ATKINSON

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 75

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

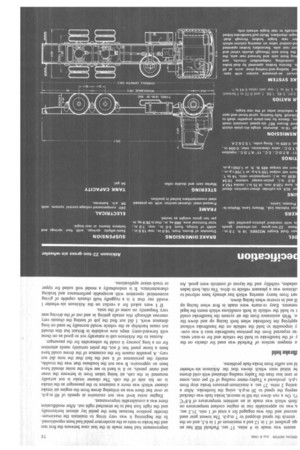

22-TON-GROSS

SIX-WHEELER

A. J. P. Wilding,

IlMechE, MIRTE FTHERE is no doubt that the higher weight limits permitted by the changes to the Construction and Use Regulations almost two years ago favour artics. At the time of the changes many people did not think much further than this, apart from accepting the extra figure of 2 tons gross allowed for some fourand six-wheelers and realizing that the eight-wheeler was not much better off, as the extra weight allowed had to be accompanied by disadvantageous length requirements. But in considering the changes now, it is apparent that there are many subtle implications and one of these is that the six-wheeler is much more of a proposition at 22 tons gross than it was previously, when limited to 20 tons.

Before the C. and U. changes the eight-wheeler had a 4-ton advantage over the six-wheeler, but to maintain this "gap" a 26-tongross four-axle rigid needs an outer axle spread of at least 23 ft.; many operators feel that this is not practical because of the reduced manoeuvrability that results. So the 4-ton advantage is reduced to 2 tons—and this includes an extra axle, so the net gain in payload is not much more than 1 or 1.5 tons.

Taking the Atkinson S.2266X which has just been subjected to a full road test as a typical example of current heavy-duty sixwheelers, this carried a load of about 15.75 tons, which is something like 10 cwt. less than that carried by comparable double-drive 24-ton-gross eight-wheelers previously tested by COMMERCIAL MOTOR. Taking into account the fact that the Atkinson was running at 13.75 cwt. over the 22 tons weight limit with nobody in the cab this means that as against a payload of about 14 tons

possible on a bodied 22 ton gross six-wheeler a similar 24 ton gross eight-wheeler can carry about 15 tons.

Whether it is worthwhile to pay for and carry around an extra axle for the sake of an extra 1 ton payload depends on the operator's requirements but going one further it can be shown that a six-wheeler like the Atkinson can take a similar payload to many four-axle artics running at 24 tons. But here other factors come in such as the extra platform length possible on an attic. However, the six-wheeler is certainly a very important class of vehicle and this is particularly so where conditions are arduous such as on tipper work or where site working is involved as with truck mixers. And for the haulier in hilly country where running in narrow lanes is involved the sixwheeler such as the test vehicle can be well worth while.

The results given by the model tested were generally very good and the vehicle performed very satisfactorily but one point was very noticeable. Loading. could be a problem as even with the test weights well away from the back of the cab the front axle was carrying almost 7 tons. As power-steering was not fitted on the test vehicle this resulted in very heavy steering. I consider this feature essential where the steering axle carries 6 tons or over and more important on the model tested as it was actually a tipper chassis and an evenly-spread load over the chassis frame would, I am sure, have given a front axle loading of about 8 tons. As well as powersteering, tyres having a greater capacity than the Michelin D2OX on the test chassis would appear to be essential.

The model S.2266X tested comes from the Atkinson Gold Knight range which includes four-, sixand eight-wheelers and is intended for tipper and truckmixer applications. The range is complementary to the Black Knight series offered by Atkinson for normal-freight haulage and for tanker use with which it is generally similar, the main differences being in the wheelbases offered andthe tipper models have a short rear overhang.

