ON SAFE GROUND

Page 32

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Stron. .erformance excellent brakes a useful .a load and a com•etitive .rice should make the L300 a stron. contender.

But it is not et read to take on the •anel van class leaders.

• Why do the Japanese favour forwardcontrol vans? Is it because they have all chosen the Volkswagen Transporter as a successful European role model? Or have they identified a new phenomenon; the van driving wanna-be? In this case, wannabe truckers, and since most trucks are forward control, maybe they think that producing scaled-down versions will keep van-man happy until he can take his HGV test and join the big boys.

There may be other reasons, of course, like shorter overall length for a given load space, or the specific operational requirements of the Japanese market. In any case, few Europeans except for VW and Bedford (with the Japanese-designed Midi) share the Japanese enthusiasm for the 'bums-over-wheels' format, and it was generally abandoned years ago.

The question of safety in a frontal impact has been discussed in Commercial Motor before, but it may be that the addition of massive front bumpers and Yshaped chassis sections on Japanese forward-control vans indicate that they were not originally aware of all aspects of the VW design.

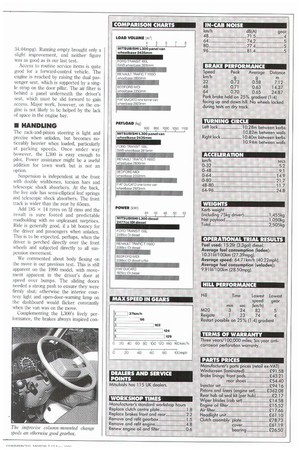

The Mitsubishi L300 LWB panel van fits neatly into the Japanese mould. We last tested a diesel version over three years ago (CM 21 February 1987) and were interested to see what changes have been made. The price has risen, of course. The 19.5% increase works out at 6.5% per year, to V8,959 ex-VAT. This is still competitive with the L300's rivals, falling between the Renault Trafic 11000 (£8,535) and the Bedford Midi (£9,188) in our competitors' list.

• BODYWORK

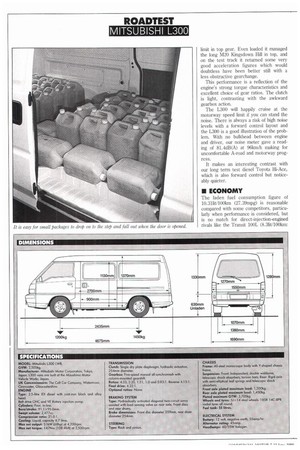

Access to the load area is very good, thanks to a large sliding door each side and a high lifting tailgate. At 5.67m3, the load volume is quite respectable, but no match for the ,Sevel built Fiat Ducato's excellent 6.44nri. The 1,050kg payload is, however, near the top of the class in our comparison chart.

There are no load restraining points in the L300 and this allows cargo to fall onto the step by the sliding doors. A bulkhead runs the full width of the van behind the engine which, combined with a bar at the tap of the seat backs, should prevent the load from interfering with the driver or passengers. This bulkhead has a small central bulge to accommodate the gearbox which intrudes slightly into the load space.

• DRIVELINE

The indirect-injection 2.5-litre diesel engine can be found in the L200 pickup and, in turbocharged form, in the Shogun. Producing 51kW (68hp) at 4,200rpm and 147Nm (108.4lbft) at 2,500rpm in naturally aspirated form, it has no difficulty in propelling the L300.

Drive is transmitted to the rear wheels through a five-speed gearbox with a column-mounted gearshift. Maybe this gives more cabin space for a third passenger, but the pay-off in gearchainge quality is too great. We criticised this set-up in our last test and nothing seems to have been done to improve it. The linkages between gearbox and lever lead to a slow and imprecise change, and fifth gear is hard to engage until the gearbox oil has warmed. This might have been acceptable 30 years ago, but not now. The gate itself is well defined, but the change really does need major improvement.

• PERFORMANCE

On our unladen test run, the L300 cruised up both our timed hillclimbs at the legal limit in top gear. Even loaded it managed the long M20 Kingsdown Hill in top, and on the test track it returned some very good acceleration figures which would doubtless have been better still with a less obstructive gearchange.

This performance is a reflection of the engine's strong torque characteristics and excellent choice of gear ratios. The clutch is light, contrasting with the awkward gearbox action.

The L300 will happily cruise at the motorway speed limit if you can stand the noise. There is always a risk of high noise levels with a forward control layout and the L300 is a good illustration of the problem. With no bulkhead between engine and driver, our noise meter gave a reading of 81.4dB(A) at 96km/h making for uncomfortable A-road and motorway progress.

It makes an interesting contrast with our long term test diesel Toyota Hi-Ace, which is also forward control but noticeably quieter.

