Slowing down

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

the speeding up

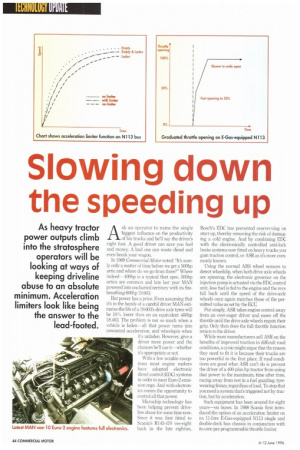

A74( an operator to name the single biggest influence on the productivity of his trucks and he'll say the driver's right foot. A good driver can save you fuel and money, A bad one can waste diesel and even break your wagon. In 1989 Commercial Motor noted: "It's surely only a matter of time before we get a 500hp artic and where do we go from there?" Where indeed 400hp is a typical fleet spec, 500hp artim are common and late last year MAN powered into uncharted territory with its firebreathing 600hp 19.603. But power has a price. Even assuming that it's in the hands of a careful driver MAN estimates the life of a 19.603's drive axle tyres will be 10% lower than on an equivalent 460hp 18,463. The problem is not so much when a vehicle is laden—all that power turns into unwanted acceleration, and wheelspin when ifs unladen. However, give a driver more power and the chances he'll use it—whether it's appropriate or not. With a few notable exceptions most engine makers have adopted electronic diesel control (EDC) systems in order to meet Euro-2 emission regs. And with electronics comes the opportunity to control all that power. Microchip technology has been helping prevent driveline abuse for some time now. Since it was first fitted to Scania's R143-470 vee-eight back in the late eighties, Bosch's EDC has prevented overrevving on start up, thereby removing the risk of damaging a cold engine. And by combining EDC with the electronically controlled anti-lock brake systems now fitted on heavy trucks you gain traction control, or ASR as it's more commonly known. Using the normal ABS wheel sensors to detect wheelslip, when both drive axle wheels are spinning, the electronic governor on the injection pump is actuated via the EDC control unit, less fuel is fed to the engine and the revs fall back until the speed of the drive-axle wheels once again matches those of the permitted value as set by the ECU. Put simply, ASR takes engine control away from an over-eager driver and eases off the throttle until the drive axle wheels regain their grip. Only then does the full throttle function return to the driver. While most manufacturers sell ASR on the benefits of improved traction in difficult road conditions, a cynic might argue that the reason they need to fit it is because their trucks are too powerful in the first place. If road conditions are good what ASR can't do is prevent the driver of a 400-plus hp tractor from using that power to the maximum, time after time, racing away from rest in a fuel guzzling, tyrewearing frenzy, regardless of load. To stop that you need a system that's triggered not by traction, but by acceleration. Such equipment has been around for eight years—on buses. In 1988 Scania first introduced the option of an acceleration limiter on its 11-litre E-Gas-equipped N113 single and double-deck bus chassis in conjunction with its own pre-programmable throttle limiter. There are two good reasons why Scania wants to control the acceleration and throttle application on its rear-engined buses. First, PCV chassis with transverse engines can suffer from oscillation in the engine suspension or throughout the entire power train if the throttle is applied too fast.

So changes in throttle setting have to be gentle—irrespective of how quickly the driver pushes the pedal down.

Second, like trucks, buses have become increasingly more powerful over the past decade. And if you accelerate too fast in a bus you're likely to find all your passengers in a heap at the back!

With the throttle limiter there is a built-in delay , controlled by the ECU, which operates at 800rpm; lower than the lowest speed (980rpm) at which the N113's Voith or ZF gearbox switches from hydraulic to mechanical gear changing.

Starting off from rest in drive with hydraulic gear changing the throttle opening is fast up to 50% of the "wide open" setting, in order to give good acceleration away from the bus stop, then it's opened more slowly up to wide open.

When in drive with mechanical gear (in other words over 800rpm) the throttle opening is initially slow, to prevent engine oscillation, and then it's applied progressively faster between 50% and wide open. The net result is smooth, controlled acceleration every time.

The acceleration limiter operates again via the EDC but using potentiometers to feed in data to the drive-by-wire throttle system. It means the driver can exploit the full power of the engine when fully laden, while limiting its when empty. In practice the bus is prevented from accelerating quicker than 1.3m/see, regardless of terrain, traffic or load. If the system detects acceleration beyond that level it simply backs off the EDC fuel pump.

In 1989 CM reckoned that such a system: "...might well ensure that the drivers of the latest generation of high-powered artics are less likely to be corrupted by the power beneath their right foot." It seems MAN took those words to heart—the 19.603 has an acceleration limiter as standard.

CM would love to tell you exactly how it works. For the past five weeks we've been chasing Munich to give us the technical lowdown on the system. However, a fortnight ago MAN told us that "We have applied for a patent concerning the electronic control of the V-10 motor. Unfortunately we cannot answer your very detailed questions."

Until that patent is granted we're pretty much in the dark —but what we do know, based on our original drive of the 19.603 back in December, is that acceleration is sensed via an accelerometer on the propshaft. And when the truck's acceleration exceeds a predetermined level, torque is limited via the vee-10's electronic fuel injection system which has a Bosch P8500 pump. The torque limiter function normally comes into action when the 19.603 is lightly laden and at lower road speeds Out on the road, the only thing the driver notices when the system operates is that the accelerator pedal reacts slower against the pressure of his foot. How engine load is sensed, or how the system communicates with other parts of the driveline, no doubt MAN will say when it the time is right.

What is clear is that with 2,700Nm (1,9911bft) of torque on tap the engineers at MAN are well aware of how the 19.603's power could corrupt. And they're clearly deter ,. mined not to let it go to the driver's head—or right foot.

U by Brian Weatherley.