FOUR LEGS ON MY WAGON

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

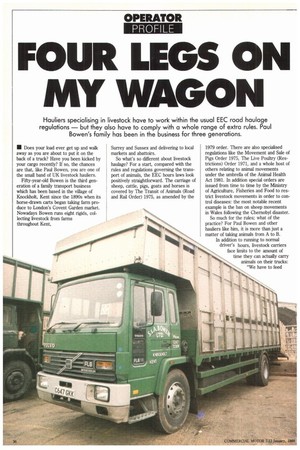

Hauliers specialising in livestock have to work within the usual EEC road haulage regulations — but they also have to comply with a whole range of extra rules. Paul Bowen's family has been in the business for three generations.

• Does your load ever get up and walk away as you are about to put it on the back of a truck? Have you been kicked by your cargo recently? If so, the chances are that, like Paul Bowen, you are one of the small band of UK livestock hauliers.

Fifty-year-old Bowen is the third generation of a family transport business which has been based in the village of ICnockholt, Kent since the 1890s when its horse-drawn carts began taking farm produce to London's Covent Garden market. Nowadays Bowen runs eight rigids, collecting livestock from farms throughout Kent, Surrey and Sussex and delivering to local markets and abattoirs.

So what's so different about livestock haulage? For a start, compared with the rules and regulations governing the transport of animals, the EEC hours laws look positively straightforward. The carriage of sheep, cattle, pigs, goats and horses is covered by The Transit of Animals (Road and Rail Order) 1975, as amended by the 1979 order. There are also specialised regulations like the Movement and Sale of Pigs Order 1975, The Live Poultry (Restrictions) Order 1971, and a whole host of others relating to animal movements under the umbrella of the Animal Health Act 1981. In addition special orders are issued from time to time by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food to restrict livestock movements in order to control diseases: the most notable recent example is the ban on sheep movements in Wales following the Chernobyl disaster.

So much for the rules; what of the practice? For Paul Bowen and other hauliers like him, it is more than just a matter of taking animals from A to B. In addition to running to normal driver's hours, livestock carriers face limits to the amount of time they can actually carry animals on their trucks: "We have to feed and water and unload them after 12 hours," says Bowen. This means that on long journeys livestock hauliers have to arrange "lairage" — a stopover paddock at a market or farm.

Bowen explains: "If we're going from Kent to the north of Scotland, we would ring up Carlisle market and say could we unload some stock for the night? Then the driver would have his rest, the animals could be fed and watered and reloaded in the morning." Most of Bowen's work comprises short runs between local farms and markets, so the company seldom needs lairage, but it is a common feature of long-distance livestock haulage.

The different types of animal have to be kept apart: "Say we take a load to market, we have to keep cattle separate from sheep, and sheep from pigs," says Bowen. Horned and polled (de-horned) cattle also have to be kept apart. This is normally done with removable internal dividers within the truck bodywork, or by placing different breeds on different deck levels within a multi-deck vehicle. To prevent the stock moving around too much in the lorry, drivers must also set up partitions every 3.6m when carrying cattle, and every 2.4 metres when hauling pigs or sheep.

DISINFECTANTS

On one of Bowen's 16-tonners a typical full load of fat cattle represents 14 animals on a single deck, or with two decks Bowen can carry up to 150 fat lambs. Once a truck gets to market it has to be washed out as soon as it unloads, using ministry-approved disinfectants to prevent the spread of any diseases: "There's ministry animal inspectors checking that you wash out after each trip. Its done for foot and mouth and all those diseases and is in the animal movement order. . it's always been that way," says Bowen.

The constant supervision and vehicle checks are not only restricted to markets: "If you'd been carrying animals with foot and mouth, or something like that, the ministry would also came and inspect the lorries being washed at the depot, and you'd have to steam them out," As with their counterparts in the vehicle inspectorate, the Ministry of Agriculture inspectors can put a truck off the road if an operator breaks the rules.

Alongside the ministry men there is also the RSPCA. According to Bowen: "They check for cruelty to stock, and that you haven't damaged them on the way to market." Satisfying the RSPCA is not always easy, says Bowen — particularly if the livestock haulier is dealing with a less-than-scrupulous farmer.

