With an almost 1,100kg payload, 2.5-litre turbo-diesel engine and all-terrain

Page 36

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

capability, the Land-Rover 110 pickup promises much — but, to some extent fails to deliver. On the rough, however, this marque is still supreme.

• There was a shuddering thwack as we hit the bottom of the rut. Try as we might, nothing stirred and we learned lesson number one.

If you are going to do some serious off-road driving with a standard-spec Land Rover 110 high-capacity pickup, either remove or raise the rear towing hitch. On our 110 is was mounted too low and severely reduced the vehicle's angle of departure. The towing hitch on our test vehicle had speared the ground like a tent peg, anchoring us to the spot.

Lesson number two was learned at the weighbridge. If you are going to push the Land Rover 110 pickup to its full 3,050kg gross vehicle weight by cramming around 1,100kg of payload on the back, watch your rear axle readings like a hawk: this vehicle is all-too-easy to overload.

With an unlevelled suspension system, the 110 pickup is plated at 1,200kg on the front axle and 1,850kg on the rear. We tried hard to load the vehicle evenly with 73 of our standard 15kg containers, trying every combination known to man before giving up with a rear axle reading of 1,960kg — 100kg over the legal limit. The solution was to take some of the containers out of the rear load space and stow them in the cab, piling the remainder against the low front bulkhead.

We finally achieved a proper axle reading with three containers stored in the passenger's footwell, forcing him to ride around with his knees under his chin.

Lesson number three was that once laden you have to take your time. The four-cylinder, 2.5-litre turbocharged diesel we had in the 110 took its time to get going, especially on the motorways and major A-roads of our fight-van test route around Kent and Surrey.

Our average speed was a shade under 63km/h (40mph) laden, compared with 70km/h in the vee-eight petrol-engined Land Rover 110 station wagon over the

same route (CM 21-27 January 1988); 691crnth from the Mitsubishi L200 pickup (CM 23-29 June 1988); 66km/h from the Peugeot 504 pickup (CM 11 April 1987); and 661tm/h from the crew-cabbed Volkswagen Syncro 4x 4 (CM 22 November 1986). Overall, the 110 high-capacity turbo-diesel pickup recorded one of the slowest average speeds to date.

The shortcomings of the four-cylinder 2.5-litre turbo-diesel engine have been noted before by Commercial Motor, not least its breathing difficulties and its lack of poke.

At the beginning of last year, we warned: "One of the major problems for Land Rover has been its perceived lack of power, particularly in diesel-engined form. Compared to the four-litre six-cylinderengine of the Toyota Landcruiser, or the three-litre Mercedes-Benz G-Wagen diesel, Land Rover's 2.5-litre four-cylinder unit is seen as being too puny." That is still the case today,

• DRIVELINE

In essence, the 2.5-litre Turbo D is an old design in modern garb. It is a turbo version of the 2.5-litre indirect-injection diesel Land Rover unveiled at the 1986 Motor Show with boosted power of 63.4kW at 4,000rpm and 203Nm (150Ibft) of torque at 1,80Orpm. A Garrett T2 turbocharger provides the extra push and the crankshaft is cross-drilled to ensure improved lubrication of the bearings.

The five-speed box is, like the curate's egg, good in parts. It seemed very tight to drive and needed a firm hand at all times, with first and reverse easy to confuse and select in error at the top lefthand corner of the gate.

Giving you the good news first, the engine is surpremely confident off-road, with excellent torque down to the bottom of the rev range. Engine braking down the steepest of gradients, even gravel-strewn alpine hills at the military test track in Bagshot, was superb. it felt in control all the time and the same was true in all the low ratio gears over the rough.

The transmission is flexible enough to pull away up steep 33% (1-in-3) gradient without a murmur and then power into the muddy sludge.

It is when the box goes on-road, into high ratio and onto big, straight highspeed roads that the bad news comes in. The unit rumbled like a doodlebug down the M20 and groaned up both test hills on our route, needing third gear in both cases to make it to the top.

The transfer box lever is small and stubby, mounted on the middle of the housing and requires demonic grip to shift. We had to push and pull like fury to find low ratio and thought the stick would snap before the difflock engaged and the light on the instrument panel came on to show things had dropped into place.

This is not a new fault on the Land Rover box. Many roadtesters over the years have complained that the unit is prone to drop into neutral just when you think it is in gear. The end-result, of course, is that you let up the clutch with the main box gear definitely engaged, lean forward to compensate for the rush of power, raise the revs and . . . nothing. Land Rover advises drivers to stop well away from steep descents to engage low ratio and the inter-axle difflock so that you can be assured everything is in place before it is too late. The company has heard this gripe before, it seems.

One final thought before we leave the driveline alone, Why is there no crossaxle difflock option, to help drivers out of the rut which everyone hits now and then? The 110 pickup has a long (2,794mm) wheelbase and we found that it bottoms out very rarely, but diagonally opposite wheels to tend to spin in tricky situations.

II PERFORMANCE

In a nutshell, the performance of the 110 is good off-road and dismal on-road. Fuel consumption is a poor 16.121it/100km (17.55mpg) laden, and 15.241it/100km (18.54mpg) unladen, with noise readings in the cab topping 84dB(A) in fifth gear.

