Squeezing the most out of rubbish

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Grundon looked at alternative methods of disposal and decided that high-density baling is the answer. David Wilcox reports

THING Britain is still wing at a healthy rate is sh.

) millions of tons of dry — in the form of industrial iomestic household refuse in the main, still disposed much the same way as it een for years.

) council dustcarts take the ie to transfer stations, a it is loaded into bulk revehicles under slight comm. From here it is taken to infill sites such as disused

and clay pits which are ially filled in to become land for agriculture or dement.

lndon is a waste disposal any with a 100-strong fleet ) in the Thames Valley reof Berkshire, Buckinghire and Oxfordshire and een taking refuse to landfill in the usual way for more 50 years.

lough its job has remained ally the same, as time went he number of available II sites has become fewer ewer — we are filling pits than we're making them. result, the refuse is being d further and costs are Cr. To tackle this problem Grundon decided to look at alternative waste disposal methods used in Europe and the USA in 1974. Incineration and pelletisation into solid fuel were two of the methods examined, but the company eventually decided that high-density baling was the best answer.

This was a new technique in Europe and involves compacting the refuse under immense pressure into manageable bales which can then be laid in the infill site rather like laying bricks.

This has two main advantages: the transport costs are reduced because the refuse is high density, and secondly far more refuse in this very compact state can be put in the infill site so that the pit — a waste disposal operator's most valuable asset — lasts longer.

So Grundon decided to take the plunge and in fact bought the largest high-density baler of its kind in the world. Made by Lindemann of West Germany, the £600,000 machine sits in a purpose-built plant opened by Environment Secretary Michael Heseitine in October last year at Colnbrook, near Heathrow Airport.

Grundon operates the plant on a contract for Berkshire County Council disposing of trade and domestic refuse for the county. The loose refuse is brought into the plant by council's own dustcarts, Grundon's bulkers or other operators.

It is mixed using a Volvo BM shovel loader to give it an even density (domestic refuse is usually denser than trade refuse} and then scooped onto the baler's conveyor.

This carries the refuse up into the pressing part of the baler where a horizontal ram compresses it with a force of 280 tonnes. This compares with most container-type compactors which operate at around 70 tonnes.

About six to eight minutes later the refuse is ejected from the end of the baler in the form of a bale weighing four to five tonnes, already wired up to keep its shape.

Lindemann built the baler to Grundon's requirements so the size of the bale is designed to suit the internal dimensions of the vehicles' bodies. The lorry merely reverses up to the machine and the bales are pushed onto the back of the lorry, one behind the other. Rigids can carry three or four bales while artics take five. The length of the bale can be varied by the operator so that the weight/volume ratio of the bale suits different vehicle body lengths. Its virtually a continuous process through the day and handles about 60 tonnes an hour.

Grundon runs a mixed fleet of rigid tippers and artics, and although the rigids happily accepted the bales through the rear door the artics presented problems. The company first used flat trailers and so the bales had to be roped and sheeted in the normal way but they still tended to shed a little of their outer layer, spreading refuse around the site. So Grundon started using tipping semitrailers instead and these have proved far better and tidier. Because the balers are loaded via the rear doors the fly sheet always remains in place and there is no danger of the paper and other light refuse flying around the countryside that can often be seen behind poorly sheeted refuse bulkers.

Once at the landfill site the vehicles — be they rigid or artic tippers — drive onto the tipping site and tip the body. Instead of loose refuse pouring out which then has to be levelled by mechanical shovels on site, the bales gracefully slide out. The vehicle drives forward slowly, thus laying the bales side by side to give a neat, compact mull. At least, that's the theory.

Unfortunately, Grundon found that it didn't always work like this. As the bales slid off the back of the tipper body it was a fairly long drop to the ground and some of them either rolled onto their ends or, worse still, would burst on impact with the ground, leaving a row of neat bales and then an enormous pile of uncompacted refuse.

Grundon once again tackled the problem and came up with a modification to avoid this. It involved a partial, bottomhinged tailgate which would fold down level with the floor of the tipper body acting as an extension which would support the bale so that it hit the ground rather more gently.

