An Advanc Heavy-duty Synchromesh Design

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

riA MAJOR development in synchromesh systems for gearboxes, of parecular value in commercial vehicle applications, has been achieved by Smiths Motor Accessory Division, Edgware Road, London, N.W.2. Although essentially the same in principle as the original synchromesh first introduced in a private car gearbox some 30 years ago, the Smiths unit provides three times as much frictional working surface without taking up any more space inside the gearbox. Many of the commercial-vehicle gearboxes produced today are still unsynchronized, making it necessary to double declutch at every gear change and having the disadvantage that the high inertia of the clutch friction plate may make an upward gear change impossible at the desired moment, when climbing a gradient of medium severity, even though enough power is available for the vehicle to pull a higher gear. It has been the practice of heavyvehicle manufacturers to fit clutch stops and these, when properly used, fulfil the function of killing this clutch-plate inertia. But it has been my experience that, far from the clutch stop being used properly, only about one driver in 10 knows when a vehicle has a stop fitted and even fewer know what its real purpose is. Because of this, and to simplify manufacture and keep costs down, the clutch stop is disappearing from the scene. Several attempts have been made to produce a heavy-duty synchronized gearbox but, although these are very efficient when new, the synchronizing effect can very largely be lost after only a few thousand miles.

The Advantages

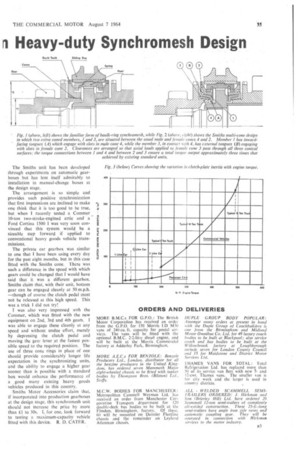

The new Smiths unit should go a long way towards overcoming this problem as the extra working surface it provides will also give longer life. The diagram in Fig. 1 shows the familiar type of synchromesh; to make this unit efficient at this size, very high gear-lever operating pressures will be required. By utilizing the same amount of space for the Smiths unit, it can clearly be seen in Fig. 2 that a much larger effective working area is provided, this demanding a lower lever effort and promising a longer operational life. In Fig. 3 are typical inertia curves which give some idea of the power which must be absorbed when changing gears on various sizes of vehicle. This power is absorbed in two ways at the moment: (a) through the frictional losses at the spigot shaft and those of the engine generally; this is the double-declutch method. (b) Through a braking force applied to the clutch-stop disc or drum. The first method requires time for the moving masses of the engine and clutch assemblies to slow down, which can be a surprisingly long period on some engines, while the second demands a fair amount of skill to be effective.

The Smiths unit has been developed through experiments on automatic gearboxes but has lent itself admirably to installation in manual-change boxes at the design stage.

The arrangement is so simple and provides such positive synchronization that first impressions are inclined to make one think that it is too good to be true, but when 1 recently tested a Commer 10-ion two-stroke-engined artic and a Ford Cortina 1500 1 was very soon convinced that this system would be a sizeable step forward if applied to conventional heavy goods vehicle transmissions.

The private car gearbox was similar to one that 1 have been using every day for the past eight months, but in this case fitted with the Smiths cone. There was such a difference in the speed. with which gears could be changed that I would have said that it was a different gearbox. Smiths claim that, with their unit, bottom gear can be engaged cleanly at 50 m.p.h. —though of course the clutch pedal must not be released at this high speed. This was a trick 1 did not try!

I was also very impressed with the Commer, which was fitted with the new equipment on 2nd, 3rd and 4th gears, was able to engage these cleanly at any speed and without undue effort, merely by depressing the clutch pedal and moving the gear lever at the fastest possible speed to the required position. The use of three cone rings in place of one should provide considerably longer life expectation in the synchronizing units, and the ability to engage a higher gear sooner than is possible with a standard box would enhance the performance of a good many existing heavy goods vehicles produced in this country.

Smiths Motor Accessories claim that, if incorporated into production gearboxes at the design stage, this synchromesh unit should not increase the price by more than £11 to 30s, 1, for one, look forward to testing a maximum-capacity vehicle fitted with this device. R. D. CATER.