A schooling in fuellinc is a lesson to lesser

Page 20

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The most obvious way to cut fuel bills — one seldom tried — is training drivers to drive more economically. Ron Cater, Sale Development Manager of Volvo (Gt. Br.) describes how it's done

PERFECTION is sought by many but found by few. Engineering perfection has not yet been achieved and while unlimited funds enable design and development engineers to produce equipment which approaches excellence, the word "perfect" has yet to find its niche in engineering circles, even those of the space programmes.

In the comparatively mundane diesel engine fields, however, where unlimited funds are most certainly not available, the search for relative perfection goes on all the time, but whatever level of perfection is achieved by the makers, the ultimate performance results, with regards to reliability and economy, rest with the operator and his maintenance and driving staffs.

For the purposes of this article, let us suppose that we have the best equipment that can be produced and that our operational methods and our maintenance is irreproachable. That leaves us at the mercy of our drivers.

The diesel engine manufacturers know very well that with the continuing escalation of fuel costs, the most urgent need of the user is to reduce consumption.

Fuel is currently accounting for some 22 per cent of operat ing costs and even savings of the single percentage order can represent enormous amounts of hard cash at the year end.

A 50 vehicle fleet covering an average annual mileage of 70,000 with an average mpg of 6.5, will use 538,461 gallons of fuel and at £1.50 a gallon that is £807,692. A 0.5 mpg improvement in comsumption in that fleet represents an overall reduction of 7.14 per cent in costs, amounting to a saving of over £57,000.

That amount of profit would warrant a fair sized effort in any other branch of a company's activities, but sadly few hauliers seem prepared to help their fuel consumption by setting time aside for proper training.

Interestingly, it has been our experience at Volvo that once consumption is reduced, so is wear and tear.

What then are the areas of improvement that we can take advantage of?

First we must decide whether the driver can improve his results.

If we are forcing the pace of operation so that only flat-out driving is acceptable, then no amount of driver education is going to make one jot of a difference to fuel consumption rates. Any vehicle driven to its limits all the time will use maximum amounts of fuel.

The reductions in operating speeds needed to bring the consumption figures to an acceptable level are not drastic and it is fair to say that they soon become unnoticeable.

The second step then is to make driving staffs available for training. In our training sessions at Volvo we do not aim to teach professional drivers how to drive but rather to understand how a vehicle uses fuel and what actually causes it to use more than it needs to.

Generally we have found that drivers think that when you ask them to drive more gently, you are asking them to drive more slowly. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact we have proved on many occasions that the problem lies not in "How fast you drive" but in "How you drive fast."

Violent acceleration, speed in the wrong situation, failure to read traffic and topography, failure to make use of the energy stored in the form of inertia in the vehicle are among the gre est consumers of fuel.

So we need to impart the c tam n knowledge to a driver tha he substitutes our methods handling a vehicle for Imethods, then the outcome v be an improvement in ti vehicle's fuel consumption.

However, we must not ev consider that we can train evt driver to a higher level of co petence, for that final outcomE totally dependent on the level which we start. During the fi years I have had the responsit ity for this type of training, I ha found it impossible to impro drivers, consumption perfor ances in some cases. In ma other cases the improvemE had been quite small, 1 or 1 per cent.

But there have been the grE majority of instances where ii provement has ranged betwe 3 and 15 per cent and final where we have achieved ii provements in the region of per cent.

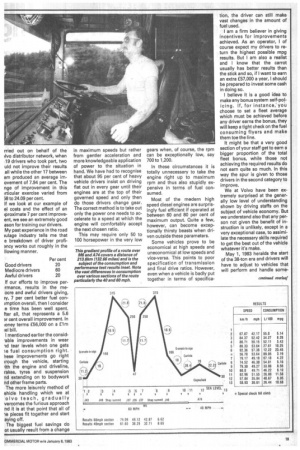

A typical result is oi achieved during an exercisE rried out on behalf of the ilvo distributor network, when 19 drivers who took part, two uld not improve their results all while the other 17 between ern produced an average imovement of 7.94 per cent. The nge of improvement in this irticular exercise varied from 58 to 24.09 per cent.

If we look at our example of el costs and the effect of an proximate 7 per cent improveent, we see an extremely good ason for training our drivers. My past experience in the road iulage industry tells me that e breakdown of driver profiancy works out roughly in the llowing manner.

Per cent Good drivers 20 Mediocre drivers 60 Awful drivers 20 If our efforts to improve permance, results in the meocre and awful drivers giving, 7 per cent better fuel conimption overall, then I consider le time has been well spent. fter all, that represents a 5.6 or cent overall improvement. In ioney terms £56,000 on a Elm lel bill.

I mentioned earlier the consid-able improvements in wear -id tear levels when one gets le fuel consumption right. hese improvements go right irough the vehicle, starting rith the engine and driveline, rakes, tyres and suspension nd extending on to bodywork nd other frame parts.

The more leisurely method of ehitle handling which we at olvo teach, gradually verconries the furious approach nd it is at that point that all of le pieces fit together and start eying off.

The biggest fuel savings do ot usually result from a change in maximum speeds but rather from gentler acceleration and more knowledgeable application of power to the situation in hand. We have had to recognise that about 95 per cent of heavy vehicle drivers insist on driving flat out in every gear until their engines are at the top of their governed speed and only then do those drivers change gear. The correct method is to take out only the power one needs to accelerate to a speed at which the engine will comfortably accept the next chosen ratio.