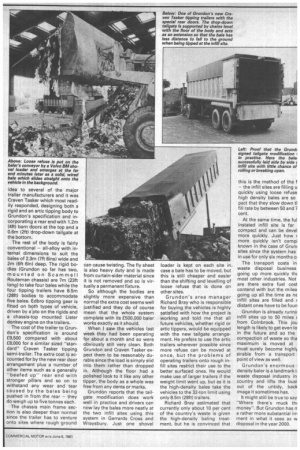

The company presented this idea to several of the major trailer manufacturers and it was Craven Tasker which most readily responded, designing both a rigid and an artic tipping body to Grundon's specification and incorporating a rear end with 1.2m (4ft) barn doors at the top and a 0.6m (2ft) drop-down tailgate at the bottom.

The rest of the body is fairly conventional — all-alloy with internal dimensions to suit the bales of 2.3m (7ft Sins) wide and 2m (6ft Sin) deep. The rigid bodies (Grundon so far has two, mounted on Scammell Routeman chassis) are 7m (23ft long) to take four bales while the four tipping trailers have 8.5m (28ft) bodies to accommodate five bales. Edbro tipping gear is fitted on both types of vehicle, driven by a'pto on the rigids and a chassis-top mounted Lister donkey engine on the trailers.

The cost of the trailer to Grundon's specification is around £9,500 compared with about £8,000 for a similar sized "standard" Craven Tasker tipping semi-trailer. The extra cost is accounted for by the new rear door arrangement plus a number of other items such as a generally "beefed up" rear end with stronger pillars and so on to withstand any wear and tear caused by the bales being pushed in from the rear — they do weigh up to five tonnes each.

The chassis main frame section is also deeper than normal since the trailer has to venture onto sites where rough ground can cause twisting. The fly sheet is also heavy duty and is made from curtain-sider material since it is not removed and so is virtually a permanent fixture.

So although the bodies are slightly more expensive than normal the extra cost seems well justified and they do of course mean that the whole system complete with its £500,000 baler works exactly as it should.

When I saw the vehicles last week they had been operating for about a month and so were obviously still very clean. Both Grundon and Craven Tasker expect them to be reasonably durable since the load is simply slid into them rather than dropped in. Although the floor had a polished look to it like any other tipper, the body as a whole was free from any dents or marks.

Grundon reports that the tailgate modification does work well in practice and drivers can now lay the bales more neatly at the two infill sites using this system in Gerrards Cross and Wraysbury. Just one shovel loader is kept on each site in. case a bale has to be moved, but this is still cheaper and easier than the shifting and levelling of loose refuse that is done on other sites.

Grundon's area manager Richard Bray who is responsible for buying the vehicles is highly satisfied with how the project is working and told me that all future vehicles, whether rigid or artic tippers, would be equipped with the new tailgate arrangement. He prefers to use the artic trailers wherever possible since more refuse can be moved at once, but the problems of operating trailers onto rough infill sites restrict their use to the better surfaced ones. He would make use of larger trailers if the weight limit went up, but as it is the high-density bales take the vehicles to the 32-ton limit using only 8.5m (28ft) trailers.

Richard Bray estimated that currently only about 10 per cent of the country's waste is given the high-density baling treatment, but he is convinced that this is the method of the f — the infill sites are filling u quickly using loose refuse high density bales are so pact that they slow down ti fill rate by between 50 and 7 cent.

At the same time, the ful instated infill site is far compact and can be devel more quickly. Just how 1 more quickly isn't compl known in the case of Grum sites since the system has in use for only six months o The transport costs in waste disposal business going up more quickly thz most other industries. Not are there extra fuel cost contend with but the milea going up all the time as n€ infill sites are filled and r distant ones have to be foun

Grundon is already runnir infill sites up to 50 miles z. from Colnbrook. This jou length is likely to get even lo in the future and so the compaction of waste so tha maximum is moved at must surely become highly sirable from a transport point of view as well.

Grundon's enormous density baler is a landmark h waste disposal industry in country and lifts the busi out of the untidy, back image it sometimes has.

It might still be true to say "Where there's muck th( money". But Grundon has a rather more substantial in' ment in what it sees as vv disposal in the year 2000.