IT'S extremely difficult to turn one's thoughts to snow and

Page 72

Page 73

Page 74

Page 78

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

ice and other winter driving hazards in mid-summer. Possibly this is why we are frequently caught unprepared when the winter weather arrives. No matter how late we get the first snow fall, some local authority cries out: "We weren't prepared for it."

After a snowfall there are demands from all quarters for an explanation of the resultant chaos; this happened in 1967 and 1968. No doubt the pattern will be repeated during the ensuing winter. Now that summer is here, who wants to think about the problem of snow clearing?

One section of the community who should be thinking about it are the paid officials and elected members of local authorities, many of whom are gathering this week at Brighton for the Public Cleansing Conference. Perhaps their thoughts will turn to these winter problems.

But why are we unprepared for winter conditions each year? At about this time councils are considering expenditure for next year. Officials have compiled budgets to meet the efficient working of their departments for the year. These figures include expenditure for equipment, men, and methods for snow clearing.

When considering a budget councillors must protect the interest of the ratepayers, and examine the proposed expenditure. Too often this means financial cuts in what seem at the moment to be the least important items. And in June what could appear less

important than snow clearing? After all, many councillors are "new boys" who have made election promises to reduce waste, or old boys who have just been re-elected after making similar promises. It's a precarious business being an official or a councillor, be it at city or county hall. If you spend the money on equipment which is not required you are the electorate's Aunt Sally—and so you are if you don't spend on equipment which is needed.

Not all authorities are without a plan of campaign or equipment, but many who believe themselves to be prepared are using antiquated equipment and outdated methods.

This is my criticism: my answer is a scheme which I consider adequate to meet the emergency requirements of a severe winter and which can be operated without too great a financial burden on the community.

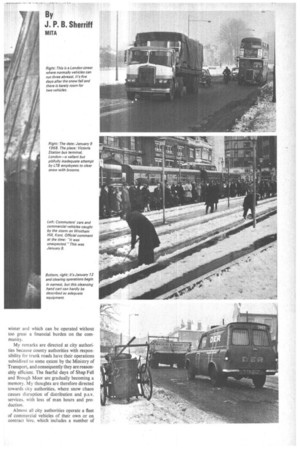

My remarks are directed at city authorities because county authorities with responsibility for trunk roads have their operations subsidized to some extent by the Ministry of Transport, and consequently they are reasonably efficient. The fearful days of Shap Fell and Brough Moor are gradually becoming a memory. My thoughts are therefore directed towards city authorities, where snow chaos causes disruption of distribution and p.s.v. services, with loss of man hours and production.

Almost all city authorities operate a fleet of commercial vehicles of their own or on contract hire, which includes a number of tippers. These fleets are divided among the various departments of the city for operational purposes. They are not always available for use by other departments until an emergency occurs—in many cases not even then. But for proper pre-planning of a winter maintenance programme these vehicles must be operated by one department.

Once this has been established the responsible official can plan without interference or hindrance from his colleagues, although he may require manpower from other departments which are unable to function because of the weather conditions.

Control point essential

To ensure early attention to snow and ice during darkness it is essential to have a control point manned by a responsible supervisor. The only equipment required is a telephone in each of two homes and a stand-by rota on an alternating basis.

The increasing mobility and system of communications common to most police forces through divisional cars or panda patrols should be recruited—if possible—to ensure early warning. Who is in a better position than a police driver to judge whether road conditions require attention? However, police are not obliged to do this and where they do not agree the stand-by driver must become the patrolman.

In either event it is essential that the emergency system goes into action as soon as the need arises: one half-hour delay proves disastrous. The first task is to muster the vehicle crews allocated on the basis of two for each vehicle. These men must be readily available, so they should be paid a retainer to stand-by in their own homes. At the least they should be easily located and available for work.

So much for the men—now what of the machines? Some authorities favour specially built gritting bodies mounted on old cleansing wagon chassis. If a chassis can no longer be used on a slow-moving, small mileage, refuse collection operation it is unlikely to be very dependable in a snow or ice emergency. If you opt for a gritting body then it is wise to use a dependable chassis.

These specially constructed bodies need not be permanently mounted as they are available on stilts and can be used on platform lorries or with dropside tippers. This method of operation is efficient but requires a degree of pre-planning for efficiency which may prove too costly for many councils. This type of equipment requires only one man who both drives and operates the spreader. It is particularly useful in rural areas.

