LITTLE DEMONS

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Mere novelties — or cost effective CVs? In either case microvans, are becoming common sights on British streets. We've been out and about with a brace of Daihatsus.

• " . . . the fitting of a van body on a light, pleasure-car chassis, even if the pneumatic tires (sic) are retained, is not likely to prove successful."

We doubt whether the manufacturers of car-derived vans would agree with the sentiments of Henry Sturmey, writing in The Commercial Motor of April 2, 1908. Nonetheless, 80 years on, the success of the purpose-built microvan in the field of light delivery world would seem to add weight to his opinions.

Today many pundits write off the microvan merely as a clever piece of marketing, seeking to find buyers between the car-derived van, and the light panel van sectors. Others regard the little vans as viable commercial vehicles, tailored to the needs of the small business user.

Either way, Henry Sturmey would probably stick to his guns and re-assert "that irrespective of whether the load to be carried is 5cwt or 5 tons, or whether it is required to do cab work, or carry travellers, cars for commercial work must be designed from 'A' to 'Z' for the work they have to do," Fifteen Love to the microvans.

They have, of course become a common sight on our roads in the last few years, and the body options now available include reefers, demountable caravans — even hydraulic lifts for streetlamp inspection work.

Bedford and Suzuki are at the forefront of microvan manufacturers by virtue of their UK manufacturing base for the Rascal and the Super Carry respectively. Unhampered by quota restrictions, they have gained wide acceptance for the microvan in the UK. By contrast, quota-throttled Daihatsu and the other Japanese importers have had to segment the microvan market into even smaller chunks to ensure the success of their products. Subaru already offers a four-wheel-drive version of its 700 microvan, but no 4WD micro pickups have been available — until now.

The Daihatsu 850 microvan has been on the UK market for five years and its replacement, the rebodied Hijet, was introduced in low-roof form at the Motor Show last September. The company had toyed with the idea of importing a 4WD version of the 850 van at the end of 1984, but the success of the Fourtrak range used up the available space on its quota.

It was at the Royal Smithfield Show last December that Daihatsu made the surprise announcement that it intended to bring in the 4WD micro pickup which, with the Hijet 4x2 van, now comprises the company's UK microvan range.

• BODYWORK

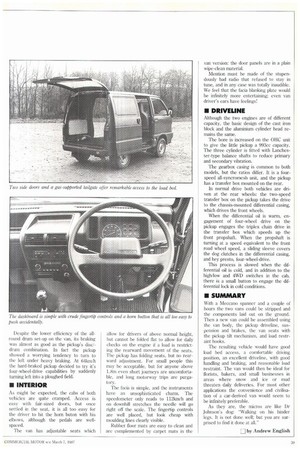

The Hijet has been revamped into an attractive little vehicle. The compact look of its sloping aerodynamic nose and low roof belies its 2.9m3 load volume. Twin sliding side doors and a tailgate make access to the load bed simplicity itself. After all, the van is so small that one can reach across from one side door to the other!

The load bed is 540mm high and car

peted, although there are no load restraining devices mounted in the van, and loads tend to slide about as a result. All the doors have interior locking buttons, but only the gas-strut-suspended tailgate and the driver's door have exterior locks. This poses no problem as the side and passenger doors can easily be reached for unlocking from the driver's seat.

The pickup has a slightly higher load bed at 665mm and tough-looking drop sides with neat catches. Roping hooks adorn the sides, and the side-mounted battery completes the effect of a large truck after a crash diet.

Both micros share the same sturdy boxsection chassis, which carries the driveline and the suspension. The integral bodies, however, with the exception of the pickup's dropsides, are of quite thin construction, and rust may be a long term problem despite good quality coachwork.

• PERFORMANCE

"There's no substitute for cubes," as the saying goes, and this becomes immediately apparent upon driving either vehicle. The engines seem to be rather inflexible, and revs have to be kept up to make good progress. The gear ratios accentuate this, particularly the wide gap between third and fourth.

With its lower-powered engine the loaded van will maintain 112km/h on the motorway, but only with some teethgrinding acceleration. The pickup has 150cc more engine capacity than the van, and this makes all the difference as the engine has enough power to pull it through the doldrums of fourth gear to make driving a more pleasant experience.

The laden acceleration figures tell the rest of the tale. While the pickup is a gutsy little beast, the van is simply underpowered.

The transfer box whine on the pickup is clearly audible at speeds below 96km/h, but above that the two micros are equally noisy. Voices need to raised at 11210n/h and long journeys are tiring.

• FUEL CONSUMPTION

The pickup's better performance is paid for in its fuel consumption figures. Neither vehicle is particularly economical compared with the car-derived van opposition, although considering the urban habitat of most microvans this may not deter too many of its potential owners.

The pickup could only achieve a laden figure of 9.8fitilOOkm (28.8mpg), compared with the van's 8.811t/1 00km (32.2mpg). We have no figures for the pickup's fuel consumption when in fourwheel-drive but presume it would suffer.

