Where

Page 59

Page 60

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Contract Hauliers

Fall Down

Failure to Appreciate the Expenses Involved in Contract-A Work May Turn an Expected Profit into a Loss

IHAVE frequently referred to the precautions which a haulier should take when entering into a contract of haulage which is to be the basis of an application for a contract-A licence. I have warned readers against the folly of entening into such a contract when the.terms do not guarantee a minimum annual payment sufficient to cover estimated expenditure and to show a margin of profit. In particular, I have pointed out that a contract the basis of which is tonnage with no agreement as to the minimum quantity per annum, is risky.

I have an example of underestimating t■osts for contract-A carriage before me. It came about in connection with a man I met recently. A year previously he had told me that he was thinking of taking out a contract for the haulage of cattle foods. He did not give me details at the time, otherwise 1 might have helped him to avoid the troubles with which he was eventually beset.

He told me at eur second meeting that he was most dissatisfied with the way matters were going. He said that he started the contract quite well and was making a fair profit for a time but that it had fallen off badly.

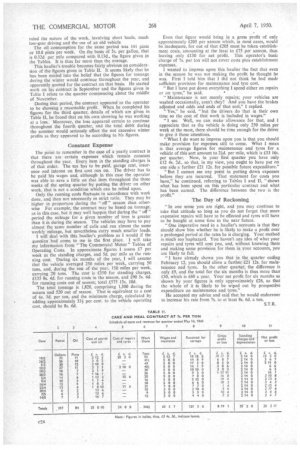

At that time, little more could be done because he had no detailed figures with him. I gathered, however, and correctly as events showed, that it was the seasonal fluctuation in traffic in cattle foods that had caused him trouble. He came to see me soonafterwards with his summarized accounts for two quarters. His figures appear in Tables I and II.

It is of interest to study the figures as they are, for they contain, in themselves, certain lessons which can be amplified later. The vehicle was not large, a three-Loaner which he had bought used some little time ago for about £250Q. The contract was for the cartage of oil cake and meal, and so on, and was, of course, for a year. He had obtained a contract-A licence.

The first thing to do in a case like this is to examine the headings. The most obvious deficiency is the figure for mileage. I gathered that the work was entirely short-distance haulage, being that of loading the meal and cake at a contractor's warehouse and distributing it to farmers within a 10-mile radius.

This haulier had never thought it worthwhile to keep any record of his mileage, but he told me that it amounted to approximately 250 per week. If it be taken that an average journey is about eight miles, that a load is three tons and the average is 16-17 loads per week, then the figure of mileage appears to be almost correct.

There is a column for petrol apd oil and their cost, one for expenditure on maintenance and tyres, and another for work done, the latter being recorded as total tonnage. The next heading is "Wages and insurance," and after that a column for receipts. I should state that the rate was flat at 7s. per ton.

Next comes " Gross profit." A brief examination of the figures shows that this sum is arrived at by deducting front the receipts the total of expenditure on wages and insurance, repairs and tyres and petrol and oil. Obviously, there is a good deal to be accounted for under., this heading before we arrive at net profit, but this deficiency is made up to some extent under the heading of "Standing charges" and "Depreciation."

What this operator calls standing charges comprises tax, £30 per annum: insurance, £38; garage rent, £15; and depreciation, £52. The total is £135, which is £2 14s, per week, as set down in column 10. Deducting £2 14s_ from the gross profit gives the figure for net profit, This is entered in the last column.

There are some notable and serious omissions in the schedule of costs. One of these is the establishment costs. As these are likely to amount to at least £1 10s. per week, their inclusion would make the picture presented by these figures even less satisfactory.

It is rather interesting to analyse this operator's figures for petrol and oil consumption. It will suffice if I take into consideration only the winter quarter, the one which is represented by the figures in Table I. The total consumption of petrol during the 13 weeks was 368 gallons, equivalent to 28.3 gallons per week. For 250 miles that is equivalent to 8.83 m.p.g. and, assuming petrol to cost Is. I Id. per gallon. the cost per mile for fuel is 2.6d., a figure considerably in excess of the average of 1.53d. quoted in "The Commercial Motor" Tables of Operating Costs. This excess cost is to a certain extent to be expected, having in mind the nature of the work, involving short hauls, much low-gear driving and the use of an old vehicle.

The oil consumption for the same period was 141 pints or 10.8 pints per week. On the basis of 5s. per gallon, that is 0.32d per mile compared with 0.13d., the figure given in the Tables. It is thus far more than the average.

