THE POSSIBILITIES OF THE

Page 106

Page 107

Page 108

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

UNORTHODO

'DESPITE official opposition the call for speed will have to be answered, with faster vehicles, even if it becomes necessary to rebuild the roads of this country in order to do so. Ia passing, it might be mentioned that the Minister of Transport recently gave brief details of the Government's five-year road plan. Arterial roads of the future should be quite safe for large passenger vehicles to operate at speeds up to 50 m.p.h., or even GO in.P.h., whilst correspondingly low speed limits would be required in towns. At the moment, almost any vehicle on the road can exceed the 30 m.p.h. limit by a substantial margin, but the 50 m.p.h. cruiser is not quite the everyday proposi tion some people would have us believe. It follows, then, that, assuming the road problem is removed, vehicles will have to be produced to run under conditions

which at the moment do not exist. .

The question now arises—will better roads call for better vehicles? Perhaps it would be better to put the question rather differently—will the removal of restrictions allow designers greater scope in the production of fast buses and coaches to operate Over long distances? The answer must be in the affirmative, despite the fact that modern vehicles of the class under review are highly efficient and are capable of very good road performances.

We now come to the crux of the matter. What are the lines on which such developments are likely to take place? If an improvement only in performance is demanded, one might be tempted to specify a larger engine for an existing vehicle as being a simple and easily achieved method of obtaining the desired high-performance characteristics which wide arterial roads would allow. This, however, is

not the whole story for, apart from anything else, the wsthetic side of the matter has to be considered and practical considerations regarding actual construction taken into account.

In the private-car world a great deal of attention is being paid to streamlining, and although from a performance point of view, there is little advantage to be gained, at any rate at the lowor end of the speed range, the designs of sour.: of the new cars embodying streamline principles are extremely attractive. It would appear to be not unreasonable to suppose that coaches could be produced with streamlined bodies which would be equally attractive. Indeed, many of the latest bodies are built with contours which suggest that the elementary principles of a free airflow have been taken into account so that, assuming speed restrictions are at some future 'date removed, passenger vehicles with smooth, tapering contours should eventually be evolved. Among the accompanying illustrations is an artist's impression of such a vehicle, and although there are points open to serious criticism, there is something of a pleasing nature about the design.

A Survival of the Earliest Days.

One cannot help but be impressed by the manner in which engine bonnets have persisted from the early days until the present time. Even now, when the reliability of both petrol and oil engines passes „unquestioned, acces sibility of the power unit• is considered as being of paramount importance. For that reason the off side of practically every erurfine is barren of auxiliaries, whilst the near side has the whole of the electrical gear, the fuel pump, carburetter, oil dip-stick and so forth grouped under the half bonnet, with a radiator of conventional form in front and an overhung structure to house the driver, on the right. Such a method of construction has little to recommend it, for it gives an awkward shape at the front and is wasteful of space which could easily be adapted to carry at leas' two additional passengers.

To alter this state of affairs means that the bonnet must be discarded and this, in turn, entails finding a new position for the engine. At least one maker has solved the problem by placing the power-unit along the side of the chassis, and according to reports, with every success.

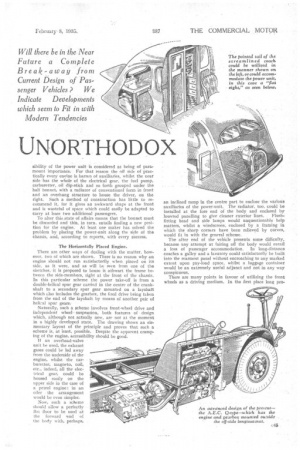

The Horizontally Placed Engine.

There are other ways of dealing with the matter, however, two of which are shown. There is no reason why an engine should not run satisfactorily when placed on its side, as it were, and as will be seen from one of the sketches, it is proposed to house it athwart the frame between the side-members, right at the front of the chassis. In this particular scheme the power take-off is from a double-helical spur gear carried in the centre of the crank1.-iaft to a secondary spur gear mounted on a layshaft which also includes the gearbox, the final drive being taken from the end of the layshaft by means of another pair of helical spur gears:• Naturally, such a scheme involves front-wheel drive and independent wheel suspension, both features of• design which, although not actually new, are not at the moment in a highly developed state. The drawing shows an elementary layout of the principle and proves that such a scheme is, at least, possible. Despite the apparent cramping of the engine, accessibility should be good.

If an overhead-valve

unit be used, the exhaust gases could be led away from the Underside of the engine, whilst the carburetter, magneto, coil, etc., indeed, all the electrical gear, could he housed easily On the upper side in the case of a petrol engine: in an oiler the arrangement would be even simpler...

