ADAPTING THE DIESEL ENGINE TO ROAD USE.

Page 10

Page 11

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A Resume of the Problems Which Have to be Solved, and of the Progress Which Has Been Made.

TIOR MANY years past scientists in the labora tory, designers and engineers have been endeavouring to develop a Diesel or semi-Diesel engine light enough and sufficiently flexible to equal in its performance the petrol engine. There is no doubt that an enormous field exists for such an engine, which can make use of fuel practically impossible to employ in the ordinary internal-combustion engine.

Experimental power units of small sizes of the Diesel type were built even before the war, but not with any great success. However, the progress which has taken place during the past two or three years has been such as to merit more attention being devoted to the problem. Several engines have actually been fitted to motor vehicles, even to those employed in public service, as in the case of the Tartrais engine, which ran for some time in a Paris bus. Many experiments are also being carried out in Germany, and it is claimed that fairly successful results have been obtained.

In view of these points it will be of interest to refer to a recent article on the subject which appeared in our French contemporary, Le Poide Lourd, the author of the article being the engineer of the laboratory of L'Automobile Club de France.

This gentleman points out that the question of the application of the Diesel engine to road transport can be summed up by the following question : Is It possible to make a Diesel engine of comparatively small power light and durable? By small power is meant a motor of from 25 h.p. to 40 h.p., whereas the ordinary types range from 150 h.p. to 1,500 h.p.

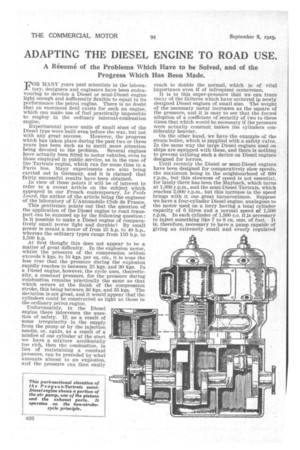

At first thought this does not appear to be a matter of great difficulty. In the explosion motor, whilst the pressure of the compression seldom exceeds 8 kgs. to 10 kgs. per sq. cm., it is none the less true that the pressure during the explosion rapidly reaches to between 25 kgs. and 30 kgs. In a Diesel engine, however, the cycle uses, theoretically, a constant pressure, for the pressure during combustion remains practically the same as that which occurs at the finish of the compression stroke, this being between 30 kgs. and 35 kgs. The deviation is not great, and it would appear that the cylinders could be constructed as light as those in the ordinary petrol engine. Unfortunately, in the Diesel engine there intervenes the question of safety. If, as a result of some irregularity in the supply from the pump or by the injection needle, or, again, as a result of a misfire of one cylinder at the start we have a mixture accidentally too rich, then the combustion, in lieu of maintaining a constant pressure, can be preceded by what amounts almost to an explosion, and the pressure can then easily reach to doilble the normal, which is of vital importance even if of infrequent occurrence. It is to this super-presusre that we can trace many of the failures which have occurred ip newly designed Diesel engines of small size. The weight of the necessary metal increases as the square of the pressure, and it is easy to see that the forced adoption of a coefficient of security of two to three times that which would be necessary if the pressure were actually constant makes the cylinders considerably heavier. On the other hand, we have the example of the steam boiler, which is supplied with a safety valve. In the same way the large Diesel engines used on Ships are equipped with these, and there is nothing to prevent utilizing such a device on Diesel engines designed for lorries. Until recently the Diesel or semi-Diesel engines have been designed for comparatively slow speeds, the maximum being in the neighbourhood of 600 r.p.m., but this slowness of speed is not essential, for lately there has been the Maybach, which turns at 1,300 r.p.m., and the semi-Diesel Tartrais, which reaches 2,000 r.p.m., but this increase in the speed brings with it one great inconvenience. Suppose we have a four-cylinder Diesel engine, analagous to the motor used on a lorry having a total cylinder capacity of 6 litres and a normal speed of 1,500 r.p.m. In each cylinder of 1,500 c.c. it is necessary to inject something like 7 to 8 cu. mm. of fuel. It is, therefore, necessary to have a pump capable of giving an extremely small and evenly regulated supply, for the least fault in the regulation will have a repercussive action relatively great. Also the system of mechanical pulverization does not seem to work very satisfactorily for small motors running at a high speed, and a second inconvenience is that the fuels employed are relatively viscous, and this viscosity incteases with the lowering of temperature ; in fact, it is impossible to employ them in winter without some system of preheating.

There is a third point, which also must not he neglected. Fuels such as Diesel oil are difficult to burn and, whilst this slow C'onabustion accommodates itself quite well to slow-speed engines, it is difficult to accelerate it in the case of engines which require a combustiion speed three times more rapid.

The best method of speeding up combustion is to increase the compression, but here we come to the same difficulty of unduly increasing the weight, and there is nothing left at our disposal than to increase the turbulence. From this point of view mechanical pulverization is very inferior to pneumatic injection.

One difficulty which does not always receive sufficient consideration is that of starting the motor. In the larger types compressed air is employed, but an air accumulator, again, adds considerably to the weight. Certain small fixed motors are arranged to be started by hand, as, for instance, the Hindi, this being done by employing a decompression device and a heavy flywheel, but on a lorry we cannot have a heavy flywheel. Suppose that by one artifice or another we can turn the motor at the same speed as that usually obtained at the crankshaft of an internal-combustion engine. Such a speed will be insufficient to permit starting, for, owing to its contact with cold surfaces, the temperature of the air which we have compressed will be inferior to that obtained during normal running. It is, therefore, necessary to adopt one of the three following remedies (a) A momentary super-compression.

(b) Some system of ignition, such as a metal spiral heated electrically until it is bright red.

(c) The employment of a lighter fuel.

As to the actual light Diesel motors which have been built, in Germany there are the Daimler, Benz and M.A.N. These were-exhibited at the Berlin Salon, but they do not seem to have emerged from their experimental stage. In France the Tartrais engine, after what appeared to be a most satisfactory start, has, at least for the time being, retirea into comparative oblivion. In CzechoSlovakia the makers of the Hindi, having finished their trials with a single-cylinder, have constructed a four-cylinder of 30 h.p. employing a four-stroke cycle.

Pneumatic injection is utilized in the Maybach, Daimler and the Hindi, whilst on the M:A.N. and the Tartrais mechanical pulverization is employed. The Benz is based on a principle analagous to that of the Brons.

In conclusion, although these light Diesel motors are of the greatest interest, and they are being studied to a certain degree almost everywhere, nowhere do we yet find practical application. Not one of these motors has really been placed on the market, in spite of the fact that they are certainly being awaited with impatience. At present it seems that in Germany the problem is the most advanced, but there, again, with the exception of one or two experimental engines, few practical results have been registered. In France, as a result of the efforts of certain designers, the study of the problem is being actively pursued, and it is probable, according to this authority on the subject, that it will not be long before it emerges from the stage of experiment.