PEOPLE 1st MACHINES 2nd

Page 26

Page 27

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The engineers put the human factor before consideration of 40 tonnes, spray and errant wheels, and were told to learn to use both sides of their brains

• The Institute of Road Transport Engineers has recognised that it is the man, not the machines, that matter most. Largely ignoring the obvious attractions of 40 tonnes, spray suppression and errant wheels, the IRTE's annual conference at Solihull examined the human factor with the immodest theme: "Expertise, the Transport Engineer at Work."

According to conference link-man, television presenter and "professional communicator" William Woo!lard: "Greater expertise is the catch-phrase for the Eighties and Nineties. Flying by the seat of your pants is out, professionalism is in."

With a large and interesting display right outside the conference hall, the speakers had to earn the delegates' dedicated attendance; the engineers were not afraid to vote with their feet if the draw of the drawbars outside proved too strong.

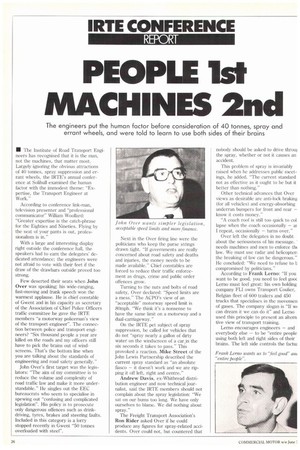

Few deserted their seats when John Over was speaking; his wide-ranging, fast-moving and frank speech won the warmest applause. He is chief constable of Gwent and in his capacity as secretary of the Association of Chief Police Officers traffic committee he gave the IRTE members "a motorway policeman's view of the transport engineer". The connection between police and transport engineers? "Six thousand people a year are killed on the roads and my officers still have to pick the brains out of windscreens. That's the bottom line when you are talking about the standards of engineering and road safety generally."

John Over's first target was the legislators: "The aim of my committee is to reduce the volume and complexity of road traffic law and make it more understandable." He singles out the EEC bureaucrats who seem to specialise in spewing out "confusing and complicated legislation". His policy is to prosecute only dangerous offences such as drinkdriving, tyres, brakes and steering faults. Included in this category is a lorry stopped recently in Gwent "50 tonnes overloaded with steel". Next in the Over firing line were the politicians who keep the purse strings drawn tight. "If governments are really concerned about road safety and deaths and injuries, the money needs to be made available." Chief constables are forced to reduce their traffic enforcement as drugs, crime and public order offences grow.

Turning to the nuts and bolts of road safety, Over declared: "Speed limits are a mess." The ACPO's view of an "acceptable" motorway speed limit is 80mph. "We think it's a nonsense to have the same limit on a motorway and a dual-carriageway."

On the IRTE pet subject of spray suppression, he called for vehicles that do not "spray nearly a gallon of dirty water on the windscreen of a car in the six seconds it takes to pass." This provoked a reaction. Mike Street of the John Lewis Partnership described the current spray standard as "an absolute fiasco — it doesn't work and we are ripping it off left, right and centre."

Andrew Davis, ex-Whitbread distribution engineer and now technical journalist, said the IRTE members should not complain about the spray legislation: "We sat on our bums too long. We have only ourselves to blame. We did nothing about spray."

The Freight Transport Association's Ron Rider asked Over if he could produce any figures for spray-related accidents. Over could not, but countered that

nobody should be asked to drive throw the spray, whether or not it causes an accident.

This problem of spray is invariably raised when he addresses public meetings, he added. "The current standard not as effective as it ought to be but it better than nothing."

Other technical advances that Over views as desirable are anti-lock braking (for all vehicles) and energy-absorbing widerrun bumpers for front and rear — know it costs money."

"A coach roof is still too quick to col lapse when the coach occasionally — at I repeat, occasionally — turns over."

Over left the delegates in no doubt about the seriousness of his message. ' needs machines and men to enforce th( law. We must use radar and helicopter: the breaking of law can be dangerous." He concluded: "We need to refuse to b compromised by politicians."

According to Frank Lerno: "If you want to be good, you need to feel gooc Lerno must feel great: his own holding company FL! owns Transport Coulier, Belgian fleet of 600 trailers and 450 trucks that specialises in the movemen of gases. The company slogan is "If w( can dream it we can do it" and Lerno used this principle to present an ahem, tive view of transport training.

Lerno encourages engineers — and everybody else — to be "entire people using both left and right sides of their brains. The left side controls the factw

entitle thoughts while the right side -tains to feelings such as art, politics religion. "Einstein", explains Lemo, >ed left and right sides of his brain." "...ern° was scheduled to address the 4ineering problems of cross-border

• ss-Channel haulage traffic. He de:es that liberalisation for traffic within EEC is a must — "but not without monisation. Otherwise it will be a aster."

