CONTROLLING TRANSPORT OPERATION

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Path fields Transport Ltd

by David Lowe MinstTA AMBIM DAVID OAKEY, the proprietor of this eight-vehicle haulage business at Alvescot, Oxford, has an enlightened view of transport operation that would do credit to many of his much larger contemporaries.

This enlightenment is something he has gained the hard way since 1967 when the business (originally started by his father with a horse and cart) had expanded to a nine-vehicle operation only to be reduced, rather sharply to one, through the loss of a main customer. Although this considerable loss was a severe blow at the time, David Oakey is now inclined to feel that it was a good thing because it brought home to him in no uncertain manner the pitfalls and dangers confronting a small haulage contractor.

He took over the business when his father died and on his own admission did not know much about it, having spent seven years in the RAF, but his intentions were "to set the world on fire". Intentions which soon took a hard knock, especially when he found himself back to driving his only vehicle.

He rebuilt the business, an all-tipper operation, based on ash carrying from power stations to breeze block manufacturers. and tennis court makers and

this now comprises some 65 per cent of his work. It is not, however, all for one customer — that lesson has been well learned — and besides the transport operation he is involved in the buying and selling of much of the material carried.

Am I profitable?

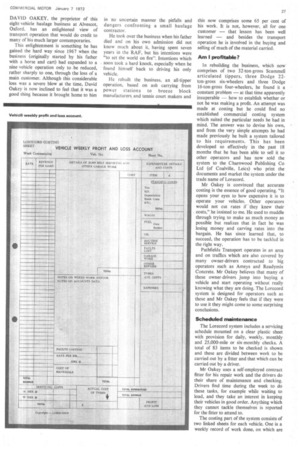

In rebuilding the business, which now comprises of two 32-ton-gross Scarnmell articulated tippers, three Dodge 22ton-gross six-wheelers and three Dodge 16-ton-gross four-wheelers, he found it a constant problem — at that time apparently insuperable — how to establish whether or not he was making a profit. An attempt was made at costing but he could find no established commercial costing system which suited the particular needs he had in mind. The answer was to devise his own, and from the very simple attempts he had made previously he built a system tailored to his requirements. This has been developed so effectively in the past 18 months that he has been able to sell it to other operators and has now sold the system to the Charnwood Publishing Co Ltd (of Coalville, Leics) who print the documents and market the system under the trade name of Lorecord.

Mr Oakey is convinced that accurate costing is the essence of good operating. "It opens your eyes to how expensive it is to operate your vehicles. Other operators would not cut rates if they knew their costs," he insisted to me. He used to muddle through trying to make as much money as possible but realizes that in fact he was losing money and carving rates into the bargain. He has since learned that, to succeed, the operation has to be tackled in the right way.

Pathfields Transport operates in an area and on traffics which are also covered by many owner-drivers contracted to big operators such as Ameys and Readymix Concrete. Mr Oakey believes that many of these owner-drivers jump into buying a vehicle and start operating without really knowing what they are doing. The Lorecord system is designed for operators such as these and Mr Oakey feels that if they were to use it they might come to some surprising conclusions.

Scheduled maintenance

The Lorecord system includes a servicing schedule mounted on a clear plastic sheet with provision for daily, weekly, monthly and 25,000-mile or six-monthly checks. A total of 83 items to be checked is shown and these are divided between work to be carried out by a fitter and that which can be carried out by a driver.

Mr Oakey uses a self-employed contract fitter for his repair work and the drivers do their share of maintenance and checking. Drivers find time during the week to do these tasks, for example while waiting to load, and they take an interest in keeping their vehicles in good order. Anything which they cannot tackle themselves is reported for the fitter to attend to.

