LIGHT WEIGHT : LOW CO:

Page 128

Page 129

Page 130

Page 131

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By Laurence J. Cotto M.I.R.T.E. ASSUMING that the estimate of one mile on the M.1.R.A. circuit corresponds to 500-1,000 miles road work, the Atkinson-Willowbrook lightweight bus should have been creaking at every joint and ready for overhaul after 600 miles on the Belgian pave section. Except for a change of experimental rear-spring brackets early on, no breakage was experienced or other attention given, yet the bus ran smoothly and without trace of body movement to the end of these trials, after which it was passed to me for road testing. No replacements were required before being put into service, but, for passenger safety, the steering gear was changed.

Added to the exceptional performance put up by the Atkinson on the M.I.R.A. pavd, the machine proved most economical on the road, giving a fuel return of 19.33 m.p.g. for inter-urban work, and 18i m.p.g. when making one stop per mile. . It could not be expected that its acceleration rate, would compare with the largeengined single-decker on city service, because speed is usually obtained at the cost of economy.

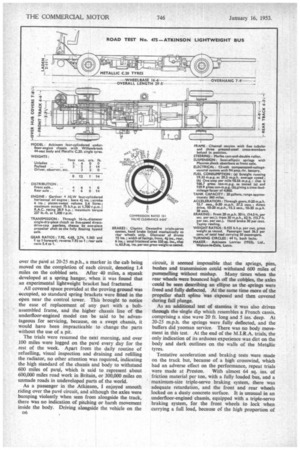

The lightweight model is a pared version of the Atkinson Alpha, and, having been built specifically with a view to economy of operation, weight has been reduced so that a reasonable performance can be obtained with a four-cylindered engine. In common with other Atkinson passenger chassis, a wide frame is employed, being inswept at the forward end to provide clearance for the wheels when on full lock.

The frame is made of material of lighter section than used on the contemporary models, the 4-in.-diameter cross-tubes for example being +-in. thick. To minimize floor height for a rear entrance, the frame side members are reduced at the overhang by 21 ins., a detail which contributes towards weight saving. Weight and cost are also reduced by fabrication of such parts as crossmembers, and spring and hanger brackets.

By careful arrangement of the components, the weight is almost evenly distributed between the axles, the same type of spring being employed at the front and rear, but with the addition of Monroe shock absorbers to help the front suspension. Because of the weight distribution, single tyres are used at the rear axle, but the track is 3i ins, less than at the front to avoid overloading the wheel bearings. Although the brake drums are part covered, ample surface area is exposed to aid cooling.

The Gardner engine, clutch and gearbox unit is supported forward of the frame centre, the drive being through a single mechanically jointed shaft to a light Kirkstall hypoiddriven axle. The engine is contained within the frame, with the crankshaft offset from the chassis centre line, but to avoid sharp angles in the transmission the axle drive unit is also arranged off centre.

°Mere should be no failures in the transmission, because the 16-in.

diameter clutch would stand almost 100 per cent. more torque than is produced from the four-cylindcred engine, and the David Brown 557 five-speed gearbox, with constant-mesh for all forward ratios, is similar to that fitted to a heavy service bus having a sixcy i ndered engine.

The Atkinson lightweight bus is

designed for a 30-ft-long 8-ft.-wide body, having an overall chassis length of 29 ft. 5 ins., and measuring 7 ft. 8+ ins, over the front-wheel hubs. Of 16-ft. 6-in, wheelbase, the front overhang of the chassis is 5 ft. 2 ins., leaving 7 ft. 9 ins, at the rear for a body entrance measuring up to 5 ft. 10 ins, in width. As a chassis the machine weighs 3 tons 14 cwt., and with the Willowbrook 44-seat body, the unladen weight of the complete bus is 5 tons 6 cwt., including a large heater unit fitted adjacent to the driver, behind the front panel.

From this it will be apparent that the Willowbrook stressed-skin all-metal body weighs 1 ton 12 cwt. complete with seats, air conditioning and heating units, and full-length parcel racks. All seats face forward, and with a single tyre of nominal dimensions, the wheel box intrusion into the body is less than normal at the rear. The method of attaching the body underframe to the chassis, through rubber-to-metal bonded units, possibly contributed to the performance put up at Nuneaton.

I took part in a test at the M.I.R.A. track, where the bus •was loaded with sandbags to represent 44 seated and six standing passengers. The Atkinson was driven o5

over the pave at 20-25 m.p.h., a marker in the cab being moved on the completion of each circuit, denoting 1.4 miles on the cobbled sets. After 40 miles, a squeak developed at a spring hanger, when it was found that an experimental lightweight bracket had fractured.

All covered space provided at the proving ground was occupied, so standard spring brackets were fitted in the open near the control tower. This brought to notice the ease of replacement of any part with a boltassembled frame, and the higher chassis line of the underfloor-engined model can be said to be advantageous for servicing, because, on a swept chassis, it would have been impracticable to change the parts without the use of a pit.

