The

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

.rt of

MANUFACTURING LEATHER CLOTH

IN these days when one hears so much about trade depression, it is refreshing to visit a factory which, on account of pressure of business, is working day and night, although it is equipped with all the latest kinds of labour-saving machinery. We found this to be the ease in the works of Rexine, Ltd., at Hyde, near Manchester, where leather cloth bearing that name is made.

The ever-increasing popularity of this product for covering seats, panels and for other uses in the construction of passenger-vehicle bodies, together with its hygienic properties, places it amongst the many interesting manufactures of components for vehicles.

Although the production of Rexine is a comparatively simple process, each step has to be taken with great care, and large and costly machines are necessary. Briefly, Rexine is a specially treated cotton cloth, coated on one, or both, sides with dissolved celluloid. Put in this form, its manufacture would seem to be a simple matter, but when the whole process is watched one realizes the great spare and capital outlay necessary for its production on a competitive basis. In the first place, it is essential, in order to fulfil orders promptly, to keep an immense stock of the cotton cloth of various widths and qualities. Some idea of the stock can be formed

from Fig. 4, which shows only a corner of the sheds in which a huge amount of cloth is at all times stored.

The first process to which the cloth is subjected is that known as "picking." This consists of spreading the material over large vertical boards, where it is examined by specially trained operators, whose keen eyes instantly detect blemishes in the form of knots, imperfectly spun threads, etc., which would interfere with the even laying of the coating, and which the operators remove with great dexterity.

The next process is performed by what is technically

known as a "raising machine." This is shown in Fig. 1, and consists of a big drum, which, as it rotates, carries with it a large number of rollers, each alternate roller revolving on its own axis, and in an opposite direction to its neighbours. These rollers are covered with what is known as "card," which is a stout woven fabric pierced with innumerable wire staples, the sharp ends of which have a scrubbing effect on the cloth, producing a matt surface similar to that seen on the reverse side of flexible leathers.

For certain reasons it is found advantageous to dye the cloth so that it matches the colour with which it is eventually to be coated.

Stentering is a process of stretching the cloth in all directions while damp and holding it in a stretched condition while it passes through a long, heated chamber until all moisture is driven from it. The object of the operation is to remove all folds and creases, so that it shall lie perfectly fiat in the machine that is to coat it with the cellulose dope, stentering being the last process through which the cloth passes while still uncoated.

The machines used for this purpose are extremely large on account of the length of material that they have to hold while it is being dried. The cloth passes from a roller to two sets of grippers which hold the edges of the cloth. Each of these grippers is mounted in a link of an endless chain, there being one gripper to each link. The chains extend for the whole length of the machine and travel over sprocket wheels at each end. As the cloth passes to the grippers they are held open by means of the bent rod shown in Fig. 4,

but when once the edge of the cloth is fairly well in and the grippers have passed the rod, the tongue of the gripper is allowed to fall, thus setting up a grip of the kind in which the harder the pull the tighter the hold, as shown in Fig. 7.

The two endless chains are set at such a distance apart that they will receive the cloth in its unstretched state, but the lines which the chains follow are not parallel. They slightly diverge for a short distance, thus stretching the material sideways, and then follow a parallel path while the cloth passes through a long, heated chamber which drives out all moisture and leaves the cloth free from creases and perfectly flat. At the end of this chamber, a rod opens the grippers to release the cloth, which is then wound on a roller and is ready for the coating process.

In the preparation of the cellulose dope, vast rows of mixing machines are to be seen stirring the material in its solvent, until it is completely dissolved, after which it is mixed with the various colours, these including every shade and range from white to black. The colouring matter is ground in oil and is so intimately mixed with the transparent base material that the colour is equally distributed throughout the mass.

While in this stage, if the material be touched by the finger, and the finger quickly withdrawn, a fine thread of cellulose will be produced, which resembles the threads forming artificial silk.

Mixing the colours to match the colour scheme of private cars and public passenger vehicles is an art in itself, and is carried out under the eye of an expert.