The other type of equipment in common use is a gritting spreader fitted forward of the nearside wheels of the vehicle and requires a driver and an operator. This equipment operates when its drive wheel is engaged to the crown of the road-wheel tyre. It is necessary to cut a trap door in the floor of the vehicle to ensure a constant supply of material to the spreader.

Out-dated methods

I have purposely referred to the equipment in both cases as spreaders. The term gritter, which has been in general use for many years, indicates the out-dated methods of many authorities. In the days of horse-traffic grit, sand or clinker assisted the animals to get a grip; in the early days of motor vehicles it assisted the treadless cover to grip. Today the need for grip is met by tyre construction. Research has produced a tread to meet almost any onor off-the-road condition and grit, ash or sand does little to assist traction. Gritting is a waste of time and money, leaving in its wake a cleaning-up task.

What should be used? I know of nothing superior to salt to melt ice or snow in its

early stages—salt flows easily through the spreader aperture on any type of equipment. I know that some highway engineers say it plays havoc with a road surface. But the fact is we are attacking a dangerous road in emergency circumstances where life and limb are in danger—this demands drastic action.

A vehicle fitted with a spreader or a spreader body travelling at 10 mph gives a 20ft-spread of salt at about ,-14th of an inch. One ton covers five miles in 30 minutes and almost certainly brings an immediate thaw.

Emergencies

Snow emergencies usually occur at about dawn or in the two hours before, and it is for this reason that chaos ensues. Early morning traffic spills onto the roads before the emergency routine has started, accidents occur, traffic becomes immobilized, timorous drivers abandon vehicles. Pre-salting is the answer: in most cases this will repel almost any early light fall, and it is recommended by the MoT and the Scottish Office. It allows the emergency service a breathing space.

Councillors frequently harangue officials to get priority for their wards in emergencies. This should not happen with snow clearing. The essential roads are those serving p.s.v. routes and hospitals—these must have priority. By sending vehicles off on the pre-arranged routes, not exceeding 20 miles in each case, one load will cover one route, and of course the route should start at the point nearest to the depot. The first vehicle should salt the road between the depot and the bus route. Those following will not only leave the depot with ease but will carry some of the salt on their wheels into their own routes.

To ensure an early start after an emergency call, it is wise to leave vehicles standing loaded the previous evening. I appreciate that this will mean loading on perhaps 30 occasions and not using the material, but then comes the time when it is required and the effort has been worth while. After all, by using a one cu.yd. loading shovel, a 5-ton vehicle can be loaded in less than five minutes.

In my experience when this routine is used main roads are open within two hours of the alarm call. Of course, this success depends on the number of vehicles in use, and I suggest that one 5-ton vehicle per 20 miles of main road is essential. From spot surveys I estimate that there is on average approximately a mile of main road per 1,000 head of population.

As it is not always simple to get money for this type of exercise, I suggest we look at the cost. The operation of a 5-ton tipping vehicle with an attendant will cost 50s per hour and for 20 miles of highway this will cost 2s 6d per mile. The cost of the material is about £1 per ton mile. In addition there is the cost of loading and a one cu.yd. shovel must be charged for during the time the driver is in attendance, whether or not he is loading. This charge is about 35s per hour. On average a call would last for three hours and he would load in that time a minimum of 50 tons. Therefore the cost would be about 2s per ton mile.

Of course, stand-by payments must be taken into consideration. To be safe the stand-by should operate during the 21-week period November 1 to March 21, and I suggest the payment should not be less than £1 per man per week. This will mean £42 per vehicle crew on two-man operation each season. We must assume four emergency calls each season, and this I feel is a minimum. The cost per call would therefore be 10 guineas and working on 20 miles per call this would mean lOs 6d per mile.

Therefore the all-inclusive rate for clearing the snow or ice hazard and keeping lines of communication open in cities works out at 35s per mile, a cost which reduces slightly as calls increase. The figures quoted are higher-than-average so that this cost per mile is on the high side. At first sight this may appear exhorbitant to councils but surely it is preferable to the alternative of allowing chaotic conditions to prevail and then when the snow is hard-packed turn out men and machines to break it, load it, and dump it. It is often difficult to clear more than one mile per vehicle per day by this method. Without the additional labour and loading costs this

will amount to not less than £14 per mile.

The difference between pre-planning and a hit-or-miss practice is that in the first case the costs are known in advance and have to be faced. The second method is less informative: accounts are rendered and passed for payment with a feeling of relief that the emergency is over and is a head-in-sand approach to the problem.

It is more efficient and more economic to pre-plan, use up-to-date methods, and active de-icing materials. This requires planned capital investment and a great deal of detailed work now. It cannot be left until December.