kg with 300 litres of fuel on board, some 250kg heavier than the Scania and 840kg more than the MAN. A payload capacity of 18,800kg is not a great start for an 8x4 tipper, but things looked up on the drive. With 414hp and 2,100Nm, the FMX has more under its cab than both its rivals and it romped around the test route. Its average speed is in between those of the MAN and Scania, but its performance felt more relaxed, enhanced by the smoothness of the I-Shift gearbox, which we believe has the edge over the other two automated boxes.

There is brake-blending, so the engine brake is activated automatically with the brake pedal: the service brakes are disc on the test vehicle although drums are standard for the FMX.

The use of 315/80 tyres instead of 295/80 on this heavy-duty version of FMX raises the steer axles' plated weight to 8.0 tonnes. They also enhance ground clearance: our measurements (fully laden) found that it was not quite the equal of the MAN's but with a better front-rear balance than Scania's. Unlike the MAN, the rear anti-roll bar for the B-ride parabolic leaf steel suspension sits above the differential, so it does not impinge on ground clearance. The FMX's fuel consumption around our test route, 744mpg, was just a shade behind its two rivals. The deficit was greatest on the Aand B-road section, whereas motorway economy was comparatively better.

A few weeks after we conducted this test, Volvo unveiled its new FMX at the huge Bauma construction machinery trade show in Munich. Doubtless it includes similar revisions inside the cab to those we have just seen for the FM, so that means a new dashboard and seats. The latter have slightly thinner backrests, releasing a bit more stowage space behind the seat in the FM X's day cab. This is sorely needed because, although the cab is longer on the outside than Scania's, we measured less space behind the driver's seat.

The engine tunnel is rather high (430mm) and looks 'busy' because it is stepped rather than flat. The protruding centre console of Volvo's wraparound dashboard also eats into the space. At least the monitor for the reversing camera takes up no room at all because it pops up from the top of the dashboard.

A FEW THANK YOUS Our thanks go to Smiths of Bletchington, in particular to transport manager Paul Needle and quarry foreman Alan Johnson, for kindly hosting our testing at the company's Duns Tew quarry. Thanks also to Renault Trucks for providing its hospitality trailer as our operating base.

Conclusion It is not easy to separate these three. There is just 0.2mpg difference in their fuel consumption, insufficient to consider fuel economy as a major differentiator. However, common sense suggests that the MAN, once run in, could turn in a rather better figure. One also has to factor in the small additional cost of Ad Blue for the FMX, the only one of the trio to need it.

MAN has made an effort to achieve a good payload on its 32.400 demonstrator, choosing a lightweight body and hoist. We believe that if Scania had adopted a similar strategy for its P360 it could have cut its tare weight down to within 100kg of the MAN's. That would be a commendable achievement, considering the Scania has a 12.7-litre engine and a considerably chunkier chassis frame than the MAN.

After making allowances for differences in the body and hoist specifications, we calculate that the Volvo FMX chassis cab is 600kg-700kg heavier than its two rivals. And that is with non-standard disc brakes, which save around 100kg. The consequential loss of earning potential is indisputable; the debatable point is whether this additional weight necessarily results in a demonstrably more durable truck.

The Volvo driving experience was the best of the bunch, but not to the degree that makes up for losing so much payload, in our opinion. That leaves a straight choice between the MAN and the Scania. The latter is clearly the market's favourite, with a reputation for toughness and reliability in arduous conditions. On the other hand, we found the MAN's power and torque advantage meant that it was measurably faster than the Scania around our test route. We also appreciated the extra space in the bigger TGS cab.

Picking a winner between the Scania and the MAN depends on how these different strengths are prioritised. However, we suspect that differences in their road performance are likely to be outweighed by local factors such as the service level and competency of the dealer, maintenance costs and, of course, the overall financial package on offer.

Whichever emerges as the winner of such a comparison will have to be good to take on the fresh challenge that is sure to come from new models such as the Mercedes Arocs and Daf's revised CF85. Both offer punchy, new weight-saving 11-litre Euro-6 engines that are promised to be significantly more frugal than 13-litre Euro-5 models. A Euro-6 emissions reduction kit for an eight-wheeler is reckoned to add at least 200kg of extra weight, nibbling away at a truck's earning power. Tipper operators are relying on truck manufacturers to find the smartest ways to offset that.