ACCELERATE HANDLING

Page 28

Page 29

Page 30

Page 31

Page 32

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Ind RAISE

PRODUCTION

By A. E. Sherlock-Mesher

TIME studies are said to have shown that handling accounts for 75 per cent, of the total hours involved in a production cycle. In me sense that they are non-productive, these hours are wasted. To them must be added man and machine-hours lost in bottle-necks, caused by the failure of internal transport to bring material to the machines and remove finished or partly processed work rapidly enough to enable a steady output to be maintained.

Mass production is a comparatively new development in this country, and in a number of cases the advance in handling technique has not fully kept pace with progress in manufacturing methods. The war forced large-scale production on concerns Which had not previously contemplated it and created problems that only mechanical aids to handling could satisfactorily solve. The most efficient manufacturing unit is one in which the ratio of production-tohandling time is high. To achieve that end, scientific use must be made of the latest devices for accelerating internal transport.

Alternatives in Mechanization Handling can be mechanized by employing conveyors— overhead or floor mounted—or industrial trucks, or both. Where consecutive processes are performed in different buildings in a works, a continuous conveyor system is impracticable and the industrial truck provides the obvious solution of the problem of maintaining flow production. Alternatively, the internal transport vehicle can be used as a feeder to the conveyor, bringing in raw materials at one end and taking off finished products at the other.

Loading and unloading account for a substantial proportion of the• time involved in handling. Idle periods for the vehicle and driver can be much reduced by using stillages in conjunction with trucks having elevating platforms. A stillage can be placed beside a machine, and work, having been processed, can be stacked on it in readiness for the arrival of the industrial truck.

Alternatively, products can be assembled an the s;illage, which then serves the same purpose as a conveyor belt. The assembling of -.;enerating sets may be quoted as an example of suitable work for the employment of stillages.

Trailers can be made to perform much the same function as the'stillage, and both can be specially designed to handle a wide variety of products.

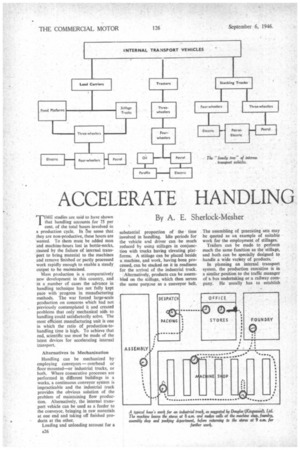

In planning an internal transport system, the production executive is in a similar position to the traffic manager of a bus undertaking or a railway company. He usually has to establish

defined routes and to decide upon the frequency of journeys, taking into consideration the character, weight, and cubic capacity cf the materials to be transported. Economic time lags have to be determined and the popular method is to prepare time and toad charts aril to co-oalinate them with a master plan.

Douglas (Kingswood), Ltd., has devoted particular study to the science of mechanical handling, and in an excellent booklet entitled "The Douglas Internal Transport System," outlines a typical hour's work with an industrial truck.

At 8 a.m. the driver leaves the stores with parts tor machining, and at 8.5 a.m, picks up finished work for assembly. At 8.15 a.m. the truck calls at the foundry and collects castings for machining. From there it travels to the machine shop, arriving at 8.25 a.m., . and, after dropping castings, picks up more finished parts for the assembly shop. At 8.40 a.m. an assembled unit is collected and delivered to the packing department, and 9 at-n. sees the vehicle back at the control point, ready for the next journey.

This timetable is translated into pictorial form in an accompanying diagram reproduced from the Douglas booklet.

According to the Douglas concern, the cost of the truck and the wages of its driver equa: the cost of employing three men pulling handcarts. The work done by mechanical means is, however, equal to that carried out by 10 labourers using old-fashioned methods.

Apart from being totally inefficient, manual methods of handling in the factory have a psychological disadvantage. The man' whose sole occupation in life is the manipulation of a handcart can hardly be blamed if he shows little interest in his work. On the other hand, if he be placed in charge of a mechanical truck, his status is immediately raised, and, as a semi-skilled worker, his earning capacity becomes greater.

With industrial relationships in their present delicate state of balance, this consideratioa is extremely important. The mechanical truck also scores over the handcart in that it can easily be operated by female labour.

Everyday observation shows that the use of mechanical handling is by no means confined to manufacturing industries. Docks, railway stations, timber yards, aerokomes and other distributive centres all employ industrial trucks to speed up handling.