Now, such a scheme should allow a perfectly flat floor to he used at the forward end of the body with, perhaps,

an inclined ramp in the centre part to enclose the various auxiliaries of the power-unit. The radiator, too, could be installed at the fore end of the body and enclosed by louvred panelling to give cleaner exterior lines. . Flushfitting head and side lamps would unquestionably help matters, whilst a Windscreen, enclosed by a. framing in which the sharp corners have been relieved by curves, would fit in with the general scheme.

The after end of the vehicle presents some difficulty, because any attempt at fairing off the body would entail a loss of passenger accommodation. In long-distance coaches a galley and a lavatory could satisfactorily be built into the rearmost panel without encroaching to any marked extent upon pay-load space, whilst a luggage container would be an extremely useful adjunct and not in any way conspicuous.

There are many points in favour of utilizing the front wheels as a driving medium. In the first place long pro puller-shafts are avoided, secondly, the floor height of the vehicle could be determined by the requirements of the body rather than by the height of the axle pot, as it is at present. Again, it is quite likely that a lighter chassis could be produced for a giVen strength by incorporating a. frame with outriggers to carry the body, the whole arrangement of the cross-members and so forth being a straightforward and simple matter. There is no need fer heavy members to be used, as driving shafts and gearbox supports are, of course, avoided.

Against the scheme is the reduced road adhesion of the driving wheels when climbing hills or accelerating, due to the backward movement of the centre of gravity. This transference should not be very great in either case, however, as commercial vehicles seldom climb exceedingly steep hills and the acceleration is also moderate.

A Flat Eight at the Rear.

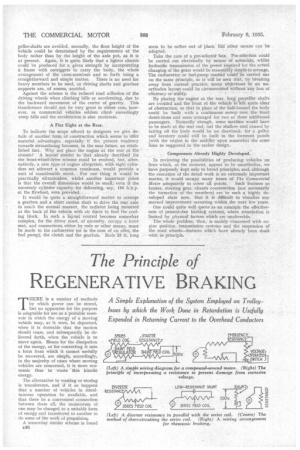

To indicate the scope offered to designers we give details of another form 0 construction which seems to offer material advantages, especially if the present tendency towards streamlining becomes, in the near future, an established fact.. Why not place the engine at the rear of the chassis? A layout similar to that already described for the front-wheel-drive scheme could be evolved, but, alternatively, 'a new type of engine altogether, with eight cylinders set athwart a common crankcase, would provide a unit of considerable merit. For one thing it would be practically vibrationless, whilst another important point is that the overall dimensions would be small, even if the necessary cylinder capacity for delivering, say, 150 b.h.p. at the flywheel, were provided..

It It would be quite a straightforward matter to arrange a gearbox and a short cardan shaft to drive the rear. axle in much the normal manner, the radiator being mounted at the back of the vehicle with air ducts to feed the cooling block. In such a layout control becomes somewhat complex, for the driver must, of necessity, occupy a front seat, aud connections, either by rods or other means, must be made to the carburetter (or in the case of an oiler, the fuel pump), the clutch and the gearbox. Rods 25 ft. long seem to be rather out of 'place; but other means earl:be , adopted.

Take the case of a pre-Seleetdi box.. Pre-selection could be carried out electrically bY Meansof solenoids, Whilst hydraulic transmission of the'power required for the actual changing of the gears would be reasonabl iiinple to arrange. The carburetter or fuel-pump control could be carried out on the same principle, so it will be seen that, by breaking away from current practice, many objec:tions to an unorthodox layout could be cireurnventect Without any loss of efficiency or utility.

By placing the engine' at the rear, long propeller shafts are avoided and the front of the vehicle is left quite clear of obstruction, so that in place of the half-bonnet the body could be built with a continuous sweep: ciVer the front dumb-irons and seats arranged for two or three additional passengers. Naturally enough, some sacrifice would have to be mad2. at the rear end, but the shallow roof caused by fairing oft the body would be no drawback, for a galley and lavatory could still be built in the foremost panels (with the engine in the middle). upon somewhat the same lines as suggested in the earlier design.

Components Already Highly Developed. .

In reviewing the possibilities of producing vehicles on lines which, at the moment, appear to be unorthodox, we have purposely kept only to broad principles, and, although the execution of the detail work is an extremely important matter, it would occupy many issues of The Commercial Motor adequately to cover all points. Such features as brakes, steering gear, chassis construction (not necessarily the formation of the members) arc in such a highly developed state now, that it is difficult to visualize any maraed improvement occurring within the next few years.

One could quite well quote as an example the effectiveness of present-day braking systems, where retardation is limited by physical-factors Whkh are unalterable.

The whole problem, then, is mainly' cbncerned with engine poSition, transmission systerns and the suspension of the road wheels—features which have already .been dealt with in principle.