When did you last see a brokendown fire engine?

Page 36

Page 38

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE PROVISION of a fire fighting service in one of Europe's busiest and most traffic-congested cities poses its own special problems. The repair and maintenance of the vehicles used in that service is one vital part of the solution, but is one of which the general public is rarely made aware.

Probably everyone who lives in the Greater London area, which includes 115 boroughs and covers some 635 square miles, will have seen and/or heard a London Fire Brigade appliance on its way to or from an emergency. But how many have seen one of those appliances broken down at the roadside or on the end of a towbar?

Vehicle and equipment reliability of the highest order, which is so essential for the efficient operation of a fire service, does not just happen. It has to be planned and maintained, and some of these vehicles' duty cycles do nothing to make that task easy. They would be described by the fleet engineer of many a general haulage fleet as downright mechanical abuse.

One example is the uncommon thermal stress to which a fire appliance's engine is regularly subjected — starting from cold and immediately being taken up to full power for perhaps only a matter of minutes before being left to idle, or used to drive pumping equipment. It is clear that this sort of treatment would also play havoc with manual gearbox and clutch life.

That is why the majority of the London Fire Brigade's 620strong fleet, which includes 389 fire appliances and 231 ancillary vehicles (including 118 cars), is now fitted with Allison automatic transmissions.

"We are just getting rid of the last of our manual gearboxes. Our replacement programme began seven years ago", brigade engineer, Roy Burroughs, told me.

And which engines do the UK's largest fire engine specify? The answer is "by and large, Perkins".

With some 450 Perkins engines in the fleet, the London Fire Brigade probably has more than any other single operator in the country. Most of them are V8 models from emitting a lot of dirty exhaust smoke when cold.

"We have tried using engine block water heaters, as many brigades still do," said Ken Hunt, "and they make no difference". He regards them as being "not worth the extra expense and complication. They just add another potential electrical problem, and with modern engine oils they should not be necessary. In any case, all the appliances are garaged in relatively warm fire stations overnight."

Roy Burroughs expects his engines to last the life of the vehicles. There is no policy, for example, to remove cylinder heads at a certain mileage or overhaul engines at another.

A high-mileage fire appliance in Greater London will cover around 10,000 miles a year, perhaps as much as 12,000 in a few exceptional cases. At the other extreme, one operated in Inner London will clock up only two or three thousand miles a year.

If an engine's performance deteriorates to the level where its oil consumption is unacceptably high, or its power output is insufficient to provide the acceleration demanded by the brigade and written into its specification, then it will probably be replaced by a service exchange unit. From a standing start a fully laden appliance with a warm engine must be able to reach a speed of 64.4krn/h (40mph) within 27 seconds.

The brigade's workshops and staff are certainly capable of overhauling engines, but the engineers have reached the conclusion that in most cases it is just not economical for them to do so, particularly now that manufacturers' exchange units are priced competitively.

Some engines have been replaced at what at first seems an unacceptably low mileage — 50,000. But then one needs to remember that they may have been in service for as long as 10 years.

At present GLC policy (and it is the Greater London Council which funds and controls the London Fire Brigade) is to replace pumping appliances after 12 years in service, lighter vehicles such as vans after seven years, and cars and carderived vans after five years. However, this policy is currently under review and it is possible that shorter working lives may be considered more economical in the future.

All vehicles are classified as either "first line" or "reserve and training". When a pumping appliance is about 10 years old it will be moved into the latter category, but it must be maintained in a thoroughly roadworthy condition right up to the time when a new appliance is allocated to the station concerned and the old one can be disposed of at a public auction.

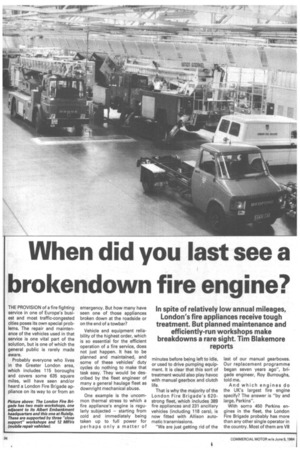

The headquarters of the London Fire Brigade and one of its main workshops is in Lambeth on the Albert Embankment. The brigade's four other workshops are at Barking, Croydon, Edmonton and Ruislip; the Ruislip site being the second main workshop, while the other three are "close support workshops".

The aim is to keep the appliances as close as possible to their areas of operation. It has been proposed that two more close support workshops, at Eltham and Kingston, are required to complete the ring around London.

Clearly the nature of the service provided by any fire brigade demands that vehicle availability be a high priority for the maintenance staff. Preventive maintenance is described by Roy Burroughs as "one of the cornerstones of the London Fire Brigade's maintenance philosophy". Each pumping appliance is brought into a workshop for an inspection at three-monthly intervals, and for a service and inspection at six-monthly intervals. Two examiners who report direct to the brigade engineer's office make random checks on vehicles to ensure that the system continues to be effective.

"The safety of brigade vehicles is our prime concern," said the brigade engineer.

But what about this key question of availability? It is a difficult enough job reconciling an effective preventive maintenance scheme with a transport manager's demand for vehicles to be on the road in a general haulage fleet. How much more difficult must it be to satisfy brigade officers who must want vehicles always ready to transport their men at high speed at a moment's notice?

Roy Burroughs confirmed that it was sometimes not easy to make brigade officers, who have little or no experience of running a fleet, understand his point of view. However, it is obvious that in general the working relationship between the 92 nonuniformed tradesmen who maintain the brigade fleet and their uniformed colleagues is a good one.

Officers' opinions on the vehicles they drive are taken seriously into account by the en gineering department. Roy Burroughs says his preventive maintenance system "starts with the driver".

When a breakdown does occur, the "first aid" will be administered by a mobile repair vehicle (MRV), which is based on a Dodge S56 high top van. The brigade has 12 of these, equipped to carry out minor repairs, at a fire station or at the roadside. At present they deal with about 350 vehicles a week, many of which require only minor adjustments, commonly brakes.

If the job goes beyond the capability of the MRV, the vehicle will be taken in to the nearest support workshop "on the run", that is with its crew, who will wait for it.

The two biggest unscheduled maintenance problem areas are brakes and accident repairs, both resulting mainly from the congested streets in which the appliances are operated and the way in which they have to be driven. An average annual tally for vehicle collisions of all kinds, from minor scrapes to serious damage, is between 800 and 850.

A hefty slice of the brigade's annual £1.2m maintenance and repair budget also goes on brakes, which seems likely to continue to be a problem until easy-to-maintain discs for commercial vehicles become more widely used.