Arsenals and stores containing highly inflammable materials have their own special problems of internal transport, of which a satisfactory solution is provided by the oil-cngincd industrial truck or tractor, having flame-proof exhaust and electrical systems. • An interesting example of the employment of industrial trucks in retail trade is to be found at Harringay

and White City dog-racing tracks. Because of the location of the bars at those stadiums, large lorries carrying beer cannot approach them closely. Therefore, South London Brewery, Ltd., uses Planet tractors, working in conjunction with a train ot trailers, to haul crated beer from the lorry to the bars. The short-distance vehicle also solves passenger-transport problems on large public recreational estates. Who does not remember the welcome relief for tired feet afforded by the electric runabouts at the great Wembley Exhibition in 1924?

Some 20 years later we find Planet oil-engined tractors at Whipsnade Zoo, hauling special passenger trailers made by Barnards, Ltd., of Norwich. Similar outfits are employed at Butlin's Holiday Camp at Filey. Whatever the cargo, . the industrial truck meets the need for shOrt-distance transport.

I can visualize small tractors, with passenger-carrying trailers, as a valuable _adjunct to large works, such as the Ford plant at Dagenham, where parties of visitors are frequently conducted on inspection tours.

There are other uses for the industrial truck, not directly concerned with loadcarrying. For instance, it can be equipped with sprinkling and sweeping apparatus for cleansing floors in workshops and roads on factory estates. It can also be converted to serve the cause of fire protectkon in works. Again, with a small manually operated tipping body, the industrial truck becomes an excellent little, refuse collector for service in factories and large distribution centres.

Tractors can be used to replace light locomotives for shunting railway wagons on sidings, where the track is buried in the road. At least one manufacturer markets a tractor claimed to be capable of shunting railway wagons weighing 80 tons gross. industrial. tractors frequently have large steel bufferplates fitted at the front, as well as towing hooks at the•rear, so that they can be used for either pushing or pulling.

Seeking Perfection

What are the principal characteristics which the production engineer and the distributor seek in an industrial truck? The most desirable feature is probably ease of operation and maintenance, followed closely by cost considerations. Reliability is another vital asset, because a breakdown of internal transport in a sensitively tuned production system will cause chaos. Ease of starting is important, too, particularly where machines are operated by women,

A low platform is also preferable, to avoid unnecessary lifting—another vital matter where female operatives are largely employed. Mechanical means for the rapid elevating of platforms must be provided on stillage trucks.

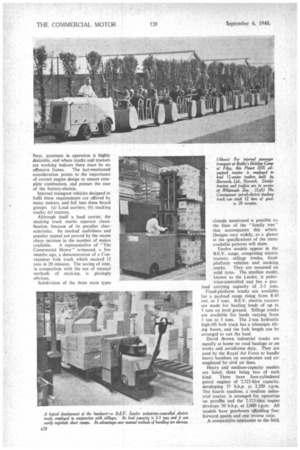

A high degree of manceuvrability is a further requirement, and the driver mast be afforded a good all-round view. Next, quietness in operation is highly desirable, and where trucks and tractors are working indoors there must be no offensive fumes. The last-mentioned consideration points to the importance of correct engine design to ensure complete combustion, and presses the case of the battery-electric.

Internal transport vehicles designed to fulfil these requirements are offered by many makers, and fall into three broad groups: (a) Load carriers; (b) stacking trucks: (c) tractors.

Although itself a load carrier, the stacking truck merits separate classification, because of its peculiar characteristics. Its marked usefulness and popular appeal are proved by the recent sharp increase in the number of makes available. A representative of The Commercial Motor" witnessed, a few months ago, a demonstration of a Conveyancer fork truck which stacked 12 Ions in 20 minutes. The saving of time, in comparison with the use of manual methods of stacking, is glaringly obvious.

Subdivision of the three main types already mentioned is possible on the lines of the "family tree" that accompanies this article. Designs vary widely, as a glance at the specifications of the many available patterns will show.

Twelve models appear in the B.E.V. range, comprising electric tractors, stillage trucks, fixedplatform vehicles and stacking trucks. They are mounted on solid tyres. The smallest model, known as the Leader, is pedestrian-controlled and has a payload carrying capacity of 2-3 tons.

Fixed-platform trucks are available for a payload range rising from 8-10 cwt. to 3 tons. B.E.V. electric tractors are made for hauling loads of up to 5 tons on level ground. Stillage trucks are available for loads varying from I ton to 5 tons. The 2-ton hydraulic high-lift fork truck has a telescopic tilting boom, and the fork length can be arranged to suit the load.

David Brown industrial trucks are equally at home on road haulage or on works and aerodrome duty. They are used by the Royal Air Force to handle heavy bombers on aerodromes and arc employed by civil air lines.