"Say a fanner rings up and says: 'I've got six cows to take to market'. You go there and load up and there's straw and mud down on the ground — you can't see what they're like as they come out. One might be an old animal with a damaged foot. When it gets to the market and is unloaded on concrete the ministry officials and vets can see everything — they can do the driver for bringing it. This is what we're fighting now. They do go back and summons the farmer, but I don't see why the driver should be summonsed for moving them," Bowen firmly believes that some farmers try it on: "What gets me is that a vet inspector gets five years training so he can spot anything. A driver doesn't have any training like that."

To ensure that his vehicles carry only healthy animals Bowen employs drivers with stock experience, who are likely to spot any sick animals: "Its easier to teach a stockman to drive than the other way round — we'd rather have a chap that's used to stock."

This recruiting policy seems to work, as Bowen has kept a clean record with the ministry.

The reluctance, or sheer bloody mindedness, of some animals to actually get onto a truck is well documented as any livestock driver will testify, but if an animal has been on a truck before it's usually less of a problem. Nonetheless, a swift kick in the knee from a bullock is still an occupational hazard for drivers.

Carrying livestock also requires a more gentle driving technique, says Bowen, with greater anticipation needed when approaching roundabouts and junctions, while smoother braking is necessary to avoid throwing the stock around and possibly damaging them. The movement of stock within the truck is also an important consideration when it comes to driving a lorry over a dynamic axle weigher, where a sudden surge by the animals could cause the unrealistic axle reading.

Operating with more stringent rules and regulations than the general haulage business, is livestock haulage less vulnerable to cowboy (sic) operators? "You still get them," claims Bowen. "The trouble is, you get a lot of farmers on cheap farm tax (so-called F Licences) who do their own transport, but they then try and do their neighbours. Its difficult to prove it to get a summons out on them. Also what's creeping in now, although not so much in this area, is these large double-deck cattle artics. People have only got two or three acres and they're taxing them under an F Licence. You know darn well they're doing it for other people," The disparity between the VED paid on vehicles licensed by farmers and those run by general hauliers has always been a sore point, particularly with the Road Haulage Association, which has campaigned hard for it to be ended. As a former chairman of the RHA's livestock group Bowen has frequently added his voice to this argument.

The gap between 0 arid F Licence VED rates has also come under scrutiny by the Treasury. In the 1987 Budget, VED for trucks run by farmers went up by an average of 12% while for general hauliers it was frozen.

This completed a three-stage plan to bring VED on F Licenced vehicles up to 60% of normal HGV tax. Even so, the current annual rate of £620 for a 16tonner taxed under an F Licence is still significantly lower than the £1,030 levied on a road haulier's 16-tonner.

WITHDRAWAL

Until now Bowen has been a conunitted Bedford buyer, but his eight-vehicle fleet now includes two Volvos. He likes the TL for its lightweight chassis, especially as full-height cattle bodies tend to bump up the kerbweight even with their alloy construction.

The recent withdrawal of Bedford from the civilian truck market forced Bowen to look around for an alternative marque: "I've never been a Leyland or Ford man, so what's the next lightest truck? Scania and Daf are heavy, so we got the Volvo," he says. Bowen currently runs an F6 and a C-registered FL6 with his Bedfords: "They do the job very well: they are heaiver than the TL but they should be more reliable. Bedford let themselves down with their engines; nothing else, as far as we are concerned — it has always been trouble with the engine."

David Brown's recent purchase of Bedford and his new company AWD, which is scheduled to re-introduce selected models in the summer, could, however, encourage Bowen to return to the marque he likes, especially as an AWL) TL could be fitted with a Cummins or Perkins engine: "We're looking at it closely," he says, but asks: "Are they going to offer a 17tonner?"

Along with most other rigid operators, Bowen is planning to take full advantage of the increased gross weight limit for two-axle rigids which comes into affect on 1 April, if only to claw back some of the payload lost through sideguards and spray supression equipment. "It's all extra weight," he says.

by Brian Weatherley