Gardner engines are used in all Gold Knight models in conjunction with David Brown gearboxes. The 5LW or 6LW engine and the 550 or 557/500 gearbox are fitted in the four-wheelers whilst the 6LX engine and 657 gearbox as in the test vehicle are used in all the sixand eight-wheelers. An Eaton two-speed rear axle is standard in the four-wheelers whilst Kirkstall axles arc fitted on the multiwheelers and there are singleand double-drive versions. In the latter case a lockable third differential is incorporated as standard. Gold Knight four-wheelers have a gross rating of 16 tons whilst the six-wheelers are produced for 20 or 22 tons gross but there are only 24 ton gross versions of the eight-wheelers.

The S.2266X chassis is of robust construction and the maximum frame section is 12.5 in. by 3 in. by 0.375 in. The front and rear springs are 3.5 in. wide and four-spring suspension (underslung springs) with balance beams is used at the rear. Interesting experimental fittings on the test chassis were lever-type dampers connected to each of the balance beams. These were being tried out to reduce axle hop when braking and as is described later in this report these were found to be very effective when the vehicle was unladen.

Braking system

The braking system used by Atkinson on the six-wheeler models is worthy of mention. This has a dual foot valve feeding independent circuits. One of them is connected to the front wheel brakes and the forward rear axle whilst the other feeds the front axle through separate pipework and a shuttle valve and the rearmost rear axle. For the secondary system required on plated vehicles a handreaction valve on the steering column powers the secondary side of dual-diaphragm chambers at the rear bogie brakes. The handbrake is a purely mechanical unit to the rear wheels but the test chassis had a new-design linkage with improved compensation to give more even effort at the four rear brake units.

First tests carried out were on fuel consumption and for these a 16.2 mile out-and-return trip on the A6 north of Preston was used. The road is typical of British main trunk routes and the figures ob

tamed should be repeated by the model when used on normal trunk haulage. Where empty return running is involved 11.8 m.p.g. should be obtained both for normal-speed and for high-speed running, this figure having been calculated from the actual fuel used on the full and empty runs. The figures are quite good and compare favourably with those obtained on previous tests of sixand eight-wheelers coming about halfway between the average for chassis to the previous weight limits.

The six-wheeler performed very well on the M6 motorway during the fuel consumption test between Bamber Bridge and the A5329 junction and return. For most of the 19.4 mile distance covered, the vehicle was at or near its maximum speed of 46 m.p.h. although the maximum obtained on overrun on one section was 53 m.p.h.

Although not having a sparkling performance the Atkinson gave reasonably good results on the acceleration tests and the times obtained are comparable with those of vehicles running at a similar weight on previous COMMERCIAL MOTOR road tests. Acceleration performance is naturally a direct function of power-to-weight ratio and in this respect the Atkinson is in line with current British thoughts of 6 b.h.p. per ton.

Initial brake tests that were carried out produced figures which were well below what I would have expected from an Atkinson chassis particularly as such excellent figures were obtained on my test earlier this year of an Atkinson 30 ton gross artic. This was so in respect of both stopping distance and the Tapley-meter readings. This part of the first day's tests was therefore abandoned with the promise from Atkinson that the vehicle would be checked over to see what was wrong. Nothing was, in fact, found to be wrong with the system but the brake linings were changed for Ferodo AM 11 which have been found by Atkinson to give many advantages including high efficiency, good fade resistance and not so liable to cause drum crazing.

Wet for re-test

With the Ferodo linings in use a re-test was carried out and in spite of very wet roads the reasonably good figures to be seen in the table were obtained. Brake balance between front and rear was good and rear wheel locking, inevitable in the circumstances, was accompanied by some front wheel locking. As is usual with four-spring balance-beam rear suspension the forward rear axle wheels locked for the greater part of the stopping distance which showed that the dampers fitted to the balance beam were having no great effect in this fully-laden condition.

