LAND-ROVER 4 x

Page 56

Page 57

Page 58

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

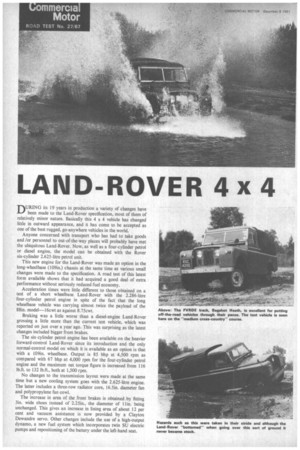

By A. J. P. Wilding, AMIMechE, MIRTE DURING its 19 years in production a variety of changes have been made to the Land-Rover specification, most of them of relatively minor nature. Basically this 4 x 4 vehicle has changed little in outward appearance, and it has come to be accepted as one of the best rugged, go-anywhere vehicles in the world.

Anyone concerned with transport who has had to take goods and /or personnel to out-of-the-way places will probably have met the ubiquitous Land-Rover. Now, as well as a four-cylinder petrol or diesel engine, the model can be obtained with the Rover six-cylinder 2.625-litre petrol unit.

This new engine for the Land-Rover was made an option in the long-wheelbase (109in.) chassis at the same time as various small changes were made to the specification. A road test of this latest form available shows that it had acquired a good deal of extra performance without seriously reduced fuel economy.

Acceleration times were little different to those obtained on a test of a short wheelbase Land-Rover with the 2.286-litre Braking was a little worse than a diesel-engine Land-Rover grossing a little more than the current test vehicle, which was reported on just over a year ago. This was surprising as the latest changes included bigger front brakes.

The six-cylinder petrol engine has been available on the heavier forward-control Land-Rover since its introduction and the only normal-control model on which it is available as an option is that with a 109in. wheelbase. Output is 85 bhp at 4,500 rpm as compared with 67 bhp at 4,000 rpm for the four-cylinder petrol engine and the maximum net torque figure is increased from 116 lb.ft. to 132 lb.ft., both at 1,500 rpm.

No changes to the transmission layout were made at the same time but a new cooling system goes with the 2.625-litre engine. The latter includes a three-row radiator core, 16.5in. diameter fan and polypropylene fan cowl.

The increase in area of the front brakes is obtained by fitting 3in. wide shoes instead of 2.25in., the diameter of 1 lin. being unchanged. This gives an increase in lining area of about 12 per cent and vacuum assistance is now provided by a Clayton Dewandre servo. Other changes include the use of a high-output dynamo, a new fuel system which incorporates twin SU electric pumps and repositioning of the battery under the left-hand seat. All Land-Rover models are now equipped with a re-styled instrument panel of the type fitted to the forward-control model and detail changes in the cab include a combined ignition /starter switch, lever-type control switches for the lights and so on. Also an extended handbrake lever provides for easier application by a driver wearing safety harness and twin wiper motors have been replaced by a single unit operating the twin blades through a concealed rack-and-pinion drive mechanism.

Before the normal road tests were carried out the test vehicle was taken to the FVRDE test areas at Bagshot Heath and Chobham to assess the performance in off-the-road conditions. This was intended primarily as an academic exercise, for previous tests of Land-Rovers—both longand short-wheelbase—have shown the model to be capable of taking most types of rough conditions in its stride and the changes made were not felt likely to produce problems.

But a problem did occur. Almost at the end of the tests on the arduous alpine and cross-country circuits, a water hazard was being negotiated at speed when water got in the engine, creating an hydraulic lock in the cylinders and we stopped dead.

We had been pushed out of the pond and were being towed back to the marshalling area when further trouble occurred. After about a mile a rear wheel came off and extensive damage was caused to the brake unit and hub in the 300 yards we travelled before the driver of the towing vehicle could be made aware that we wanted him to stop.

It was surprising that water got into the engine for although the air intake is close to the offside grille, under the headlamp, it is in this position on military applications and extensive tests were made to make sure that water does not enter.