• SUSPENSION AND HANDLING

Short vehicles like a microvan with the engine and the load mounted close to the centre of gravity have a low polar moment of inertia. This means that the vehicle (depending on spring rates) will be more responsive to changes in direction, and nippier around town — but it will also suffer from suspension pitch, and will tend to be less stable at high speed when travelling in a straight line.

Inherent problems like this can be designed out using the correct spring rates, but the very nature of the microvan means that suspension travel,. and therefore possible modifications, are very restricted.

On the whole the compromise reached with the pickup is fairly acceptable. The higher spring rates mean that the vehicle's handling is a good balance between laden and unladen onand off-road conditions. This does mean that the wheels are prone to sliding on occasion, but the ride is not harsh.

The pick-up could never be accurately described as an off-road vehicle — its ground clearance is too low for that — but its front suspension has been considerably beefed up for that occasional trip across a ploughed field.

The cross-member, dampers, springs, lower arms and ball ;oints have all received attention, which is just as well, for the front receives a considerable pounding, even on badly rutted roads. The road tyres are the final limiting factor; on slippery surfaces the vehicle will come to a sliding stop with all four wheels turning. Rib-and-lug tyres are available as a standard fitment from dealers; with them the little pickup should be able to cope with any hazards it is likely to encounter on a delivery round.

After a drive in the pickup, the van comes as a complete surprise. It wallows around corners on its soft suspension even when the tyres are inflated to 0.7 bar (10psi) above their normal loaded pressures.

Unladen at motorway speeds the van is pushed about like a feather by the wash from trucks; loading the vehicle improves this situation only marginally. It is hard to believe that the two vehicles are based on the same Macpherson strut-type suspension design, given the chasm that divides them.

• BRAKING

The pitching problems of the microvans comes to a head when braking hard at low speeds. At 32 to 48km/h the vehicle's front suspension compresses to the bump-stops, rebounds, and is compressed again. A weird oscillating movement is the result, which is most disconcerting. At speeds above 48knilli the suspension stays on the bump stops at the limit of its travel because of the higher G forces, and the braking process becomes altogether more confident. Despite the lower efficiency of the allround drum set-up on the van, its braking was almost as good as the pickup's discidrum combination. In fact the pickup showed a worrying tendency to turn to the left under heavy braking. At 64krnih the hard-braked pickup decided to try it's four-wheel-drive capabilities by suddenly turning left into a ploughed field.

• INTERIOR

As might be expected, the cabs of both vehicles are quite cramped. Access is easy with fair-sized doors, but once settled in the seat, it is all too easy for the driver to hit the horn buton with his elbows, although the pedals are wellspaced.

The van has adjustable seats which allow for drivers of above normal height, but cannot be folded flat to allow for daily checks on the engine if a load is restricting the rearward movement of the seats. The pickup has folding seats, but no rearward adjustment. For small people this may be acceptable, but for anyone above 1.8m even short journeys are uncomfortable, and long motorway trips are purgatory.

The facia is simple, and the instruments have an unsophisticated charm. The speedometer only reads to 112krn/h and on downhill stretches the needle will go right off the scale. The fingertip controls are well placed, but look cheap with moulding lines clearly visible.

Rubber floor mats are easy to clean and are complemented by carpet mats in the van version: the door panels are in a plain wipe-clean material.

Mention must be made of the stupendously bad radio that refused to stay in tune, and in any case was totally inaudible. We feel that the facia blanking plate would be infinitely more entertaining; even van driver's ears have feelings!

DRIVELINE

Although the two engines are of different capacity, the basic design of the cast iron block and the aluminium cylinder head remains the same.

The bore is increased on the OHC unit to give the little pickup a 993cc capacity. The three cylinder is fitted with Lanchester-type balance shafts to reduce primary and secondary vibration.

The gearbox casing is common to both models, but the ratios differ. It is a fourspeed all-syncromesh unit, and the pickup has a transfer box mounted on the rear.

In normal drive both vehicles are driven at the rear wheels: the two-speed transfer box on the pickup takes the drive to the chassis-mounted 'differential casing, which drives the front wheels.

When the differential oil is warm, engagement of four-wheel drive on the pickup engages the triplex chain drive in the transfer box which speeds up the front propshaft. When the propshaft is turning at a speed equivalent to the front road wheel speed, a sliding sleeve covers the dog clutches in the differential casing, and hey presto, four-wheel-drive.

This process is slowed when the differential oil is cold, and in addition to the high/low and 4WD switches in the cab, there is a small button to engage the differential lock in cold conditions.

• SUMMARY

With a Meccano spanner and a couple of hours the two vans could be stripped and the components laid out on the ground. Then a new van could be assembled using the van body, the pickup driveline, suspension and brakes, the van seats with the pickup tilt mechanism, and load restraint hooks.

The resulting vehicle would have good load bed access, a comfortable driving position, an excellent driveline, with good handling and braking, and reasonable load restraint. The van would then be ideal for florists, bakers, and small businesses in areas where snow and ice or mud threaten daily deliveries. For most other applications the convenience and civilisation of a car-derived van would seem to be infinitely preferable.

As they are, the micros are like Dr Johnson's dog: "Walking on his hinder legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all."

[j] by Andrew English