Putting a valuemi rating on equipment

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 66

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by John Dickson-Simpson

THE technical press is frequently asked to deal with quite fundamental questions about maintenance: "What size of workshop ought Ito have?" "What layout would you recommend?" "What equipment should I put in it?"

These questions are usually asked by people who are either starting in business or else want reassuring that they are on the right lines. They seem to expect accepted rule-of-thumb guidelines. But that would he just someone else's guess compared with their own. If you want something better than guesses you should be prepared to spend time reasoning out the economics. And that means trying to translate the pros and cons into cash terms.

Whether to have a workshop or not and what equipment is worth while are questions which in economic terms can be calculated on the basis of seeing whether the

investment is worth the time savings which result.

There are really two phases in an economic assessment of this sort. One is quite tangible. This is a matter of assessing the saving in time compared with doing the job another way and multiplying this by the current cost of labour. Or it can be a comparison with the cost of having repairs done outside. Supposing it costs £5000 to set up a small workshop, £500 for its annual running costs and at least £2000 for employing a mechanic, then you are probably looking for a fleet big enough to incur total maintenance costs — quite apart from the cost of spares — of about £3,500 a year before it is worth, in these terms, doing the maintenance yourself rather than putting it to outside repairers. Owner-drivers would not think in terms of counting a mechanic's salary into the economics but even in terms of cold value they need to be spending over £1000 a year on maintenance to be making a workshop an economic proposition.

Mind you, a small operator out in the country and able to fix up a cheap building might be able to set up a small shop for only about £2000. Obviously, that brings down the point of economic worth a good deal. It is the wide differences in circumstances which make it so misleading to try to apply blanket rules.

But one step is always sensible and that is to examine the typical labour rates which are charged by an outside garage for the maintenance of a vehicle each year. This means separating the labour cost from the spares costs. It is my guess that the maintenance labour cost is not going to be much more than £400 a year per vehicle even allowing for the odd major job.

In cold economic terms this seems to indicate that you need seven or eight vehicles in a fleet before it is worth setting up a workshop with a full-time mechanic; that it can be just about economic for an owner-driver doing his own maintenance if the outlay can be really slashed but that it does not look a completely sound proposition for a small do-it-yourself operator until two or three vehicles are in the fleet.

Beyond three vehicles the owner is unlikely to be able to spare the time both to drive and to do repairs. There can therefore be a period of poor return compared with fleet size when going through that painful phase building up from three vehicles to eight vehicles. But all this is looking at things in just cold economic terms. In transport the cold economics are not the only consideration. There is the convenience factor the ability to get things done quickly without being dependent on other people. Here only bitter experience shows how important that independence can be. If there are good outside repair services the convenience of doing your own repairs is not so valuable.

More often than not, though, the service has to be scheduled with other bookings, there is poor ability to deal immediately with ad hoc repairs, and neither service nor spares are there at night or weekends, just those times when small operators devote time to maintenance.

Then the convenience itself can be translated into economic terms on top of the cold economic facts. After all, missing a job means ,paying out standing costs. It means losing a day's revenue as well. So anything between £30 and £40 goes out of the window on a day when a vehicle is held out of service because there is delay in getting its maintenance done. If that happens once a month that is another £400 of yearly value which needs adding to the basic economic value, comparing just the costs with those of outside repairs.

Counting in the convenience factor puts the self-controlled workshop in a brighter light. It still might not make it worth an owner-driver having his own workshop; that depends on the investment and overheads surrounding his own circumstances and whether he wants to devote spare time to maintenance and, indeed, whether he thinks he has the skills. But counting in the convenience factor does make it much more likely that one's own workshop is worth while when there are two vehicles in the fleet.

How big?

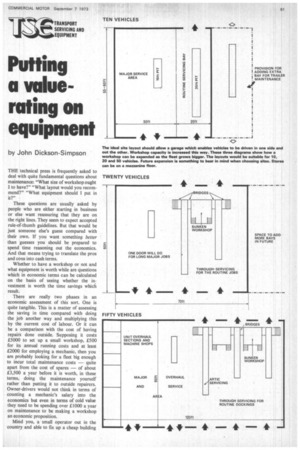

What size and layout of workshop? Well, clearly, the minimum size is one vehicle. Whether more space is required depends on whether a longer job such as annual-test preparation is likely to be going on at the same time as routine maintenance on another vehicle. That is unlikely until the fleet size reaches three or four vehicles. If a test preparation takes a week, the monthly inspection and servicing of another two or three vehicles can probably be fitted into the other three weeks.