After the wheel was repaired repeated runs were made through the same pond at different speeds, but there was no recurrence of the trouble. The only possibility is that a combination of speed, depth of water and the particular contour of the bed of the pond at one point caused a jet of water to be directed at the grille in front of the intake cleaner.

With regard to the wheel coming off, this again was most unusual. Vibration built up for some distance before the rear end of the Land-Rover dropped, and if I had been able to do so, I would have stopped to investigate.

A thorough check by Rover engineers failed to find any real cause for the nuts slackening, so the only explanation possible is that they were not tightened adequately when the Land-Rover was serviced before being supplied for• test. I am sure that this is the reason myself and I now check wheel nuts of all vehicles before I test them!

On the original test and on the repeat runs the Land-Rover performed well at Bagshot Heath. Like other examples tested it handled well on the rough ground with plenty of power to spare on the gradients of up to 1 in 2.65 on the alpine course.

Following the Bagshot Heath tests the Land-Rover was taken to the FVRDE, Chobham, for assessment over the suspension courses and test slopes. The test vehicle also performed well here. The two set tracks-1 to 1.5in. and 2 to 2.5in.—were driven over at 50 and 45 mph respectively and the severe pave was traversed at up to 40 mph. It is probable that 45 mph or so could have been reached on the pave but that could have been dangerous for men working by the side of the track. As with previous models tested the Land-Rover was easy to control at the speeds reached on the suspension courses and the chassis stood up well to the battering administered.

But on the test hills it soon became apparent that the handbrake was not in the best of health. It may have been a question of adjustment or due to water and mud getting into the drum-type transmission brake but the unit would not hold on a 1 in 3 gradient.

On previous Land-Rover tests the transmission brake has held the model on the 1 in 1.73 gradient at Chobham at a greater gross weight than on this test, so the design is basically sound. But having a reduced efficiency made completion of the hill tests impossible.

The Land-Rover was driven up the 1 in 1.73 in bottom/low to about the halfway point and although the impression was that it would surmount the hill comfortably, this was decided against as it would have been dangerous to get near the crest and then have fuel starvation or loss of adhesion or similar without a handbrake capable of holding the machine. As it was, the footbrake would not hold the vehicle when facing up the 1.73 and the run down the slope backwards was rather ticklish.

But here again the hill tests were of relatively academic

interest as the diesel-engine version of the model had completed the 1 in 1.73 climb with 23 bhp less power output.

Brake tests were completed while at Chobham and the figures were a little down on the previous tests due largely to persistent locking of the front wheels; increasing the front shoe sizes is a mixed blessing. The reason for the poorer figures could equally have been need for adjustment at the rear or mud in the drums. Maximum deceleration on the stops was 90 per cent from 20 mph and 80 per cent from 30 mph.

Acceleration tests were also completed at the FVRDE track and as expected extremely fast times were recorded. The 2.625litre engine was tractable in direct-drive and even fully laden, bottom gear was not always necessary for normal driving. Maximum speeds in the gears were 24, 39, 60 and 71 mph.

Fuel consumption checks were carried out over our usual route near Luton on A6. Figures obtained were reasonable. Driven carefully, it should be possible to obtain between 15 mpg and 20 mpg from the Land-Rover as tested depending on the degree of loading. When driven hard, however, consumption increased sharply, particularly when at high speed, and it is significant that the consumption while completing the tests at FVRDE and "pushing" the vehicle at other times on the day, always fully laden, a figure of 13.4 mpg was obtained.

Normally, trials on the FVRDE test hills are reckoned sufficient for hill-performance ability but with this test the normal hill-climbing check—on Bison—was carried out also. As will be seen in the table a very good time was put up for a maximum-power ascent although more fade than expected resulted from this test on the run down.

The cab of the Land-Rover still retains its workmanlike appearance but the recent changes have had the effect of tidying up the area in front of the driver. The change to switch-controlled wipers made for much easier control. Other switches are much better to operate and the handbrake is easy to apply. Seating is reasonably comfortable.

The basic price of the long-wheelbase Land-Rover with tilt canopy and six-cylinder engine is £873.