• ECONOMY

The laden fuel consumption figure of 10.31lit/100km (27.39mpg) is reasonable compared with some competitors, particularly when performance is considered, but is no match for direct-injection-engined rivals like the Transit 100L (8.31it/1001an:

34.04mpg). Running empty brought only a slight improvement, and neither figure was as good as in our last test.

Access to routine service items is quite good for a forward-control vehicle. The engine is reached by raising the dual passenger seat, which is supported by a single strap on the door pillar. The air filter is behind a panel underneath the driver's seat, which must be slid forward to gain access. Major work, however, on the engine is not likely to be helped by the lack of space in the engine bay.

• HANDLING

The rack-and-pinion steering is light and precise when unladen, but becomes noticeably heavier when loaded, particularly at parking speeds. Once under way however, the L300 is easy enough to pilot. Power assistance might be a useful addition for town work but is not an option.

Suspension is independent at the front with double wishbones, torsion bars and telescopic shock absorbers. At the back, the live axle has semi-elliptical leaf springs and telescopic shock absorbers. The front track is wider than the rear by 65riarn.

Add 185 x 14 tyres on 5J rims and the result is sure footed and predictable roadholding with no unpleasant surprises. Ride is generally good, if a bit bouncy for the driver and passengers when unladen. This is to be expected, perhaps, when the driver is perched directly over the front wheels and subjected directly to all suspension movement.

We commented about body flexing on the move in our previous test. This is still apparent on the 1990 model, with movement apparent in the driver's door at speed over bumps. The sliding doors needed a strong push to ensure they were firmly shut; otherwise the interior courtesy light and open-door-warning lamp on the dashboard would flicker constantly when the van was on the move.

Complementing the 1.300's lively performance, the brakes always inspired con fidence. With powerful servo assistance, the front discs and rear drums stopped the van without fuss or drama in our braking tests. There was never a hint of locking wheels and the Mitsubishi always pulled up in a straight line.

The handbrake is a 'proper pull-up type between the front seats and is easily reached — a refreshing change from the umbrella type fitted to many Japanese light commercials. It held the L300 with ease on the 25% (1:4) hill used for our restart test. In the press release we received with the vehicle, Mitsubishi stresses the importance of aerodynamics in designing the L300, boasting its Cd figure of 0.47. That might be so when the vehicle is travelling forwards, but it was badly affected by sidewinds. Whether it was cross winds or passing vehicles on the motorway, steering correction was constantly required to keep the van on a straight course. This never caused alarm but was worse than on some other, larger vehicles we have tested.

• INTERIOR

Perched on the front wheel arches, the driver has a good all-round view of the road, helped by the deep windscreen and large door mirrors. The driver's seat has a good range of fore-and-aft adjustment and the seat back can be reclined, so most drivers should find a comfortable position. Headroom is acceptable but shoulder room is restricted, indicating that the third passenger seat is at the expense of space for the driver.

Stowage space is not particularly generous, with a fair-sized glovebox and an elasticated pocket on the driver's door. The interior is trimmed in grey with a padded headlining running the full length of the van. Rubber mats cover the cab floor which should be easy to clean or hose out if necessary.

All dashboard controls are illuminated when the lights are switched on; the only minor irritaton is the fuel cap release, which is buried behind the handbrake between the seats.

All instruments are clear and simple. A Above: The fuel-filler release is buried behind the handbrake inside the cab. Below: Routine items are easily reached, but major work could be more difficult. central semi-circular speedometer is flanked by a fuel gauge to the left and temperature gauge to the right. The fascia surrounding the instruments and controls is black, which breaks up the monotony of the grey trim. A stereo radio-cassette is fitted but the high noise level makes it of limited use at speed.

• SUMMARY

The long-wheelbase L300 has a lot to offer. It is well finished, with easy access to the load area, good performance and brakes. For use over short distances, it would be tolerable.

Some of its problems, particularly noise, are related to its forward control layout, but that column-gearchange should be junked, even if it is at the expense of the centre seat. In short, it does most things well; but it is not going to give anyone at Ford too many sleepless nights. LJ by John Kendall

In today's complex and demanding distribution sector, a truck that claims to meet everybody's needs at 17 tonnes will fall short in many critical areas.

Which is why Leyland DAF offer you a choice of vehicles to perfectly meet your individual requirements.

The 17.16 is particularly suitable for local multi-drop operations; the 17.18 with its higher output and axle loading tolerances represents the backbone of the range, whilst the FA 1900 DNS remains a premium performer over those longer distances.

The various options available within the range ensure a vehicle to meet every need.

So, with such diversity at 17 tonnes, you'll be pleased to know we don't just make one.