A Case of Understatement

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

How Ignorance of the Elements of Costing Caused an Operator to Accept a Contract for the Use of a 20-seater Coach at a Figure that Showed a Big WM

GOODS hauliers often land in trouble with their customers when they are asked to carry loads well below the capacity of the vehicle employed and charge the customer the rate applicable to the size of lorry. The haulier is perfectly justified as the cost of operating a vehicle and the rate to be charged are unaffected by the light loading. If, for example, an operator be pressed by a customer to carry a 10-cwt. load for a 50-mile run and the journey has to be made by a 3-tonner, then, assuming he has no opportunity either of making up the load or obtaining a return load, he must charge the rate for a 3-tonner running 100 miles.

The coach operator has similar problems. He is often asked to take on contracts which involve small weekly mileages under conditions which prevent him from using the coach for any other purpose during the week. In such cases the logical way of assessing the charge is to calculate the actual cost of letting the vehicle, on a time-and-mileage basis, adding a percentage for profit, but when the customer is presented with the bill, so calculated, he is apt to be as surprised and aggrieved as the customer of the goods haulier.

There are cases in which the coach operator takes on a contract without going closely enough into the details of the job, only to find, when he sends in his bill, that there is a rate for the contract fixed by some authority and that he is expected to operate at a loss. Sometimes, what is worse, when he tries to make out a statement of income and expenditure in support of an appeal for better treatment, he fails because his statement of expenditure is incomplete, so that he appears, according to his own figures, to be in a better position than he really is.

Transport for Workmen An example of this kind of occurrence was brought to me recently by an inquirer, and, as it is typical, it is worthy of discussion. The matter arose in connection with the building of a new housing estate. The contract was for the conveyance of workmen from town A to the site at B. The distance was 21 miles, and the coach, a 20-seater, was required to carry a full load of workmen to B each morning and to bring them back to A at night.

The coach proprietor's premises are at C, which is 12 miles from A, ard he decided to garage the coach at A during the week, arranging that the driver also should lodge in that town, coming home for the week-end. This procedure involved him in some extra expense: 35s. per week for the driver's lodgings and 7s. 6d. per week to garage the coach. These amounts had to be paid weekly by the man.

Apparently, about the time that he undertook the contract, there was a meeting amongst the local coach proprietors and certain officials, when agreement was reached on rates. This operator was unable to be present, but he was subsequently informed that the agreement was that the payment for a 20-seater coach was to be Is. per mile, plus an allowance for standing idle, which worked out, in his case, to £1 per day.

A Faulty Assumption

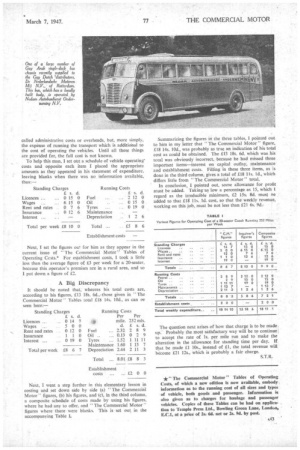

In the beginning this man, in his innocence, took it for granted that these rates, agreed collectively by his fellows in the industry and high officials of the Ministry of Transport, were likely to be fair and reasonable. After a month or so, however, some initinct warned him that all was not well, and he wrote to me. In his letter be enclosed two statements, one of expenditure and the other of receipts. They were as follows:—

His comment on the amount of the balance was that 'it gives very little margin for maintenance." Had he been near enough to me, I think that I would have given him a good dressing down! Obviously, this man does not know the A B C of costing. It is so simple and yet few know it.

It amounts to the fact that there are 10 items of cost, five standing charges and five running costs. If, in any statement of expenditure, such as that sent to me by the operator and given here, there are fewer than 10 items, the costs are incomplete and, therefore, useless as a means for computing profit and loss. After these costs come establishment costs. sometimes

called administrative costs or overheads, but, more simply, the expense of running the transport which is additidnal to the cost of operating the vehicles. Until all these things are provided for, the full cost is not known.

To help this man. I set out a schedule of vehicle operating' costs and opposite each item I placed the appropriate amounts as they appeared in his statement of expenditure. leaving blanks when there was no information available. thus:—

Standing Charges Running Costs £ s. d. s. d.

Licences ... ... 0 15 0 Fuel 2 12 (1 Wages . 615 0 Oil 0 15 0 Rent and rates 0 7 6 Tyres ... 0 19 0 Insurance 0 12 6 Maintenance Interest Depreciation 1 2 6 Next, I set the figures out for him as they appear in the current issue of "The Commercial Motor " Tables of Operating Ccsts.* For establishment costs, I took a little less than the average figure of £3 per week for a 20-seater, because this operator's premises are in a rural area, and so I put down a figure of £2.

A Big Discrepancy It should be noted that, whereas his total costs are. according to his figures, £13 18s. 6d..those given in "The Commercial Motor Tables total £18 14s. 10d.. as can oe seen here:—

Next, I went a step further in this elementary lesson in costing and set down side by side (a) "The Commercial Motor' figures, (b) his figares, and (c), in the third column, a composite schedule of costs made by using his figures, where he had any to offer. and "The Commercial Motor '' figures where there were blanks. This is set out in the accompanying Table I. Summarizing the figures in the three tables, 1 pointed out to him in my letter that "The Commercial Motor" figure. £18 14s. 10d., was probably as true an indication of his total cost as could be obtained. The £13 18s. 6d. which was his total was obviously incorrect, because he had missed three important items—interest on capital outlay, maintenance and establishment costs. Filling in these three items, as is done in the third column, gives a total of £18 us. id., which differs little from "The Commercial Motor" total.

In conclusion, I pointed out, some allowance for profit must be added. Taking.as low a percentage as 15, which I regard as the irreducible minimum. £2 15s. 8d. must oe added to that £1/1 lls. Id. cost. so that the weekly revenue, working on this job, must be not less than £21 6s. 9d.1 The question next arises of how that charge is to be made up. Probably the most satisfactory way will be to continue, to accept the rate of Is. per mile run and to make the alteration in the allowance for standing time per day. If that be made 11 10s., instead of £1, the total revenue will become £21 12s., which is probably a fair charge.

S.T. R.