The costing part of the system consists of two linked sheets for each vehicle. One is a weekly record of work done, on which are entries taken from the driver's record sheet and shown under the headings of customer, load from and to, material carried, quantity, ticket number, fuel and oil used — divided between own supplies and bought out supplies — drivers' expenses, weekly mileage and any tyre changes. The second sheet, which is placed in line with the first, has entries showing the rate for the job and the total revenue, servicing and standing costs and the crucial figures of total expenditure compared with total revenue. This shows the profit, or loss, for the vehicle for that week.

Standing costs for each vehicle are established by the normal methods and shown on the sheet, so tools depreciation. A gross wages figure is entered but tyre costs are estimated. Actual tyre costs are recorded on the sheet so that annual totals of estimated and actual tyre costs can be compared.

Sharing establishment costs

To arrive at an equitable figure for establishment costs between all the vehicles Mr Oakey compiled all the costs involved in operating the business into a total which was then divided by the total carrying capacity of the fleet. This gave a figure per ton of carrying capacity which was then multiplied by the carrying capacity of each vehicle to arrive at an establishment charge per vehicle. This too is entered on the weekly profit and loss sheet.

. Mr Oakey has found that his drivers take a very keen interest in the costs and the earnings of their vehicles and they are free to examine the cost sheets whenever they wish. This has engendered a spirit of rivalry between them to keep — so far as it is possible for them to do so — costs down and boost earnings by trying to get that extra load. Not, I might add, by breaking the law, which would not be tolerated.

In order to make it easier to translate the cost figures into comparisons David Oakey uses a Colplan graph to show the performance of individual vehicles, and the drivers are always popping into the office to see how they are doing. An instance of this interest was highlighted when a vehicle broke down for a period and its coloured line sunk to the bottom of the graph. The driver then worked enthusiastically to get it up again to its former level. Although such an example may suggest that drivers are tempted to ill-treat vehicles in these circumstances the evidence from the cost sheets is that they don't — because they can easily see that flogging a vehicle to the point of breakdown, or to excessive wear, has a greater downward effect on the magical line than getting an extra load has on the upward trend if it is necessary to flog the vehicle to get the extra load.

Costing too much to run

Besides the drivers' interest in these figures Mr Oakey has ,come to a few significant conclusions himself from keeping and studying his cost figures. The most important is that the two 32-ton artics which he purchased before getting the system established — because he understandably believed that with bulk traffics the bigger the load-carrying capacity the better the profit, etc etc — are an enormous burden to him because of the cost involved in operating them. He finds that the smaller vehicles give a much better return and if an odd load is lost the effect is not too dramatic. One load lost in a week with a big artic has a disastrous effect on the final weekly figure for that vehicle.

Mr Oakey concludes from this that the ideal vehicle for him to operate would be an 18-ton-gross machine, and in particular a Commer /Unipower six-wheeler giving a 13-ton payload which he has seen advertised at £3,100, a figure comparable with the average 16-ton-gross four-wheeler.

It is this type of thinking that illustrates the level of decision which can be taken when one has sufficient financial information of the right type to hand.

In addition to the costing system Mr Oakey has one or two other modern aids which save him time and' money and therefore increase the efficiency of his business. He uses a Philips pocket memo tape-recorder on which he can dictate reminders for himself or letters to be typed later. This is most useful when he is out in his car and has time to think. He also has a small electronic calculator which will add, subtract, multiply and divide. This tiny machine, costing under £100, is used for wages and invoice work and reduces what was previously two days' work per week to about half a day a week.

Final aid

A final aid to efficiency is the use of a Bramah tea and coffee maker which is installed in the office. Mr Oakey found that drivers were wasting time and money hanging about in the yard waiting for the kettle to boil, to wash cups and get a hot drink before setting out. The machine dispenses hot drinks instantly — and it is good coffee -so the delays are considerably reduced, there is no washing up and no wastage of tea, coffee and sugar.

Mr Oakey appears to find great satisfaction in being a small operator and has not much desire to expand to a big fleet — the satisfaction obviously derives from doing what he is doing well rather than attempting to do more, but less efficiently.