Steam and Oil in the Balance

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

We Draw Comparisons, In Respect of Torque and Tractive Effort as Related to Engine and Road Speeds, Between a Well-known Steam Lorry and a Typical First-class Oiler

CONCESSIONS in respect of gross weight limits are to be granted to steam vehicles; an announcement to this effect was made in The Commercial Motor dated March 12. Their object is to eliminate the disparity with regard to the respective pay-loads that steam and internal-combustion vehicles may carry, placing the two types on a more competitive basis.

The general pros and cons of solid and liquid-fuel-using vehicles are well known and the type that relies upon British coal as its source of motive power is favourably placed at the outset. We propose to consider actual road performances and, assuming that other matters are equal, to ascertain how the steam lorry compares with the oil-engined machine in respect of speed and hill-climbing characteristics.

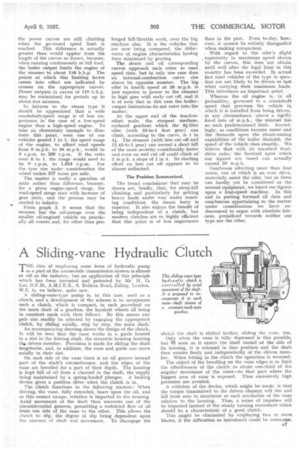

For this purpose, we have compiled sets of figures based on a modern Sentinel four-wheeler laden to a gross weight of 14 tons, which is the limit now proposed for four-wheeled steam vehicles, and two differently powered maximum-load four-wheeled oilers (gross weight 12 tons) with performances representative of first-rate quality in this field. From these, we have plotted graphs, from which comparisons can be made at a glance.

Graph 1 shows torque and b.h.p. against engine r.p.m., and graph 2 tractive effort in terms of lb. per ton gross weight against road speed. Our reason for considering tractive effort in lb. per ton is that the actual tractive efforts of the two types are not corn 13(1 parable, the steamer weighing two tons more than the oiler, when fully laden.

Corresponding gradient figures are also shown on the tractive-effort scale and, in arriving at these, a road resistance ranging from 24 lb. to 60 lb. per ton has been allowed. One authority gives 60 as the figure for wet well-rolled flint and gravel and 24 for macadamized road treated with tar. For purposes of comparison, the choice is arbitrary within limits.

The Tractive-effort Curves.

In the case of the steamer, there are three torque and b.h.p. curves, one for each of the three valve timings (afforded by the sliding camshaft of the S-type engine) for giving different degrees of expansive action of the steam. The transmission provides two gear ratios-4.56 and 12.45 to 1—so six tractive-effort curves are required. The two oil engines, which will be of about 7 litres and 8i litres capacity, are assumed to be installed in chassis having respective gear ratios of 7, 12.5, 21.5 and 35.6 to 1 and 6.5, 11.6, 20 and 33 to 1. Both types of vehicle are assumed to be equipped with 36 by 8 tyres, having an effective radius of 18.5 ins., and to have transmission efficiencies in direct drive of 94 per cent, and in indirect drive of 86.5 per cent.

Tractive effort is easily arrived at by multiplying torque by gear ratio by efficiency, and dividing by tyre radius. To convert gradient to tractive effort, the gross weight of the vehicle is divided by the number of units travelled horizorftally in rising vertically one unit, and to the result the resistance constant is added.

Referring to graph 1, the greater torque and power output of the steam engine are clearly shown, as is the higher crankshaft r.p.m. of the oil unit. The curves reveal clearly the well-known fundamental, distinctive characteristics of the two types. The one exerts its highest torque at very low r.p.m., whilst the torque of the other does not reach its maximum until about the middle of the crankshaft-speed range.

In fairness to the internal-combustion type, we draw attention to the wider speed range and to the fact that the power curves are still climbing when the governed speed Emit is reached. This difference is actually greater than would appear from the length of the curves as drawn, because, when running continuously at full load, the boiler output limits the engine of the steamer to about 110 b.h.p. The points at which this limiting factor comes into effect are indicated by crosses on the appropriate curves. Power outputs in excess of 110 b.h.p. may be maintained for periods up to about five minutes.

In fairness to the steam type it should be appreciated that a wide crankshaft-speed range is of less importance in the case of a low-speed engine than a high-speed engine. To take an elementary example to illustrate this point, were one of our vehicles geared 1 to 1, the speed range of the engine, to afford road speeds from 0 m.p.h. to 30 m.p.h., would be 0 r.p.m. to 2f39 r.p.m. If the ratio were 6 to I, the range would need to be 0 r.p.m. to 1,614 r.p.m. For the tyre size under consideration the wheel makes 54.-V7 turns per mile.

The matter is really a question of ratio rather than difference, because, for a given engine-speed range, the road-speed range rises with increase of gear ratio, and the process may be carried to infinity.

From graph 2, it seems that the steamer has the advantage over the smaller oil-engined vehicle on practically all counts and, for other than pro

longed full-throttle work, over the big machine also. It is the vehicles that are now being compared, the differepees of engine characteristics having been minimized by gearing

The steam and oil corresponding curves approach each other as road speed rises, hut in only one case does an internal-combustion curve rise above its opposite number. The big offer in fourth speed at 29 m.p.h. is just superior in power to the steamer in high gear with early cut -off, and it is of note that in this case the boileroutput limitations do not enter into the matter.

At the upper end of the tractiveeffort scale, the steepest mediumsurfaced gradient which the 84-litre oiler (with 33-to-I first gear) can climb, according to the curve, is 1 in 44. The steamer (with late cut off and 12.45-to-I gear) can ascend a short hill of the same severity considerably faster. and even on mid cut off could climb at 2 m.p.h. a slope of I in 4. Its starting effort on late cut off appears to he almost unlimited.

The Position Summarized.

The broad conclusions that may be drawn are, briefly, that, for steep-hill climbing and particularly for getting heavy loads under way under exacting conditions, the steam lorry is superior. It also enjoys the benefit of being independent of a clutch, but modern clutches are so highly efficient that this point is of less importance than in the past. Even to-day, however, it cannot be entirely disregarded when making comparison.

With regard to the oiler's slight superiority in maximum speed shown by the curves, this does not obtain until well after the legal limit in this country has been exceeded. In actual fact road vehicles of the type in question are not likely to be driven so fast when carrying their maximum loads. This introduces an important point.

Whereas the oil engine is, in all probability, governed to a crankshaft speed that prevents the vehicle in, which it is installed from being driven, in any circumstance, .above a rigidly fixed rate of m.p.h., the steamer has no such predetermined limit. Accordingly, as conditions become easier and the demands upon the steam-raising capabilities of the boiler diminish, the speed of the vehicle rises steadily. We believe that with its standard finaldrive ratio,' the Sentinel upon which our figures are based can actually exceed 50 m.p.h.

'Gearboxes affording more than four ratios, one of which is an over drive, materially assist the oiler, but as these can hardly yet be considered as the normal equipment, we based our figures upon a four-speed machine. In this and in putting forward all data and conclusions appertaining to the matter under consideration we have endeavoured to argue with absolute fair-mess, prejudiced towards neither one type nor the other.