DRAWBARS DRIVING

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

LEFT HAND DOWN A BIT

Mi The HGV test gives credence to the claim that an articulated vehicle is the most difficult to drive and manoeuvre. Yet few drivers with a Class 1 HGV licence could claim to be able to reverse a drawbar combination in a confined area with the same degree of confidence or precision that they are able to demonstrate with an articulated vehicle.

In fact most would have to admit that they have little or no idea of the rudiments of controlling the direction of a reversing drawbar trailer.

The HGV test does not even consider the operation of the drawbar, so driving schools tend no to include this option in their training. It is, however, not the Class 1 driver who is most likely to be faced with the problem. Only a day after gaining his Class 3 licence, a driver could be driving a drawbar combination up to 18.28m (60ft) long.

Driving forwards normally should not present too much of a problem as most drawbar trailers are set up to follow closely in the path of their prime movers and only cut in to any marked degree on sharp turns; but reversing is quite a different matter. To further complicate the situation there are four main types of drawbar trailer and many variations of each. The conventional "drag" is a long-wheel trailer running on two or more axles. Its leading axle is a rigid beam mounted on a ball-race turntable fitted with a fixed-length A-frame.

The "trombone" allows close coupling and the achievement of a longer overall platform length with a conventional trailer. Its extending A-frame provides the required clearance between the rear of the prime mover and the front of the trailer during manoeuvres.

The "seesaw" type of trailer has twin axles located centrally and may allow a longer platform length than the conventional trailer with a fixed A-frame.

The fourth type is less common than the other three. Its steering axle is a "dolly" complete with A-frame and fifth wheel coupling. When attached to a semitrailer it forms a conventional trailer.

Drawbar operation forms a growing segment of road transport, but in Britain is quite different to Continental operation. On the first count it is limited to 32.5tonne operation. Secondly, probably more than 90% include a demount system, which offers greater operational flexibility and volume.

A conventional drawbar combination provides up to 20% more platform length than an artic; with an extending A-frame this can be increased to 27%. Operation at 32.5 tonnes also avoids the 4.2m height restriction of heavier GVW articulated vehicles.

As few driving schools are able to provide tuition it falls on the manufacturers' shoulders to promote their cause. We visited a demount manufacturer based in Peterborough which offers just such training for its customers' drivers.

Ray Smith, the UK agent for the Dutch-designed Contar sliding A-frame drawbar coupling, provides this service free of charge. Alan Morton, Ray Smith's training officer, explains: "Drawbar combinations do not conform to any common After a brief chat in Alan Morton's office we set out into the Peterborough traffic in the company's Daf 2100 demonstrator. True to form, I.fell into the trap which claims the majority of Class 1 drivers.

Treating the combination as an artic took up much more of the road width than was necessary to avoid most obstacles. On approaching a 1-junction with a tight left turn I positioned the vehicle correctly to avoid clipping the kerb, but again my artic driving habits prevailed as I pulled the front of the vehicle well forward into the apex of the corner.

What I had failed to realise fully is that although the prime mover may have a similar lock to a tractive unit, the turning circle is much larger due to the longer wheelbase. If I was having problems going forward, what about reversing? Fortunately I was in good hands!

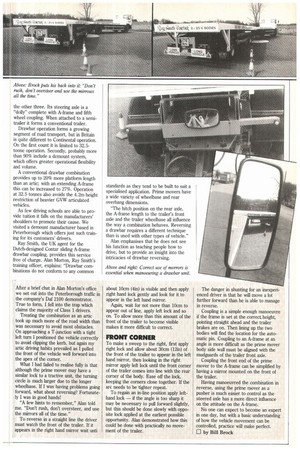

"A few hints to remember," Alan told me. "Don't rush, don't oversteer, and use the mirrors all of the time."

To reverse in a straight line the driver must watch the front of the trailer. If it appears in the right hand mirror wait unti standards as they tend to be built to suit a specialised application. Prime movers have a wide variety of wheelbase and rear overhang dimensions.

"The hitch position on the rear axle, the A-frame length to the trailer's front axle and the trailer wheelbase all influence the way a combination behaves. Reversing a drawbar requires a different technique than is used with other types of vehicle."

Alan emphasises that he does not see his function as teaching people how to drive, but to provide an insight into the intricacies of drawbar reversing.

Above and right: Correct use of morrors is essential when manoeuring a drawbar unit.

about 10cm (4in) is visible and then apply right hand lock gently and look for it to appear in the left hand mirror.

Again, wait for not more than 10cm to appear out of line, apply left lock and so on. To allow more than this amount of the front of the trailer to become visible makes it more difficult to correct.

FRONT CORNER

To make a sweep to the right, first apply right lock and allow about 30cm (12in) of the front of the trailer to appear in the left hand mirror, then looking in the right mirror apply left lock until the front corner of the trailer comes into line with the rear corner of the body. Ease off the lock, keeping the corners close together. If the arc needs to be tighter repeat.

To regain an in-line position apply lefthand lock — if the angle is too sharp it may be necessary to pull forward slightly, but this should be done slowly with opposite lock applied at the earliest possible opportunity. Alan demonstrated how this could be done with practically no movement of the trailer. The danger in shunting for an inexperienced driver is that he will move a lot further forward than he is able to manage in reverse.

Coupling is a simple enough manoeuvre if the frame is set at the correct height, pointing straight ahead and the trailer brakes are on. Then lining up the two bodies will find the location for the automatic pin. Coupling to an A-frame at an angle is more difficult as the prime mover body side wall must be aligned with the mudguards of the trailer front axle.

Coupling the front end of the prime mover to the A-frame can be simplified by having a mirror mounted on the front of the trailer.

Having manoeuvred the combination in reverse, using the prime mover as a pusher is much easier to control as the steered axle has a more direct influence on the attitude on the A-frame.

No one can expect to become an expert in one day, but with a basic understanding of how the vehicle movement can be controlled, practice will make perfect.