But on the earlier test, brake performance had been checked in the unladen condition to examine the operation of this equipment. The dampers were found then to be very effective indeed in keeping all the wheels of the bogie on the ground during maximum-pressure brake stops. Obviously, all the wheels were locked but the vehicle kept in a reasonably straight line. With the dampers disconnected, however, there was a considerable amount of bouncing of the forward axle—the rearmost axle was locked and on the ground all the time—and this was shown up very clearly by the tyre markings on the road which was dry at the time. Although the dampers were an advantage in preventing hop and consequent "racking" at the rear end they had done nothing to reduce the stopping distance and actually increased it. About 6 ft. less was required to stop from 30 m.p.h. when the units were disconnected from the balance beams. Certainly the fitting of the dampers was proved to be a worthwhile thing.

On the brake re-test maximum Tapley-meter readings of 67 per cent were obtained on the stops from 20 m.p.h. and of 64 per cent from 30 m.p.h., which are well within the requirements of the Construction and Use Regulations for plated vehicles. The efficiency of the secondary system was well up to standard with the Tapley-meter reading obtained being 36 per cent. A check of stopping distance for the secondary system resulted in a measurement of 46 ft which represents an actual efficiency of 29 per cent and illustrates a commendably low time lag in application. Handbrake tests were not so good, the Tapley-meter reaching only 7 per cent and therefore not recording. But, as is reported later on, the handbrake was found capable of holding the outfit on a 1 in 6.5 gradient when helped by the footbrake.

Parbold Hill was used to assess the hill-climb performance and here again an acceptable result was obtained. The 0.75-mile ascent was made in 4 mins. 57 sec. Parbold Hill has an tge gradient of 1 in 12 and a maximum of 1 in 6.5, and on the • stretch the speed dropped to 7 m.p.h. The lowest gear used second and this was engaged for a total of 1 mm. 31.2 sec. e, was no appreciable rise in engine coolant temperature on limb which was made at an ambient temperature of 8.8°C F). On a run down the hill in neutral, brake fade was checked eeping the speed to 20 m.p.h. using the footbrake. After a lasting 2 mins. 27 sec. a maximum-pressure brake stop from t.p.h. produced a Tapley-meter reading of 45 per cent, some er cent less than the Tapley reading obtained with cold drums he initial tests which shows that the Atkinson six-wheeler Id not suffer from brake-fade problems.

dbrake held

le steepest section of Parbold was used for checks on the y of the handbrake to hold the vehicle and for re-start tests. 'as expected from the previous handbrake tests it was corny impossible to hold the vehicle on the handbrake without applying the footbrake when both facing up and down the ie. With assistance from the air system the handbrake could t to hold the vehicle in both conditions which meets the legal rements. Easy re-starts were made in first when facing up ill and in reverse when facing down.

)art from heavy steering which has already been referred to akinson was a pleasant vehicle to drive. The ride, both laden unladen, visibility and the layout of controls were good. An improvement had been made in the last case between the first test and the brake re-tests as the accelerator pedal had been repositioned. In the beginning it was very tiring to maintain the maximumthrottle position because here the pedal lay almost horizontally and the right foot had to be stretched right out. After modification there was a considerable improvement.

Engine noise level was not excessive at speeds of 40 m.p.h. or over but there was an irritating drone from the engine air intake cleaner which was more a nuisance to the passenger as the intake is on his side of the cab. The cleaner intake is not actually mounted in the cab, air being taken from in between the inner and outer panels, so it is hard to see why the noise should have been so oppressive. It was not the loudness that was the trouble, mainly the persistence of it and the fact that the note did not vary. A possible reason for the existence of the drone could have been a loose panel but if not, the point certainly needs attention for on a long journey it could be unbearable for the passenger.

Access to the Atkinson cab is naturally not so good as on those with forward-entry steps now available in Britain but this should not cause hardship as the vehicle would normally be used on long distance work. 1 did not find the job of testing the chassis very onerous although this entails getting in and out of the driving scat very frequently on some of the tests.

If I were asked for a verdict on the Atkinson six-wheeler I would say that it is a ruggedly built chassis capable of giving economical operation with acceptable performance and braking characteristics. It is undoubtedly a model well suited for tipper or truck-mixer applications.