The trials were resumed the next morning, and over 100 miles were logged on the pave every day for the rest of the week. Apart from the daily routine of refuelling, visual inspection and draining and refilling the radiator, no other attention was required, indicating the high standard of the chassis and body to withstand 600 miles of pavi, which is said to represent about 600,000 miles road work in Britain, or 300,000 miles on unmade roads in undeveloped parts of the world.

As a passenger in the Atkinson, I enjoyed smooth riding over the pave circuit, and although the axles were bumping violently when seen from alongside the track, there was no indication of pitching or harsh movement inside the body. Driving alongside the vehicle on the D6 circuit, it seemed impossible that the springs, pins, bushes and transmission could withstand 600 miles of pummelling without mishap. Many times when the rear wheels were bounced high off the cobbles, the axles could be seen describing an ellipse as the springs were freed and fully deflected. At the same time more of the propeller shaft spline was exposed and then covered during full plunge.

As an additional test of stamina it was also driven through the single dip which resembles a French cassis, comprising a sine wave 20 ft. long and 5 ins. deep. At 20-25 m.p.h. the springs were fully deflected, and the buffers did yeoman service. There was no body movement in this test. At the end of the M.I.R.A. trials, the only indication of its arduous experience was dirt on the body and dark outlines on the walls of the Metallic tyres.

Tentative acceleration and braking tests were made on the track but, because of a high crosswind, which had an adverse effect on the performance, repeat trials were made at Preston. With almost 64 sq. ins, of friction material per ton, with a fully loaded bus, and a maximum-size triple-servo braking system, there was adequate retardation, and the front and rear wheels locked on a dusty concrete surface. It is unusual in an underfloor-engined chassis, equipped with a triple-servo braking system, for the front wheels to lock when carrying a full load, because of the high proportion of weight on the front axle. Taking the average of eight readings, when least wheel locking occurred, the bus was stopped in 30 ft. from 20 m.p.h., and 62 ft. from 30 m.p.h. Brake maintenance should be comparatively light in any kind of service, and with the adequate cooling of the rear drums, there should be little tendency to fade or for excessive pedal travel to develop when descending long declines.

Although I assess the acceleration rate as being good, considering the small power unit, 37 secs, from rest to 30 m.p.h: is a standard which will have tobe accepted by service drivers, some of whom will find a difference if they be accustomed to the heavier and more powerful buses. Obviously the difference in performance would be more noticeable in city operation, but for inter-urban work the Atkinson would not be at any great disadvantage.

This was apparent in the consumption trials, when driving at a nominal speed, the average for a 10-mile circuit was 29.2 m.p.h. without stops. In a second test over the same route, but with one stop per mile, the average speed, after omitting stationary time, worked out to 25.8 m.p.h. The advantage of the small engine is that once the bus is rolling freely in top gear, little power is required to keep it in motion, with resultant economy of fuel. During the continuous run, the consumption rate was 19.33 m.p.g., and 18.56 m.p.g., when making one stop per mile.

Although weight is pruned to align with engine output, the lightweight bus is sometimes at a disadvantage, when compared with contemporary models, in its hill-climbing performance. The ratios, in the Atkinson, for example, where a five-speed, direct-drive-top gearbox is employed, are arranged for any normal gradient to be tackled quite comfortably, although the time factor might be slightly longer than average. There was no difficulty in climbing Sheep Hill, a 1-in-9 gradient near Preston, but a lower ratio was required than when testing the six-cylindered Alpha on the same gradient. Alternative axle ratios are available; and with intelligent selection for the operating conditions, there might be little or no adjustment required to existing operating schedules.

Apart from those with inside knowledge, few passengers would know that there is any difference between the Atkinson lightweight and heavier-type of service bus. The sandbag load may have been contributory to reducing engine noise, but I myself found no undue vibration or distinctive characteristic denoting a fourcylindered engine when seated at the front or centre of the body. It w.as only at the rear, behind the exhaust tailpipe, that I found any difference, and then, at low engine speed, almost every exhaust stroke could be counted as the gases were expelled. Had the tailpipe been carried more to the rear, even this might have passed unnoticed.

The two days I spent on the bus were cold, with ambient temperatures of near freezing point, and I was grateful for the warmth of the Clayton heater in the body. Apart from the saloon, all other temperatures were low, the maxima recorded for the lubricants after average work, were 88 degrees F. for the engine and 93 degrees F. for the rear axle. Because of the shape of the radiator filler, it was not possible to insert a stick thermometer, but the top tank of the r4diator felt barely lukewarm. I think the addition of a thermometer in the water-cooling system-coupled with intelligent use of a blind and a screen to raise lubricant temperatures, would prove beneficial to fuel economy in winter. Undoubtedly, most unusual fuel returns will be obtained with the Atkinson lightweight bus.