Behind the fence in GM's proving ground

Page 34

Page 35

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

AT FIRST GLANCE there would appear to be no connection whatsoever between 700 acres of Bedfordshire countryside, Belgium and Edinburgh's Royal Mile. However, these three apparently unrelated items all come together at Millbrook, the proving ground of Vauxhall Bedford.

Here, hidden away from the prying eyes of competitors (and journalists!), Vauxhall cars and Bedford commercial vehicles are tested, modified, retested and so on in the never ending search for higher standards of reliability, durability and safety.

The giant General Motors organisation does relent on occasions and allows outsiders to visit Millbrook, so here is a CM guide to just what goes on behind the high wire fences.

Millbrook, some 18 miles from Vauxhall Bedford's Luton, includes a wide variety of test roads, special surfaces, hills and high-speed circuits.

Among the many "tools" available to the Bedford engineers are a 3.2km (two miles) five-lane circular high-speed track, miles of "A" and "B" classification roads, hill routes, fresh and salt water troughs, a dust tunnel, Belgian pave section and a crash test barrier.

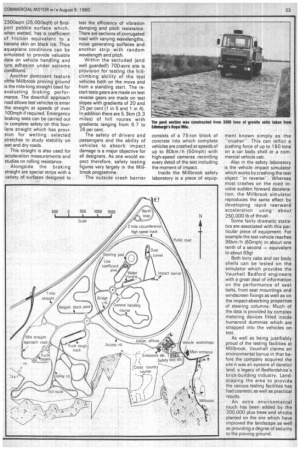

The Edinburgh-Belgium connection lies in the construction of the pave section. About 3500 tons of granite setts were ripped up from Edinburgh's Royal Mile when the city's trams were withdrawn. They were relaid by hand at Millbrook to make up the uneven bone-shaking surface of the 1.4km (0.9-mile) long Belgian pave section.

Although short, the pave circuit packs five bends including a 180' hairpin into its length.

Also designed to seek out the weak spots in suspension and chassis, the rough track is surfaced with irregularly spaced 225mm (9in) square concrete blocks, some of which are set 25mm (1in) high and some at twice this. This oval circuit 870m (2850ft) long is used for testing fully laden trucks only in contrast to the pave, which is also used for cars.

Also intended for lorry chassis only is the cross-country course which sorts out the strengths and weaknesses of the tipper models and the 4x4 military versions. Bedford has a long history of supplying vehicles to the armed forces.

The cross-country course is laid out on a hillside and includes a 2.4km (1.5-mile) section of really rough road with steep slopes and bends, mainly on unmade surfaces. Thrown in for good measure are rocky sections, muddy areas with deep potholes, a section of two inch setts and simulated ditch crossings.

Not all the tests are of the slow speed, poor road surface variety. The circular high speed track is 3.2km (two miles) in circumference and has five traffic lines plus an inner hard shoulder. The outer edge of the saucer-shaped circuit is 4.6m (1 5ft) higher than the inner edge with the contour of the track, being so constructed to give a neutral "hands off" speed for each lane. The outermost lane for example can be lapped at 160km /h (100mph) without the driver's hands on the wheel. The safe -hands off" speed for each lane is painted at intervals around the track.

Within the bowl of the highspeed circuit are located several of the other test facilities. These include iresh and salt water troughs, a dust tunnel and a steering pad with a special low coefficient of friction area.

Both the water troughs are 90m (300ft) long and one con

tains fresh water up to a depth of 1.2m (4ft). This is used for wading tests on the Bedford military chassis. The second trough contains salt water about one inch deep to reproduce the effects of winter motoring on roads spread with salt to clear ice and snow. In addition, a battery of nozzles directs salt spray over the sides of the test vehicle which in this case could be a Vauxhall car or a Bedford light van.

The dust tunnel enables the engineers to reproduce the conditions found in many of the less well-developed countries throughout the world. The 60m (200ft) tunnel has china clay dust laid on its floor; runs through prove the effectiveness or otherwise of door seals and similar items.

Steering characteristics of both cars and commercial vehicles can be studied on the steering pad, which has a diameter of 137m (450ft) and is slightly saucer shaped. The low friction area includes some 2300sqm (25,000sqft) of Budport pebble surface which, when wetted, has a coefficient of friction equivalent to a banana skin on black ice. Thus aquaplane conditions can be simulated to provide valuable data on vehicle handling and tyre adhesion under extreme conditions.

Another dominant feature ofthe Millbrook proving ground is the mile-long straight Used for evaluating braking performance. The downhill approach road allows test vehicles to enter the straight at speeds of over 100mph if required. Emergency braking tests can be carried out in complete safety on this fourlane straight which has provision for wetting selected stretches to study stability on wet and dry roads.

This straight is also used for acceleration measurements and studies on rolling resistance.

Alongside the braking straight are special strips with a variety of surfaces designed to test the efficiency of vibration damping and pitch resistance. There are sections of corrugated road with varying wavelengths, noise generating surfaces and another strip with random wavelength and pitch.

Within the secluded (and well guarded!) 700-acre site is provision for testing the hillclimbing ability of the test vehicles both on the move and from a standing start. The restart tests gears are made on test reverse gears are made on test slopes with gradients of 20 and 25 per cent (1 in 5 and 1 in 4). In addition there are 5.3km (3.3 miles) of hill routes with gradients ranging from 6.7 to 26 per cent.

The safety of drivers and passengers and the ability of vehicles to absorb impact damage is a major objective for all designers. As one would expect therefore, safety testing figures very largely in the Millbrook programme.

The outside crash barrier consists of a 75-ton block of concrete into which complete vehicles are crashed at speeds of up to 80km /h (50mph) with high-speed cameras recording every detail of the test including the moment of impact_ Inside the Millbrook safety laboratory is a piece of equip

ment known simply as the -crusher-. This can inflict a pushing force of up to 150 tons on a car body shell or a commercial vehicle cab.

Also in the safety laboratory is the vehicle impact simulator which works by crashing the test object -in reverse-. Whereas most crashes on the road involve sudden forward deceleration, the Millbrook simulator reproduces the same effect by developing rapid rearward acceleration using about 250,000 lb of thrust.

Some fairly dramatic statistics are associated with this particular piece of equipment. For example the test vehicle reaches 96km/h (60mph) in about one tenth of a second — equivalent to about 65g!

Both lorry cabs and car body shells can be tested on the simulator which provides the Vauxhall Bedford engineers with a great deal of information on the performance of seat belts, front seat mountings and windscreen fixings as well as on the impact-absorbing properties of steering columns. Much of the data is provided by complex metering devices fitted inside humanoid dummies which are strapped into the vehicles on test.

As well as being justifiably proud of the testing facilities at Millbrook, Vauxhall claims an environmental bonus in that before the company acquired the site it was an eyesore of derelict land, a legacy of Bedfordshire's brick-building industry. Landscaping the area to provide the various testing facilities has had cosmetic as well as practical results.

An extra environmental touch has been added by the 200,000 plus trees and shrubs planted on the site which have improved the landscape as well as providing a degree of security to the proving ground.