In practice, it is even easier than that, and a workshop big enough to take two vehicles at once is rarely needed until there are more than six vehicles in the fleet. The workshop demands for a small fleet are, in fact, quite modest. It is surprising how efficient a Nissen hut with a pit can be.

To get a fairly accurate idea of what size of workshop is needed, you need to assess not just the fleet size but the age of the vehicles this affects the likelihood of repairs-incidence and the sort of work they are on. The work they do affects the frequency with which they are serviced and inspected.

Every vehicle has to be inspected and overhauled thoroughly every year now because of the governmental annual test. So that is one vehicle's space which is needed for every 50 vehicles, theoretically, if each vehicle takes a week to prepare for its test. That is assuming the test can be so beautifully phased weekby-week throughout the year; that is extremely unlikely. So let us say one space for test preparation for every 20 vehicles.

Then, even if you are lucky, every vehicle is likely to need some major repair. probably lasting about a fortnight, once in two years. Again, such dockings have a habit of not being very well regulated, so that you can get two such major repairs running consecutively, or even at the same time. Again, it probably boils down to needing another space for every 20 vehicles for major repairs.

The capacity of a bay for just the routine servicing and inspections can be estimated fairly accurately. Suppose there are 250 working days in a year and that each service or inspection takes half a day. That gives a capacity for 500 services in a year. Divide that by the number of services each vehicle is expected to need in the year and you can make a good stab at the fleet size with which that service bay can deal. lf, for example, the vehicles are working hard and need servicing every fortnight the service bay's capacity is probably about 20 vehicles; but if the vehicles are serviced just once a month then the capacity is doubled to 40 vehicles.

So it is possible to draw up some rough estimates comparing fleet size with workshop space, but the steps in fleet size with which different sizes of workshop can cope tend to be rather coarse. For example. although one overhaul bay plus one service bay can deal comfortably with 10 vehicles, it begins to struggle a bit when it has to deal with 20 vehicles. One service bay can deal with six vehicles comfortably but making the same bay handle 10 vehicles calls for some skill in organization. It is when the workshop is hard worked that the value of equipment is appreciated most. Again it is auite possible to make rational assessments of the time savings which different sorts or workshop equipment can produce compared with the annual cost of amortizing the price.

This is where the old controversy between pits and lifts comes in. A pit has several virtues, and even companies who like lifts often still have a pit as well. A pit is cheap. It can be covered temporarily so that no floor space is lost. It can be constructed on a do-it-yourself basis. There is virtually no limit on the weight of vehicle it can accommodate. Its capital cost can usually be recouped in a year through a probable 30 per cent time-saving compared with the alternative of crawling underneath a vehicle on your back.

Lifts are comparatively expensive. It takes two or three years to redeem their capital cost. Also, they take up permanent floor space. unless they are of the fully retracting hydraulic-post type. They need generous headroom as well. But work can often be done more efficiently with a lift. Plenty of natural light is available. They can be adjusted to any convenient height whereas the working level of a pit is fixed.

With external corner-post models no excavation is needed, and, if some time it were wished to alter the workshop layout, this could be done reasonably easily. Also, there are no problems of cleaning and draining as there are with pits — and no ventilation problems either.

A prime attraction of lifts is that mechanics work at floor level. Energy and time are not wasted clambering in and out of a pit every time a spare part is wanted or some bench work has to be done or a forgotten tool collected. Moreover, there is free walk-round access to most parts of the vehicle. All this enables more work to be done in a day with a lift than with a pit. So a lift is a good thing where workshop capacity is at full stretch or where quick servicing turnrounds are especially important.

Of course, where the size of a fleet justifies it. more elaborate pit arrangements can be installed which incorporate some of the advantages of lifts. Hydraulic trolley jacks can traverse the length of a pit to give extra lifting. A sunken workshop at pit-floor level can speed access to and from the workbench. Fabricated-steel walkways on piers give more natural light and more room to work than excavated pits.

For steam-cleaning and washing, pits are not suitable — and indeed give risk of asphyxiation if not plain unpleasantness. Either a lift or a ramp is needed for such major cleaning jobs. Ramps can be used for normal maintenance as well, of course. They are quite simple to construct and are cheap because they involve no excavation. But they do make a permanent claim on floor space.