In Belgium, the maximum permitted iss weight is now 44 tonnes whereas ,sr. other EEC countries go to 40 Ines on July 1. Lerno says that a cumin weight limit throughout Europe is ;ential. He does not gain from 44 Ines GCW domestic operation because vehicles weigh one tonne more than urpose-built 40-tonner and so they re a payload deficit on international rk.

emo believes that European co-ordiion is difficult because "every country aks it knows best." He sees an import role for the IRTE and the European insport Maintenance Council to come and lobby in the interests of the inury. "We must be ingenious engineers make the European transport dream ne true," David ivison has been chief executive the IRTE for less than a year, but has ..ady concluded that the future of training good professional engims is hampered "because engineering tot seen as an attractive profession by st young people today. They want to e the soft option, the clean-handed :ion." He backs up this assertion with ires. One company in seven is likely be held back by skill shortages this Ir. Around 70 per cent of managers in tish industry get no training at all durtheir career.

[RTE council member Frank Austin d there is little incentive for people to ..:orne engineers because they rarely ke it to the top jobs — accountants and rations people usually become general nagers.

lvison's reply contained an element of ticism of his members: "Many trans

engineers I have met have not had 'ficient financial awareness of their eneering decisions. They will never rise the top of their industry unless they ie that financial awareness."

Unlike the Road Haulage Association, IRTE has praise for the Road Trans port Industry Training Board, even though the RTITB does not train senior transport engineers. lvison reports that this year there is a 25 per cent increase in the number of students studying for the IRTE exams.

Roger Denniss of Bass UK and a past chairman of the European Transport tenance Council had been asked to research the existence of the equivalent of the IRTE in other European countries. He reported that there is none; the IRTE is unique in Europe. He therefore proposed the establishment of a European IRTE centre in Antwerp to "develop IRTE international interest and broaden the Institute's vision in almost every area."

Denniss also claims that it would give the required professional recognition and "by a quantum leap improve road transport efficiency, safety and reduction in operating costs.

"It will provide Europe with a voice of practical experience which will prevent nonsensical vehicle legislation being made and adopted (if not always implemented) in all European countries."

lithe British Telecom fleet of vehicles was parked nose to tail, the resulting yellow traffic jam would stretch from Solihull to Newcastle or one and a half times round the M25. Andy Hayward, British Telecom's London region transport manager, revealed BT's approach to fleet engineering, bearing in mind that it regards transport "as coincidental to its mainstream activities and thus an expensive overhead".

In 1984 BT set up a Motor Transport Executive to run as a specialist organisation and operated as an in-house contract hire company. 'Ile internal divisions of WI' are charged by the Motor Transport Executive for the provision and servicing of the vehicles.

The 55,000 cars and commercials are maintained in 330 workshops, some of which specialise only in cars, commercials or mechanical aids. Claims Hayward: . . . with few exceptions the facilities enjoyed by BT mechanics are of a very high standard . . ."

"Multi-skill*" with mechanics trained in a variety of disciplines is BT's method of obtaining a flexible and productive workshop staff. It has its own transport technical training school at Stone in Staffordshire to teach the necessary skills. Since multi-skilling was adopted there have been tangible productivity improvements; the fleet is bigger but there are fewer workshop staff.

Standard vehicles are purchased wherever possible and there is heavy reliance on a computer system to measure vehicle performance and maintenance costs, parts usage and time allocation. Such systems. says Hayward, are now virtually compulsory for any medium to large organisation.

When it comes to recruiting transport engineers, Hayward says that he finds that too many academically qualified engineering graduates lack practical ability and applicability.

While Hayward describes transport engineers as part of a "skilled and noble industry", he believes that the public at large view them as "brawny, grimy, unsophisticated and obstructive".

The latest technical developments, he says, must be backed up by training: "Adequate technical training seldom precedes the introduction of systems employing new technology yet it is left to the transport engineer to ensure that he and his mechanics are prepared to deal with failures."

Microprocessor-controlled vehicle electronics are a good example of this: "Technical colleges should by now be introducing subjects like vehicle electronics into the motor vehicle curriculum."

Aside from the challenge of new technology, transport engineers also have to cope with what Hayward views as "changes in legislation which seem to do little more than mollify public reaction at considerable expense to our industry. And how will engineers cope with a lower cetane number for derv? At a time when the environmentalists are becoming so organised against road transport, obtaining and renewing the 0-licence is clearly becoming more difficult, yet the fuel companies seem hell-bent on creating yet more causes for objection by increasing white smoke emission on start-up and increasing engine noise."

This is where the IRTE comes in, says Hayward: ". . . the institute must continue to carry the banner for the morale and status of the transport engineer, who is going to be facing an increasingly more hostile operating environment in the years to come. "[7 by David Wilcox