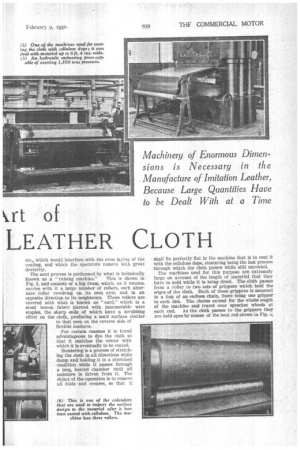

Coating the cloth is, perhaps, one of the most interesting processes in the production of Rexine. The machines used for this purpose are no less than 60 ft. long and are of sufficient width to deal with material up to 6 ft. 4 ins. wide. One of these machines is shown in Fig. 2. The cloth to be coated is introduced into the machine in the form of an endless band, the ends being sewn together so that the material can continuously pass through the machine until the desired number of coats has been applied. The number of coats may vary from six to 60.

The Coating Machine.

Our view shows the end of the machine at which the dope is applied, where the endless band of cloth passes around a large roller and over a bed, and under a blunt-edged scraper—the distance of the last-named above the bed determining the thickness of the coat. The dope is applied by means of a trowel to the space behind the knife, and is kept evenly distributed by the operator.

Fig. 8 shows in detail how this operation is effected, after which the cloth passes through the long, heated, vacuum chamber shown. Here the solvent is drawn n14 off by the vertical pipe appearing in Fig. 2, from which it passes to a condenser which restores it to its liquid form so that it can be used again. '

These machines can deal with as much as 600 yards of material at a time. The cloth is drawn by means of the roller at the rear of the machine, past the spreading knife and through the heated vacuum chamber, then passing in a looped form aleng the lower part of the machine until it reaches the front roller, from which it travels under the knife again until the desired number of coats has been applied. As many as 36 of these machines are employed in the plant of the company, working day and night.

Obtaining Special Effects.

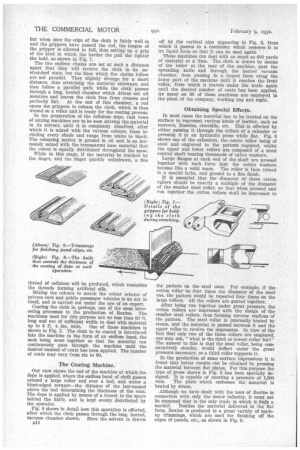

In most eases the material has to be treated on the surface to represent various kinds of leather, such as morocco, Russian, crocodile, etc. This is effected by either passing it through the rollers of a calender or pressing it in an hydraulic press while fiat. Fig. 6 shows one of the calenders, the centre roller being of steel and engraved to the pattern required, whilst the upper and lower rollers are composed of a stout central shaft bearing thousands of calico washers.

Large flanges at each end of the shaft are pressed together with such force that the cotton washers become like a solid mass. The roller is then turned in a special lathe, and ground to a fine finish.

It is essential that the diameter of these cotton rsillers should be exactly a multiple of the diameter of the smaller steel roller, so that when pressed and run together the cotton rollers shall be impressed to the pattern on the steel ones. For example, if the cotton roller be four times the diameter of the steel one, the pattern would be repeated four times on the large rollers. All the rollers are geared together.

After being run together under great pressure, the cotton rollers are impressed with the design of the smaller steel rollers, thus forming reverse replicas of the pattern. The steel roller is internally heated by steam, and the material is passed between it and the upper roller to receive the impression. In view of the fact that only two of the three rollers are employed, one may ask, "what is the third or lowest roller for?' The answer to this is that the steel roller, being comparatively slender, would deflect under the great pressure necessary, so a third roller supports it.

In the production of some surface impressions it is found that better results can be obtained by pressing • the material between flat plates. For this purpose the type of press shown in Fig. 3 has been specially designed. It is capable of exerting a pressure of 1,500 tons. The plate which embosses the material is heated by steam.

Although we have dealt with the uses of Rexine in connection with only the motor industry, it must not be supposed that is the only trade in which it finds a market. Besides the material delivered in the flat form, Rexine is produced in a great variety of madeup trimmings, which are used for finishing off the edges of panels, etc., as shown in Fig. 9.