What is Being Achieved by

Page 102

Page 103

Page 104

Page 105

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE MOTOR LORRY IN AGRICULTURE

Types of Vehicle Most Suited to the Different Needs of the Farmer and Small-holder. Classes of Transport Work Which Can Only be Tackled Efficiently by Means of Motor Vehicles.

EACH year as the Royal Show arrives we find the motor a little more firmly established in the agricultural industry. At the present time it is an essential part of the equipment of the industry. Now it is not, as it was a few years ago, a case of extolling the potential benefits of the motor in agriculture. The position has resolved itself into that of finding the right type of vehicle for the farmer's requirements.

The most widely used types of vehicle are the light tomer, the 30-cwt. lorry, or, at the most, a twotonner or 21-ton vehicle. Experience has taught the farmer that his lorry must be light and speedy and be equipped with pneumatic tyres. One of the essentials of farm transport is the ability of the vehicles used to travel on the land. Solid-tyred vehicles will not easily do this, and, in consequence, we find few of them in use. Pneumatics obtain by far a better grip when travelling on the soil.

The next consideration is that of body design, which depends entirely upon the nature of the agriculture carried on in any particular district. In market-gardening areas the design must be such as to allow the carrying of bulky loads, whilst in livestock and milk-producing districts the design must meet different needs.

There is another essential factor which a farm vehicle must possess, and that is speed. It is found that in general agriculture the swift vehicle is the most suitable, and by its wide adoption it has been proved that it is much more economical than the heavier and slower-moving type.

Farm lorries are mostly used for road work, in the same way as in every other industry, but they are not always able, as in most other cases, to start on a hard road. Farm economy to-clay must needs be studied to such a nicety that a lorry which requires hard ground on which to start is ruled out, because where a vehicle is used it does not pay to keep horses for the purpose of hauling crops from the fields to the road and re-loading them into the motor. Experience proves that the light pneumatic-tyred lorry up to about 30-cwt. capacity will haul a full load off the land under all ordinary conditions.

The 30-cwt. vehicle has been well tested as to its ability to obtain a grip on the soil when fitted with pneumatic tyres. There is no doubt about this, and any farmer buying such a vehicle can do so with full confidence. It is desirable to emphasize the fact, as it is one of the most important requirements in a lorry to be used principally for farm purposes. Many agriculturists are unaware of the capacity of the type 4:1. lorry we have mentioned to haul direct from the field.

The motor on the farm fulfils numerous purposes, the jobs it has to undertake being many and various'. In market-gardening, fruit-growing and the milk trade the factor of speed is c:)! paramount importance. Agriculture moves much faster than it did a few years ago and the speedy lorry has helped more than anything else to bring about this welcome change.

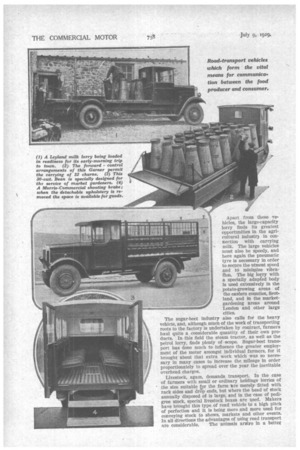

The aim to-day of every milk retailer is to deliver fresh milk in time for breakfast. This is not always done, but it is the object, and in a vast number of cases it is accomplished, the credit for which falls to the fast lorry or van, both in the retail and in the wholesale spheres. In the big milk-producing areas road transport has been developed greatly and many specially designed tank-wagons are in use. Apart from these vehicles, the large-capacity lorry finds its greatest opportunities in the agricultural industry in connection with carrying milk. The large vehicles must also be speedy, and here again the pneumatic tyre is necessary in order to secure the utmost speed and to minimize vibration. The big lorry with a specially adapied body is used extensively in the potato-growing areas of the eastern counties, Scotland, and in the marketgardening areas around London and other large cities.

The sugar-beet industry also calls for the heavy vehicle, and, although much of the work of transporting roots to the factory is undertaken by contract, farmers haul quite a considerable quantity of their own products. In this field the steam tractor, as well as the petrol lorry, finds plenty of scope. Sugar-beet transport has done much to influence the greater employment of the motor amongst individual farmers, for it brought about that extra work which was so necessary in many cases to increase the mileage in order proportionately to spread over the year the inevitable overhead charges.

Livestock, again, demands transport. In the case of farmers with small or ordinary holdings lorries of the size suitable for the farm are merely fitted with rack sides and drop ends, but where the head of stock annually disposed of is large, and in the case of pedigree stock, special livestock boxes are lased. Makers have brought this type of road vehicle to a high pitch of perfection and it is being more and more used for conveying stock to shows, markets and other events. In all directions the advantages of using road transport are considerable. The animals ariiie in a bettev condition and with less fatigue than when either taken by rail or walked by road.

In the neat trade the use of the motor is immense. Those who know anything of the prime Scotch beef that finds its way from the premier beef-producing area of Aberdeen will understand that the lorry plays a great part in connection with its marketing. The meat arrives dead at Smithfield Market, London, but the lorry is also used for carrying the cattle alive to the abattoir, from there to the railway station, and, again, at the London end. The practice of marketing meat dead instead of alive is likely, in the near future, to become more widespread, and in this work the motor has much to do.

All the same, the light, speedy lorry is the vehicle that puts money into farmers' pockets, and they know it. Each year witnesses an increase in the number of lorries used by individual agriculturists for the purpose of retailing produce. Each year sees an extension of mileage and an increase in the areas covered, and farmers who employ motors are to-day amongst the most prosperous. The strong tendency is for them to purchase and use their own vehicles.

Contracting in ordinary farming districts is not prominent. This fact is attributed to the need for each farmer to be dependent upon himself alone. He knows that a job must be done at the given moment. The transport of sugar beet is the only branch of farming which calls seriously for contractors.

Tractors, although gaining favour for land work, are not suitable for farm haulage in a general sense. They are quite satisfactory on the land, but for road work are not appreciated so much as would be expected.

Another point in connection with the use of motor vehicles for farming is the fact that agriculturists are not undertaking the maintenance of their own vehicles. They try to employ trained drivers who can carry out running repairs, but, apart from this, the major portion of the work is executed by the local garages. Many farmers drive their own vehicles, but, having the whole of their businesses to look after in addition, find leaving the work to the skilled mechanics at the garage much more to their advantage.

It is this fact that accounts for the development of a particular class of rural motor engineer whose shops, situated in the heart of farming country and equipped with spare parts and plant for the overhauling and repairing of lorries and tractors as well as threshing machines and, other farm implements, are well able to provide technical service for many land ho7dings situated around them.

The services they render are frequently of an inexpensive nature and the machines are again available for use in a reasonably Miort space of time.