This haulier's trouble becomes fairly obvious on consideration of the figures given in Table II. It seems likely that he has been misled into the belief that the figures for tonnage during the winter would continue throughout the year, and apparently quoted for the contract on that basis. He started work on his contract in September and the figures given in Table I relate to the quarter commencing about the middle of November.

During that period, the contract appeared to the operator to be showing a reasonable profit. When he completed his figures for the third quarter, details of which are given in Table II, he found that on his own showing he was working at a loss. Moreover, the loss appeared certain to continue throughout the fourth quarter, and the total debit during the summer would seriously affect the not excessive winter profits as they appeared to be according to his figures.

Constant Expense

The point to remember in the case of a yearly contract is that there are certain expenses which remain constant throughout the year. Every item in the standing charges is of that order. The tax has to be paid, garage rent, insurance and interest on first cost run on. The driver has to be paid his wages and, although in this case the operator was able to save a little on that item throughout the three weeks of the spring quarter by putting the driver on other work, that is not a condition which can be relied upon.

Only the running costs fluctuate in accordance with work done, and then not necessarily in strict ratio. They may be higher in proportion during the " off " season than otherwise For example, the contract may be based on tonnage, as in this case, but it may well happen that during the " off " period the mileage for a given number of tons is greater than it is during the season. The vehicles may have to pay almost the same number of calls and run almost the same weekly mileage, but nevertheless carry much smaller loads. I will deal with this haulier's problem as I would if the question had come, to me in the first place. I will take my information from "The Commercial Motor" Tables of Operating Costs. In approximate figures I assess £7 per week as the standing charges, and 5d. per mile as the running cost. During six months of the year. I will assume that the vehicle averaged 250 miles per week, carrying 50 tons, and, during the rest of the year, 150 miles per week, carrying 20 tons. The cost is £350 for standing charges, £135 8s. 4d, for running costs in the season. and £90 5s. 6d. for running costs out of season; total £575 I3s. 10d. The total tonnage is 1,820, comprising 1,300 during the season and 520 out of season. That is equivalent to a cost of 6s. 3d. per ton, and the minimum charge, calculated by adding approximately 33i per cent. to the vehicle operating cost, should be 8s. 6d. Even that figure would bring in a gross profit of only approximately £205 per annum which, in most cases, would be inadequate, for out of that £205 must be taken establishment costs, amounting at the least to £75 per annum, thus leaving only £130 for net profit. This operator's basic charge of 7s. per ton will not cover costs plus establishment expenses.

I wanted to impress upon this haulier the fact that even in the season he was not making the profit he thought he was. First I told him that I did not think he had made sufficient provision for maintenance and tyre cost.

" But I have put down everything I spend either on repairs or on tyres," he said. • "Maintenance is not merely repairs; your vehicles are washed occasionally, aren't they? And you have the brakes adjusted and odds and ends of that sort," I replied.

"Yes," he said, "but the drivers do that in their own time so the cost of that work is included in wages."

"1 see. Well, we can make allowance for that, and I appreciate that as the vehicle is doing only 250 miles per week at the most, there should be time enough for the driver to give it those attentions.

"What 1 do want to impress upon you is that you should make provision for expenses still to come. What I mean is that average figures for maintenance and tyres for a vehicle of this sort amount to 21d. per mile, which is £33 16s. per quarter. Now, in your first quarter you have only £12 4s. 2d., so that, in my view, you ought to have put on one side a further £21 12s. for possible future expenditure."

"But I cannot see any point in putting down expenses before they are incurred. That statement for costs you have," he continued, referring to Tables I and II, "shows what has been spent on this particular contract and what has been earned. The difference between the two is the profit."

The Day of Reckoning

"In one sense you are right, and you may continue to take that attitude so long as you do not forget that more expensive repairs will have to be effected and tyres will have to be bought at some time in the near future.

"One imperative need in a haulier's accounts is that they should show him whether he is likely to make a profit over a prolonged period at the rates he is charging. Your method is much too haphazard. You haven't any idea of what your repairs and tyres will cost you, and, without knowing them and making some provision for them in your accounts, you are likely to fall.

"I have already shown you that in the quarter ending February 12, you should allow a further £21 12s. for maintenance and tyres. In the other quarter, the difference is only £9, and the total for the six months is thus more than £30, which is £60 a year. Your net profit for six months as shown by your figures is only approximately £26, so that the whole of it is likely to be wiped out by prospective expenditure on maintenance and tyres."

He accepted my advice and said that he would endeavour to increase his rate from 7s. to at least 8s. 6d. a ton.