The pros and cons of the various elevating systems need weighing up in the light of the cash available, the facilities, the sizes of vehicles and the degree of utilization. For example, an expensive lift can deal with more vehicle servicings in a day than almost any other method of below-deck working; but if only one vehicle is being serviced a day a lift is a luxury.

On the whole, decisions on buying maintenance equipment are still somewhat rule of thumb. Years of experience give a hard-headed transport man a surprisingly shrewd judgment on whether it is worth while investing in some new equipment. It does not strictly need a lot of figures to tell a manager whether he does enough painting in a year to justify a portable paint-spray plant, for example.

Not that figures represent the sole basis of judgment, anyway. It may be realized that a paint-spray plant is a luxury and the time-saving does not affect the cost; but if the additional cost is small enough it might still be worth spraying because it is easier to get a good finish.

When assessing what equipment is needed, a natural division will often be found between what is essential and what is a refinement. Without the essentials you cannot do any maintenance at all. With the refinements you can do the maintenance easier, better or quicker; how much easier, better or quicker — and the money saved as a result — indicates whether the investment would be wise.

New equipment Take a simple example. As you cannot undo nuts with your fingers, you need spanners. They are essential. But a powerdrive spanner is a refinement. Can the time it saves be devoted to other work and translated into money, represented in man hours? Similarly, a torque wrench is a refinement. Can the reduced risk of pulled-threads, stretched studs or cylinder-head gasket failures compensate for the extra cost?

When you scrutinize proposals for new equipment in economic terms like this, the cost of labour becomes the parameter. Not surprisingly there is more readiness these days to buy workshop equipment because of the difficulty in getting labour in the first place and the high cost of the labour in the second place. Obviously there is every incentive to make the best possible use of mechanics' time — and the incentive will get stronger over the years, not weaker.

The problem is no less diminished for the small operator and even the many owner-drivers. There will be more and more tendency to invest in "refinements" as the cost of outside repairs continues to escalate and less time off the road _ has to be reconciled with a higher standard of maintenance.

In applying economic scrutiny to the routine task of lubrication, for example, compare the cost of doing it yourself with the cost of having it done by an outside garage.

As it is best to apply grease under pressure, a portable pressure lubricator is worth buying. This will cost about £90. Spread over several years this is negligible. What is not so negligible is the cost of labour. In a small fleet this will probably be part of the driver's tasks, although when a fleet reaches a size of about six vehicles the lubrication can become a mechanic's responsibility.

After weighing up these costs and comparing them with the cost of having the job done outside, see whether it is cheaper doing it yourself, or, if not, whether the extra cost is small enough still to make it worth while doing the lubrication yourself, because of the convenience and more reliable supervision. Surprisingly enough, often the cheapest lubrication method for small fleets is actually to fit the vehicles with automatic lubrication.

Another man?

Just the same approach can be used for the purchasing of any equipment or the employment of extra staff. Will employing another man result in lower overall costs than giving the work he could do to an outside firm? Even if it is not cheaper, is it worth it in the convenience of being able to get on-the-spot attention and probably less time off the road? Remember, profit is lost and the standing costs go on all the time a vehicle is off the road. It probably loses at least £12 a day, not counting the driver's wages.

If considering buying some fresh equipment, try to estimate how much quicker a man can do the job as a result and translate this into the labour cost saved whenever the equipment is used. Multiply it by the hours of usage you expect of the equipment in a year (and this is directly related to fleet size), divide into the cost of the equipment (with tax allowances this may be eventually just over half the cash price) and you can see how many years the equipment will take to pay for itself.

The answer is not always in favour of buying the equipment, especially where a very good outside service exists. Some cases in point are fuel-injection, electrical and tyre services. On the whole, these are now so efficient that not many operators bother equipping their own workshops to deal with these items.

There is, in fact, a steadily growing tendency to replacement of units rather than repair of units as the manufacturers get their services better organized and cheaper in proportion to labour costs. For example, it is now almost always cheaper to buy a reconditioned Perkins, Bedford, Ford or Leyland engine rather than do a major overhaul yourself. Besides which, setting yourself up for engine overhauls costs about £700 these days, so it takes several overhauls to make the outlay worthwhile.

Nevertheless, when you run the expensive diesels, which now cost at least £450 for reconditioned units, it is often worth doing the job yourself. It usually amounts to only a partial overhaul — say, fresh valves, pistons and liners — after all.

So operators' workshops are relying more and more on equipment which falls into a loose "essential" category. But there is still a lot to choose from, as a flick through a factor's catalogue will show.