Heavy and medium-capacity models are listed, there being two of each kind. Three have four-cylindered petrol engines of 2.523-litre capacity, developing 37 b.h.p. at 2,200 r.p.m. The fourth machine, a medium industrial tractor, is arranged for operation on paraffin and the 2.523-litre engine develops 30 b.h.p. at 2,000 Lp,m. All models have gearboxes affording four forward speeds and one reverse ratio.

A comparative newcomer to the field.

the Brush Pony three-wheeled electric vehicle has been specially designed for milk distribution, but is equally suitable for operation in the works, and was, in fact, developed from a works truck. The Pony has the platform (21f ins, from the ground) at the rear and can turn in a 15-ft. circle. It is mounted on 18-in. by 7-in, pneumatic tyres and is designed to deal with a payload of 18 cwt.

The Cleco stillage truck is intended for a 2-ton payload and has a platform height of II ins, in the lowest position and 15 ins, when raised. The platform io 4 ft. 6 ins, long and 2 ft. wide. With an overall length of 10 ft. 6 ins., width of 2 ft. 8i ins, and a wheelbase of 5 ft. 8 ins., the machine can turn in a circle of 12-ft. 6-in. diameter. Steering is by vertical tiller.

On level ground the truck is capable of a speed of 6-7 m.p.h. and can deal with gradients of up to 1 in 8. The controller provides .three speeds for

ward and reverse, with automatic delay action and hand-grip preselector.

Sole representative of the petrolelectric in the field of industrial trucks, the Conveyancer is a fork truck for 2-ton loads. A four-cylindered petrol engine of 1,772 c.c. is directly coupled to a d.c..generator. The truck is driven electrically by a d.c. motor, flexibly coupled to a double-reduction front axle. By driving on the front axle and steering the rear wheels, a remarkable degree of manceuvrability is obtained. This machine was described in "The Commercial Motor" on July 5.

A newcomer among stacking trucks, the Coventry Climax .is available in six models, with load-lifting capacities ranging from 1,500 lb. to 6,000 lb. They were described in the issue of "The Commercial Motor" dated August 9.

Four Douglas models are offered. Types 125A and 126A are both for 30-cwt. payloads and have fixed platforms, the difference between them being in the loading height. The 125A is a low-loading model with a platform height of 10A ins., whereas in the 126A the platform is 1 ft. 6-1,i ins, from the ground. There are two stillage trucks, both of 25-cwt. payload capacity; I27A is a low-loading model and 128A has a high-level platform. The wellknown Douglas horizontally opposed twin-cylindered, air-cooled, side-valve petrol engine of 596 c.c. is employed in all models.

The Lansing Bagnall concern has introduced a new tractor to haul loads up to 25 tons. It was described in "The Commercial Motor" on August 23.

Three tractors and four load carriers figure in the Mercury range. The biggest tractor, known as the 25 A.M. type, is claimed to be capable of pushing 80 tons on railway trucks and has a four-cylindered petrol engine of 3.518-litre capacity.

The load carriers are made for payloads ranging from I ton to 2 tons, and all have four-cylindered petrol engines, varying in piston-swept volume from 933 c.c. to 1.802 c.c. All have gearboxes affording three forward speeds and a reverse ratio. Another new fork truck is the Me rlift, described on August 23.

The Planet range is wide and the maker has devoted special attention to the development of oil-engined tractors. These are at work in oilfields and on other duties where the fire risk is high. The oil engine is of 1.63,-litre piston-swept volume and has two cylinders. The gearbox affords four forward speeds and a reverse ratio. There is also a lighter tractor known aS the C type, which has a four-cylindered petrol engine of 1A72-litre capacity.

Planet load carriers are available with either pneumatic or solid tyres, the payload being 15 cwt_ in the former case and 1 ton in the latter. Like the C-model tractor, the load carriers have 1.172-litre petrol engines and three forward speed gearboxes.

• Reliance trucks and •tractors are well known to industrial users and are made in eight models. The 14/SL, H/RL, FI/SSL. H /SRL and H/TSL types are all for 1-ton or 24-ton payloads, according to whether a single-cylindered 600 c.c. engine or a twin-cylindered 750 c.c. power unit is fitted. All these models have air-cooled power units with chain transmission and gearboxes affording two forward speeds and a reverse ratio. In the II/2 and HT2/B tractors and the FWB model, the driving wheels are at the rear, whereas in the types mentioned earlier, they are in the front. These three patterns also differ in that they have four-cylindered water-cooled engines of 1.802-litre piston-swept volume and three-forward-speed gearboxes.

In this article it has not been possible to do more than display the " goods " and point to their uses. The next stage is for the intending operator to make his selection from the range available. according to his special requirements.

[Since this article was prepared, a new Douglas high-lift truck has been announced, and was described in this journal on August 301