Unladen, the 110 pickup is sprightly to drive. It holds the corners reasonably well with a tendancy to roll, but responds well at low speeds. When cruising, however, it takes time to wind up, and the vehicle lacks the energy for a long-haul slog.

Laden, the responses become more sluggish, the understeer becomes more exaggerated and the body-roll more noticeable. Snaking through the switchback on our test track fully laden was an interesting experience. We did not feel in danger of toppling and, to be fair, the tyres held their ground well, but there was a sense of being on the edge.

Braking was good and the parking-brake gripped like a boa constrictor on the measured inclines. All four tyres locked, however, on a dry test track from the lowest of rolling speeds.

Driven hard over loose gravel at our off-road and alpine test track, the 110 performed well. Different ratios suited different conditions and speeds, but it was almost impossible to fault the vehicle's ability to plunge and smash its way through the rough. Stopped half-way up the steepest 33% (1-in-3) gravel incline, the 110 slithered crablike without low ratio and difflocks engaged for the restart With everything in place, however, it crunched up the hill like it wasn't there.

The poor fuel consumption figures are near last year's 2.5-litre Turbo D roadtest on the 110 Station Wagon — with its much lower 850kg payload and 2,950kg GVW — when we recorded 14.41ft/100km (19.7mpg) laden. Farmers and major civil engineering contractors, however, will not worry too much about this sort of consumption, and the 110's undoubted strength off-road must surely remain its main attraction in this rough and tumble market.

• BODYWORK

The aluminium bodyshell remains Land Rover's trademark. Durable and light, the body sits astride a steel box-section chassis made to last.

The pickup loadspace has plenty of rope-lashing points and an optional canvas tilt. Once the tilt is fitted, it is difficult to tie things down inside because the rope lugs are all fitted to the outside edge of the pickup sides, so some interior lugs would not go amiss.

A ribbed load bed floor and bulkhead protection bars should help prevent some loads from sliding about, and our only other criticism is reserved for the locking bars on the rear tailgate. They are springloaded and need to he locked into place simultaneously, which requires the driver to stretch to both sides of the body when securing the back. Jane Fonda workout enthusiasts will love the experience; short plump truckers might find it a bit of strain. Watch your fingers too; they can get rapped all too easily.

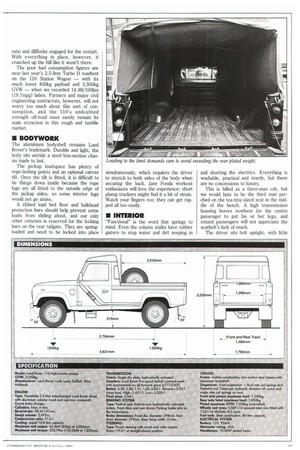

• INTERIOR

"Functional" is the word that springs to mind_ Even the column stalks have rubber gaiters to stop water and dirt seeping in and shorting the electrics. Everything is washable, practical and sturdy, but there are no concessions to luxury.

This is billed as a three-man cab, but we would hate to be the third man perched on the tea-tray-sized seat in the middle of the bench. A high transmission housing leaves nowhere for the centre passenger to put his or her legs, and rotund passengers will llot appreciate the seatbelt's lack of reach.

The driver sits bolt upright, with little travel on the seat to push away from the almost vertical windscreen and largediameter steering wheel. The dash and the windscreen seem uncomfortably close, which implies that the cab feels cramped. In fact this is not so headroom and legroom are plentiful.

A large speedo stares you straight in the face behind the wheel, and the fuel, temperature and battery gauges line up to its right.

There is also a full and illuminated instrument panel to tell the driver when four-wheel-drive has been selected, the difflock engaged and so on. The oldfashioned lift-up vents are still there behind the dashboard shelf and they still work well on a hot day. Demisting benefits from a strong fan and it is good to see that Land Rover doggedly retains the bolt-on, bolt-off approach to the cab. If it is hot, you can take virtually everything away. And why not?

Our 110 had a radio/cassette player which worked well, but had to boom like crazy to be heard above the engine and road noise above 50 or 60km/h.

The strangest sensation when driving the 110 is to suddenly corner hard to the right. The driving position, for three in the Cab, had been placed too far to the right and you feel like you are squeezed up against the offside door_ There is no elbow room at all to carry out a fast righthand-down manoeuvre, as you quiddy tire of rubbing shoulders with the door post and bumping arms and legs with the door at every turn.

Visibility is adequate, but with the canvas tilt fitted the rearview mirror has to peer through the murk of two perspex windows. The three-quarter lights at the rear are also blocked by the tilt, making pulling out of tricky T-junctions a bit of a guessing game.

• SUMMARY

We cannot imagine that any farmer or construction worker using the Land Rover 110 high-capacity pickup every day for work would quibble with the vehicle's selfassured off-road handling. We had to try hard to get it stuck, and good ground clearance, excellent low-down torque and first-class engine braking inspire confidence in the rough.

It is good value at £10,815 (ex-VAT) and Land Rover remains the four-wheeldrive market's yardstick. However, the 110 high-capacity pickup we tested was noisy, frequency uncomfortable, a bit too basic inside the cab, and heavy to steer on the open road with a somewhat lollopjug and lumpen feel.

The 110 would benefit from a more powerful and economic diesel engine, a brighter cab and better load space configuration. Perhaps it is now time for Land Rover to accept that even the best designs in the world can get dated.