This may require only 50 to 100 horsepower in the very low gears when, of course, the rpm can be exceptionally low, say 700 to 1,200.

In these circumstances it is totally unnecessary to take the engine right up to maximum rpm and thus also stupidly expensive in terms of fuel consumed.

Most of the medern high speed diesel engines are surprisingly fuel efficient if operated at between 60 and 80 per cent of maximum output. Quite a few, however, can become exceptionally thirsty beasts when driven outside these parameters.

Some vehicles prove to be economical at high speeds and uneconomical at low speeds and vice-versa. This points to poor specification of transmission and final drive ratios. However, even when a vehicle is badly put together in terms of specifica tion, the driver can still make vast changes in the amount of fuel used.

I am a firm believer in giving incentives for improvements achieved. As an operator, I of course expect my drivers to return the highest possible mpg results. But I am also a realist and I know that the carrot usually has better results than the stick and so, if I want to earn an extra £57,000 a year, I should be prepared to invest some cash in doing so.

I believe it is a good idea to make any bonus system self-policing. If, for instance; you choose to set a fleet average which must be achieved before any driver earns the bonus, they will keep a tight check on the fuel consuming flyers and make them toe the line.

It might be that a very good section of your staff get to earn a bigger proportion of the total fleet bonus, while those not achieving the required results do not earn quite so much. In this way the spur is given to those drivers in the second category to improve.

We at Volvo have been extremely surprised at the generally low level of understanding shown by driving staffs on the subject of vehicle economy. But we understand also that any person not given the benefit of instruction is unlikely, except in a very exceptional case, to assimilate the necessary skills required to get the best out of the vehicle whatever it's make.

May 1, 1983 heralds the start of the 38-ton era and drivers will have to adjust to vehicles that will perform and handle some what differently with the extra weight.

Are we as an industry going to follow our usual apathetic path of accepting the benefits of weight increase with little or no thought given to further education and warnings to driving staffs as to what is involved in the movement of the extra six tons gross?

Where a driver expects his 186.5kW (250hp) tractive unit to accelerate at the same rate as at today's 32 (and often less) tons, he will be disappointed, and will complain to the fleet engineer that his engine is flat.

If the driver is fortunate enough to get a 1983 machine with adequate power to keep up his usual pace, then watch out for fuel consumption it could nosedive and quickly destroy some, if not all, of the extra payload earnings. Although there will be an extra pair of brakes to arrest the increase in weight, there will also be a rise in maintenance costs.

Tyre costs will inevitably increase, and that increase will de pend on which configuration one uses. Furious driving, however, will cause a much bigger increase than necessary.

A cause of excessive fuel consumption which is often overlooked is incorrect axle alignment. When we are dealing with five axles instead of four, this subject will require even greater vigilance if it is not to be detrimental.

Inaccurate assessment of fuel consumption results are often the cause of much bad feeling, wasted time and effort. if you are keeping fuel records, make sui your recording equipment doing its job properly or prepared for a "wild goo; chase."

We have found that the pre ence of the fuel recording met+ in the cab ticking away thousandths of a litre with su prising rapidity when the pow is hard on has an extreme sobering effect on drivin habits.

Once a driver gets the me sage that he can often mainta the same speed with only ht' throttle opening and keep speed of the flow meter vn to one tick a second or reabouts instead of six or ht per second, we are some y towards winning our battle mprovement.

nother point to take account s the difference that topogramakes to fuel consumption. a journey on the gradient afile graph shows very arly how much the consump-1 varies along the route and Ives that one cannot expect same results from vehicles rying out different duties in 'erent parts of the country.

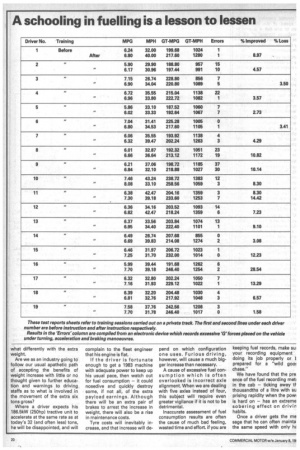

rhe table shows how difent the performance of driv; can be and how improved chnique will reduce the lount of fuel used without cessarily losing out on joury time to any significant dee.

fVe have already seen how a all improvement in each licle's consumption rate save, )ney. Two other advantages .mming from a quieter apaach to the job through drivmore gently could appear er some months of operation, wever, which might not at even be thought of.

kll of us who drive for busiss know what a stressful occuLion it can be. In days gone by, a truck driver much of that ess was contained by the hicle's maximum speed, for as one might even 40mph 'soften unattainable.

roday's vehicles however, are pable of speeds up to 75mph d the stress, although not adily noticeable, steadily ilds up into accident prone uations or even worse, into nor illnesses. Either is costly, iether through down-time for )airs or through shortage of if and the temporary replaceant of man or vehicle.

There is no doubt in our minds Volvo that training one's driv5 can result in quite substantial vings in fuel and other operanal costs.

The well-being of one's staff ght not rate very high as a St saving, but there can be no ,ubt that fitness is a prime rerirement for a lorry driver and become experienced one JSt remain fit for many years. Fuel consumption has, I beye, become the trigger for setg us off on the path of more lucated handling of our achinery. If we bite the bullet d take up the challenge of ucating our driving staffs, the suit must be better overall eco

■ rny and thus greater profitaity.