LINKING BRAKES WITH EUROPE

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A new EEC directive aimed at harmonising braking standards and equipment is causing some alarm, particularly where artics are concerned. Tim Blakemore reports

IN MAY last year we reported on mounting concern among fleet engineers over increasing brake maintenance costs, particularly on certain rigid vehicles. Now there is a fresh worry that brake maintenance costs may soon leap again, this time in the articulated vehicle sector.

International hauliers see another problem looming too — even greater incompatibility than exists at present between UK tractive units and "European" semi-trailers, and vice versa.

At the root of all these worries is the latest revision to EEC braking standards. The directive detailing these should have become available late last year, but still has not been published. It seems inevitable now that this delay will lead to a postponement of at least one of the three key implementation dates for the directive. The first of these allowing vehicles to be type approved to the new standard, was to have been April 1, this year. liowever, the technical requirements of the latest directive on braking have all been agreed and will certainly not be altered at this stage.

One of the most significant changes in

the new directive, which is based on ECE Regulation 13 05, is the requirement for higher retardation in the type approval test. The existing requirement for category N3 vehicles, goods vehicles above 12 tonnes gross, is that from a speed of 40km/h (25mph) the minimum average deceleration must be 80 per cent of 4.4m/sec2. The new regulation calls for a minimum average deceleration of 80 per cent of 5m/sec"E from an initial speed of 60km/h.

In terms of percentage braking efficiency 4.4m/sec2 is 45 per cent, while 5m/sec2 is 51 per cent.

The IRU (International Road Transport Union) is warning that the brake lining materials chosen by manufacturers to satisfy the new performance requirement may well wear at a faster rate than existing types. It also sees a potential increase in the risk of jack-knifing when a new tractive unit fitted with such linings is coupled to a semi-trailer with brakes designed to satisfy the current EEC law.

The IRU is not alone in wishing to see more attention paid by the legislators to the compatibility of tractive-unit and semi-trailer braking characteristics at the lower pressures which are much more commonly used. But the IRU does see real merit in the new provisions which relate to wet-weather braking performance. This, it says, will undoubtedly lead to an improvement in vehicles' all-weather braking performances.

The new EEC law will not affect the existing difference between UK operators and their mainland European counterparts on the subject of tractor/semi-trailer air-line connections. By and large, UK operators still prefer the three-line system, with a separate auxiliary line and two diaphragm brake chambers on the trailer, while the rest of Europe has long standardised on the two-line system.

Over the past few years, operators and vehicle suppliers have found satisfactory ways of matching the two. But now there is a new disagreement between the UK and our EEC partners on how tractive units and semi-trailers should be coupled. This time it is over the electrical connection for anti-lock systems.

Until now, EEC directives have not laid down in any detail the technical requirements for anti-lock systems. They have simply said that any voluntarily-fitted anti-lock must meet certain minimum construction and performance standards in the areas of failure warning, energy consumption, adhesion utilisation, and some additional checks.

The soon-to-be-published Annex 10 goes much further, for example by identifying three categories of anti-lock according to their degree of refinement of skid control. As you would expect, one of the subjects it also addresses is the compatibility of systems on tractive units and semi-trailers, the main aim being to avoid potentially dangerous combinations of and-lock and non antilock systems.

Despite scores of meetings between technical representatives from all EEC member states, complete agreement about electrical connectors has not been reached, although a compromise deal had to be struck to enable the directive to progress according to the timetable demanded by the EEC Commission.

Martin Manny, technical executive of the IRU, finds the compromise which has been reached wholly unsatisfactory. Fle says that it "jeopardises the interchangeability of all the EEC member states' vehicles with those of the UK." But as the country with more anti-lock equipped trucks in service than all others put together, the UK can argue from a position of special strength. About 80 per cent of new semi-trailers sold here now have antilock fitted.

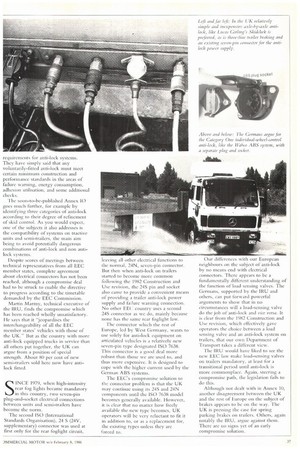

SINCE 1979, when high-intensity rear fog lights became mandatory in this country, two seven-pin plug-and-socket electrical connections between units and semi-trailers have become the norm.

The second ISO (International Standards Organisation), 24 S (24V, supplementary) connector was used at first only for the rear foglight circuit, leaving all other electrical functions to the normal, 24N, seven-pin connector. But then when anti-lock on trailers started to become more common following the 1982 Construction and Use revision, the 24S pin and socket also came to provide a convenient means of providing a trailer anti-lock power supply and failure warning connection. No other EE( country uses a second 24S connector as we do, mainly because none has the same rear foglight law.

The connector which the rest of Europe, led by West Germany, wants to use solely for anti-lock equipment on articulated vehicles is a relatively new seven-pin type designated ISO 7638. This connector is a good deal more robust than those we are used to, and thus more expensive. It is designed to cope with the higher current used by the German ABS systems.

The EEC's compromise solution to the connector problem is that the UK may continue using its 24S and 24N components until the ISO 7638 model becomes generally available. However, it is clear that no matter how freely available the new type becomes, UK operators will be very reluctant to fit it in addition to, or as a replacement for, the existing types unless they are forced to.

Our differences with our European neighbours on the subject of anti-lock by no means end with electrical connectors. There appears to be 3 fundamentally different understanding of the function of load sensing valves. The Germans, supported by the MU and others, can put forward powerful arguments to show that in no circumstances will a load-sensing valve do the job of anti-lock and vice versa. It is clear from the 1982 Construction and Use revision, which effectively gave operators the choice between a load sensing valve and an anti-lock system on trailers, that our own Department of Transport takes a diffi:rent view.

The IRU would have liked to see the new EEC law make load-sensing valves on trailers mandatory, at least for a transitional period until anti-lock is more commonplace. Again, steering a compromise path, the legislation rails to do this.

Although not dealt with in Annex 10, another disagreement between the UK and die rest of Europe on the subject of brakes appears to be on the way. 'Fire UK is pressing the case for spring parking brakes on trailers. Others, again notably the IRU, argue against them. There are no signs yet of an early compromise solution.