MOORE NOT LESS

Page 30

Page 32

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

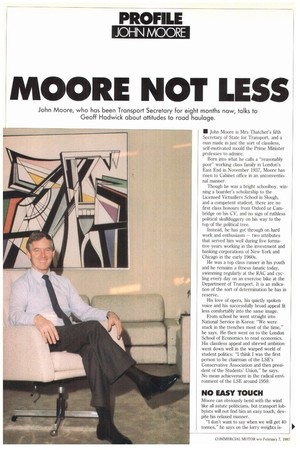

John Moore, who has been Transport Secretary for eight months now, talks to Geoff Hadwick about attitudes to road haulage.

• John Moore is Mrs Thatcher's fifth Secretary of State for Transport, and a man made in just the sort of classless, self-motivated mould the Prime Minister professes to admire.

Born into what he calls a "reasonably poor" working class family in London's East End in November 1937, Moore has risen to Cabinet office in an unconventional manner.

Though he was a bright schoolboy, winning a boarder's scholarship to the Licensed Victuallers School in Slough, and a competent student, there are no first class honours from Oxford or Cambridge on his CV, and no sign of ruthless political skullduggery on his way to the top of the political tree, Instead, he has got through on hard work and enthusiasm — two attributes that served him well during five formative years working in the investment and banking corporations of New York and Chicago in the early 1960s.

He was a top class runner in his youth and he remains a fitness fanatic today, swimming regularly at the RAC and cycling every day on an exercise bike at the Department of Transport. It is an indication of the sort of determination he has in reserve.

His love of opera, his quietly spoken voice and his successfully broad appeal fit less comfortably into the same image.

From school he went straight into National Service in Korea: "We were stuck in the trenches most of the time," he says. He then went on to the London School of Economics to read economics. His classless appeal and shrewd ambition went down well in the warped world of student politics: "I think I was the first person to be chairman of the LSE's Conservative Association and then president of the Students' Union," he says. No mean achievement in the radical environment of the [SE around 1959.

NO EASY TOUCH

Moore can obviously bend with the wind like all astute politicians, but transport lobbyists will not find him an easy touch, despite his relaxed manner.

"I don't want to say when we will get 40 tonnes," he says on the lorry weights is sue and harmonisation in 1992. "I'm not the 'Yes Minister' type. There are no proposals for change." He defends the derogation Britain has secured on the 40 tonne weight limit and still wants to wait to see the results of the bridge survey the DTp is carrying out to discover whether or not the nation's bridges are strong enough to carry 40 tonners.

Does he accept that many bridges could easily cope with 40 tonners today, as the transport officials of Brussels have already pointed out? "Well, we are going to publish our bridge report soon, and some bridges can clearly take 40 tonnes. However, the major shift to lorry freight transport, combined with other aspects of road use, means a number of bridges will clearly need some work. It's probably going to be a 15-year programme.

"But all this is not the issue. The bridges are only a factor in the debate. The issue is that Parliament, the Government, the country — whatever the economics — don't want 40 tonnes.

"I'm not going to try and butt my head against a parliamentary brick wall. That would be the action of an unwise politician," he says.

Moore likes to think things through, pondering the ramifications of an issue or decision.

For instance, why did he come back from America after only five years in the high-pressure, high-income world of investment banking and stockbroking in New York? "No-one could believe I wasn't staying. I had to keep explaining — 'No, I only want to stay for five years and understand how your society works.' The Americans have an opportunity society in one sense, and a very open one. They are very exciting and they are geared to success." He married an American too.

AUSTERITY

The Britain John Moore left was still recuperating from post-war austerity. He envied the material wealth of the American soldiers he met in Korea. He wanted to know how and why they did so well. Today, he still says he thinks about the way your background counts for nothing in the States, and how you get on by working hard and using your abilities to the full. "Too many people have a chip on their shoulder in Britain," he says of our class system. History weighs heavy on Britain and, according to Moore, sometimes we are over-timid as a consequence. We tend to be too frightened of change. "We are a very conservative society with a small c," he says.

In the scale of wet to dry, the Heath to Thatcher range of political sympathies in the Tory Party, Moore is classified as a definite dry. He is a champion of privatisation and of employee share ownership.